Co-published by Fast Company

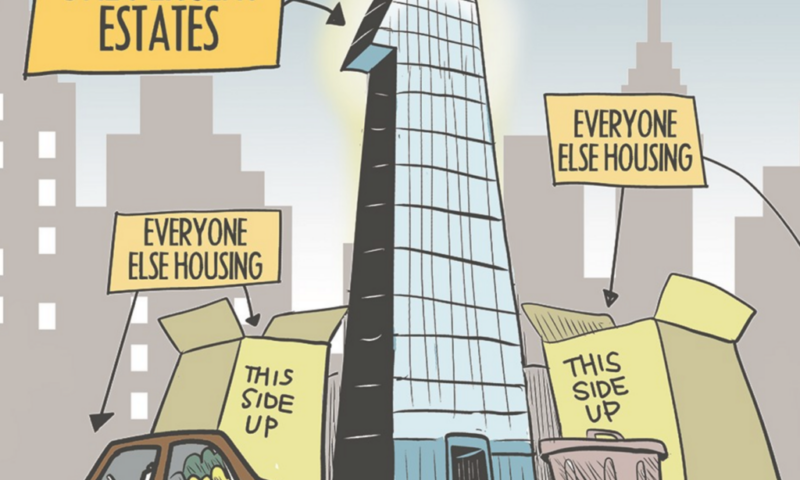

Is our budding tech utopia setting the stage for a working-people’s dystopia? Welcome to California’s cost-of-living crisis.

California’s housing shortage has made it difficult to be middle class and harder to be poor. Today’s median-priced California home costs more than twice the median-priced U.S. home, according to Zillow.

Co-published by International Business Times

In California’s recent legislative “grand compromise” of an affordable housing package, developers got subsidies for building and a streamlined path to construction. It’s hard to see what they gave up in the exchange.

Co-published by The American Prospect

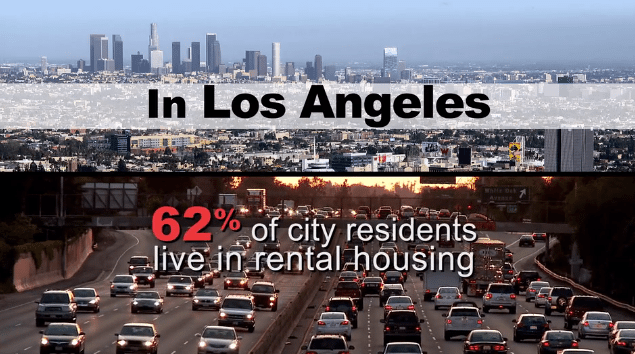

California’s red-hot housing market has made renters vulnerable to rapidly increasing rents that they struggle to pay, or to evictions implemented by landlords who want to raise the rent on new tenants.

California’s housing predicament has been at critical mass for a long time – on any given night there are 47,000 homeless people living on L.A. County streets.

Rarely has a ballot measure united so many divergent groups in opposition as has Measure S, a proposition on the city’s March 7 ballot that would impose strict limits on development.

Sasha Abramsky: Why hopes are riding on the Build Better LA Initiative.

In Santa Monica a group of residents – frustrated by traffic and angry at developers – has placed a no-growth measure on the local ballot. It would force nearly all new projects higher than 32 feet to a citywide vote. The backers of Measure LV say that it’s buildings of all kinds – whether they house people or create jobs – that bring choking traffic.

The shortage of affordable rental housing can be traced directly to the 1980s when the federal government sharply curtailed domestic spending.

The way Esther Delahey sees it, her neighborhood in south Fresno, the Lowell district, has gotten a bad rap. Named in 1884 for the New England poet James Russell Lowell, the district is part of a larger area, hemmed in by three highways.

California leads the nation in having the most severely rent-burdened households, as well as having the largest shortage of affordable rental homes. (The U.S. Department Housing and Urban Development and other agencies consider families that spend more than 30 percent of their income on rent as rent-burdened.)

Isabelle Lopez, her husband and their dog live in a tiny room, perhaps 130 square feet, in the impoverished Lacy neighborhood in the Orange County city of Santa Ana.

Housing developers – whether they specialize in market-rate properties or affordable housing – face tremendous hurdles in getting projects off the ground in California.

“There’s probably a hundred challenges,” says Cynthia Parker, the president and chief executive officer of BRIDGE Housing, a nonprofit housing developer based in San Francisco.

