LATEST NEWS

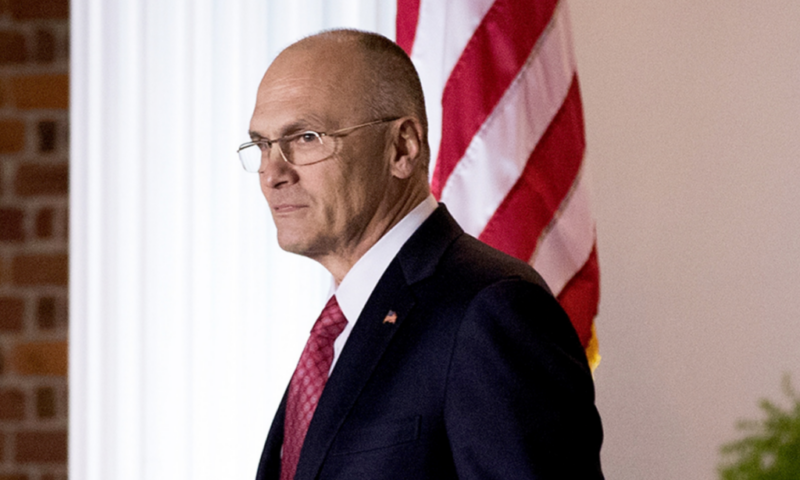

Andrew Puzder oversaw the highest rate of federal job bias claims among big burger chains.

They were young and old, women and men, black, brown and white and everyone in between. All crushed together in a crowd officially estimated at 750,000 – far larger than expected but mellow, good-natured and happy to be seen.

Capital & Main’s special series on Donald Trump’s polarizing pick to head the Department of Labor. Stories co-published by Newsweek, International Business Times, American Prospect and Fast Company

It had been so long since I’d been at a demonstration, a real demonstration – one hung on the scaffolding of sincerely determined resistance and hope — that I’d forgotten how to conduct myself.

Betsy DeVos, Donald Trump’s pick to run the Department of Education, certainly has an opinion. Despite never having taught in, managed, or attended a public school, DeVos believes that public school children should be in private hands.

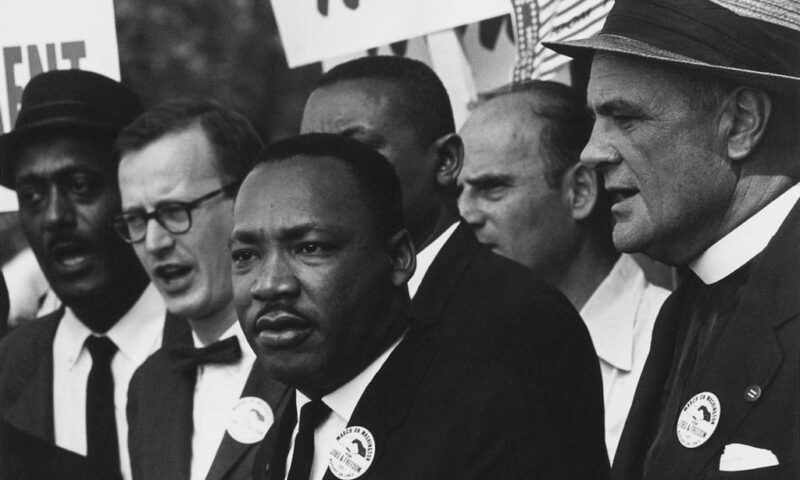

Ceremonies honoring the birth of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. began over the past weekend and culminate today. Below are three California cities that will feature extensive events.

One phrase describes how many people feel about this next chapter of the American experiment in self-rule: We fear the worst.

If you’re interested in cultivating mindfulness, equanimity and loving-kindness, see Jim Jarmusch’s new film, Paterson. The movie is about a bus driver in Paterson, New Jersey.

President-elect Donald Trump hasn’t yet sworn his oath of office, but his announced policies have already thrown a Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors meeting into pandemonium. BY LEIGHTON WOODHOUSE

These five important executive orders affecting federal contractors were issued by President Obama — will they survive a Trump administration? BY BOBBI MURRAY

She stood ramrod straight with curled gray hair, tasteful clothes and a dignified demeanor. Her look, combined with her sharp mind and renown as an American historian, could be intimidating. But Joyce Appleby, who died December 23 at the age of 87, was “always kind, always respectful.”

Candidate Donald Trump promised to “drain the swamp,” but as President-elect Trump he’s already flooding it with more of the same.

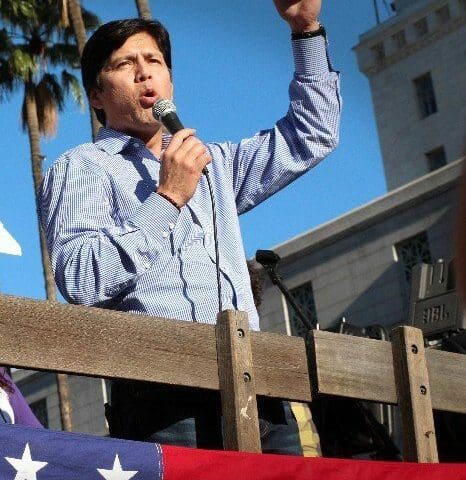

Today California legislators returned to their jobs in Sacramento, facing a new year and, for Democrats, a distressing new reality: their first session under the incoming presidency of Donald J. Trump.

Immigrant families feel fear. Children cry in school. Racial incidents increase across the country. Corporate stocks tumble following one man’s tweets. Every White House cabinet nomination becomes an occasion for dire speculation.

In a sign that California is quickly emerging as the nation’s progressive conscience-in-exile, a new Los Angeles education-reform group has launched an ambitious initiative that it claims could close historic student achievement gaps at the Los Angeles Unified School District.

Our concluding roundup of Capital & Main’s best features of 2016 includes profiles of public school teachers who drive for Uber to make ends meet and the story of one Los Angeles charter school that failed after it chose an ex-football player with no educational experience to run it. See stories in Part One and Part Two.

Today we continue our look back at Capital & Main’s best work of 2016. Stories focus on the “shared economy,” the affordable housing crisis, legalized marijuana and charter schools.

Stories that survey a California whose residents are forced to drive for Uber or live in rooms with cardboard walls.

Co-published by Reuters

What does Donald Trump have in common with animal rights activists? At face value nothing, of course. Yet both have mainstreamed positions that were until recently seen as marginal.

In the otherwise dark year of 2016, California doubled down on its faith in people and the future with major victories for labor, the environment and public education. Here are five ways the Golden State left the light on for the rest of the country.