See More Stories in Capital & Main’s Affordable Housing Series

Material prices keep going up, with the costs of steel and glass not expected to come down any time soon. Labor expenses also keep rising. Even with the lowest interest rates in our lifetime, it still can be very difficult to make economic sense for starting a new construction project without some sort of guarantee that it will not be a bust. Developers say that perhaps the toughest impediment to new housing construction is local opposition, especially if the proposed construction site is in a safe neighborhood with good schools.

» Read more about: The Developer’s Story: Why Affordable Housing Doesn’t Get Built »

Grade-school art teacher Melissa Jones is attending the opening of an exhibit called Roofless: Art Against Displacement at the Arlene Francis Center in Santa Rosa. It is a cold, rainy night in early January. Jones is a single mother; she and her 12-year-old son live in a one-bedroom basement flat in the nearby rural community of Forestville, for which she pays $825 per month plus utilities. She is desperate to move into a bigger place, but for many the rents in Sonoma County have become unaffordable.

See More Stories in Capital & Main’s Affordable Housing Series

Among other problems, too few apartment buildings have been built in recent years. Developers say they have been hampered by huge impact fees that can run as high as $100,000 a unit, that cash-strapped localities in California, operating in a tax-raising environment straitjacketed by Proposition 13, have imposed on builders. The collapse of redevelopment funding has further reduced local governments’ ability to build enough subsidized housing.

It’s no secret that California residents pay more for housing than residents in most other states, especially in the metropolitan coastal areas and Silicon Valley cities. Los Angeles, San Diego, San Francisco, San Jose, Palo Alto and other highly attractive, jobs- and amenities-rich cities are widely documented as being the least-affordable housing markets in California.

See More Stories in Capital & Main’s Affordable Housing Series

Obtaining decent affordable rental housing and earning enough income to sustain a family are increasingly more difficult goals to achieve. The American Dream of homeownership, and of building and maintaining stable communities, is fading in the face of this new socio-economic reality.

Red flags abound: The state’s poorest families pay up to two-thirds of their income on housing, firmly placing them in the severely “rent burdened” category of households. (Families that spend more than 30 percent of their income on rent are considered rent-burdened by the U.S.

» Read more about: Trouble on the Dream Coast: Housing Policy Challenges »

One block north of fabled Hollywood Boulevard, and a stone’s throw from the iconic Capitol Records Building, sit three rent-stabilized, two-story apartment buildings, known to residents as the Yucca-Argyle complex. One building is peach-colored, one green and the third yellow. Each is organized around a small courtyard and in back is a parking lot for tenants’ cars. Together they are home to roughly 50 families, the residents ranging in age from young children to old-timers who have lived in the complex for more than half a century.

See More Stories in Capital & Main’s Affordable Housing Series

By most measures the complex’s residents have it good. Living in one of L.A.’s more walkable and vibrant neighborhoods — where cafes, bookstores, night clubs, restaurants and clothing boutiques vie for consumers’ attention — they pay varying amounts above $1,000 for a one-bedroom apartment, beneficiaries of Los Angeles’s 1978 Rent Stabilization Ordinance (RSO).

» Read more about: Renting in Los Angeles — Dislocation, Dislocation, Dislocation »

Photojournalist Ted Soqui shot these images for today’s story by Sasha Abramsky, Renting in Los Angeles — Dislocation, Dislocation, Dislocation.

See More Stories in Capital & Main’s Affordable Housing Series

California’s housing crisis is a complex one, as befits a state with a population of close to 40 million people, spread out over 163,696 square miles, and with some of the country’s largest cities and fastest growing population hubs, as well as some of its most rugged rural areas.

See More Stories in Capital & Main’s Affordable Housing Series

Los Angeles’ Skid Row sprawls just a few blocks from the skyscrapers of downtown and showcases one of the developed world’s largest concentrations of long-term homeless people. They live in tents and jerry-rigged shanties along the sidewalks and in vacant lots, surround social service agency buildings and provide a vista of misery stunning in its intensity. Only a few miles away, middle- and working-class tenants are being driven from their rent-controlled homes into the exurbs or onto friends’ and relatives’ couches. The causes of this diaspora are developers seeking to capitalize on Hollywood’s soaring real estate values and the city’s “densification” development strategy that prioritizes large-scale,

» Read more about: Affordable Housing: Introduction to a Crisis »

“No Direction Home” reaches many troubling conclusions about California’s housing market