Labor & Economy

Affordable Housing: Introduction to a Crisis

California’s housing crisis is a complex one, as befits a state with a population of close to 40 million people, spread out over 163,696 square miles, and with some of the country’s largest cities and fastest growing population hubs, as well as some of its most rugged rural areas.

See More Stories in Capital & Main’s Affordable Housing Series

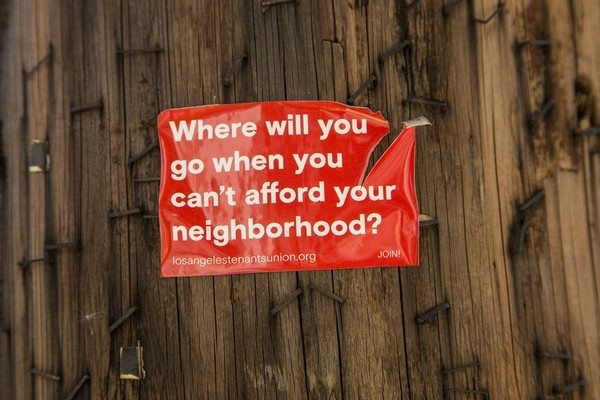

Los Angeles’ Skid Row sprawls just a few blocks from the skyscrapers of downtown and showcases one of the developed world’s largest concentrations of long-term homeless people. They live in tents and jerry-rigged shanties along the sidewalks and in vacant lots, surround social service agency buildings and provide a vista of misery stunning in its intensity. Only a few miles away, middle- and working-class tenants are being driven from their rent-controlled homes into the exurbs or onto friends’ and relatives’ couches. The causes of this diaspora are developers seeking to capitalize on Hollywood’s soaring real estate values and the city’s “densification” development strategy that prioritizes large-scale, high-end housing developments over new affordable housing for middle-income families and the working poor.

The extremes of poverty and affluence do a strange dance in L.A.’s housing story, as they do in San Francisco to the north.

Says tenants’ organizer Dont Rhine, a Hollywood-based artist who cut his teeth in the world of activism working for ACT UP in the 1990s, “There are a lot of renters who are frickin’ pissed off. I’ve not seen anything like this since the AIDS crisis. It’s affecting mental health and physical health.”

By contrast, in the Central Valley deep pools of poverty in cities such as Fresno — the core of which has the third highest poverty rate of any large metro area in the country — perpetuate the existence of slum housing. Twenty years ago, in a deal that then-President Bill Clinton carved out with a conservative Congress, the country’s political leadership eliminated 100,000 units of public housing. Years later, in 2011, the California legislature, at the urging of Governor Jerry Brown, scrapped a program that had funneled billions of dollars from the state into local redevelopment agency grants. Today, while Fresno’s Housing Authority and nonprofit homebuilders such as Self Help Enterprises try to provide decent, affordable housing for the lucky few, the need massively outstrips the supply. Tens of thousands of families are poor enough to qualify for housing vouchers, affordable housing in mixed-income units or public housing, yet most will never be provided an apartment or house.

Roughly 67,000 families in the Fresno area are on waiting lists for these programs. With each year, as federal investments in housing lag, the problem gets worse. Making the matter ever more urgent is the fact that it is in Central Valley towns that much of California’s population growth in coming years is predicted to occur. Absent huge investments in affordable housing, a growing number of Californians in the valley a generation from now will be living in slums, at the mercy of a private rental market utterly indifferent to their basic needs and dignity.

In Orange County, widespread affluence has pushed up real estate values beyond anything affordable to the low-wage, service-sector workers, many of them undocumented, who cater to affluent residents’ consumption needs. As a result, with years-long waiting lists for Section 8 vouchers (for qualified recipients who pay up to 30 percent of their income on rent, with the difference, up to a certain rent threshold, paid for by the government); with a paucity of affordable housing units being built; and with vast shortages in public housing, many residents double, triple or quadruple up, creating some of the most overcrowded and unhealthy living conditions in America.

“Where should I go with no job?” asks Santa Ana resident Concepcion, an undocumented immigrant who has run through her legal options and is at risk of imminent deportation. She lives with her husband and three children inside a tiny room within a small house, in a poor part of town. Recently, a teenager living near the house drew a gun on a police officer and, to Concepcion’s horror, she saw heavily armed SWAT teams swarm past her window. “Low-income housing?” she asks. “I’m ineligible. It’s either here or under a bridge or the public library, where the homeless are.”

It’s a choice many Santa Anans have had to make. When the city surveyed the transient population recently, it found more than 400 people living on the streets surrounding Civic Center Plaza – and another 400-plus living along the Santa Ana riverbed. There are, according to Judson Brown, the housing division manager for the city’s Community Development Agency, only 185 shelter beds for the homeless in Santa Ana and, of these, nearly three quarters are only available during the cold winter months.

In the Bay Area one town after another has witnessed spiraling real estate dislocations as San Francisco’s soaring property market continues to create spillover effects in neighboring counties. In the city itself, family apartments in traditionally immigrant and working-class neighborhoods such as the Mission District have been converted into million-dollar pads for young techies, an ongoing problem driven by the presence of many of the world’s top tech companies in Silicon Valley just a few miles to the south.

Across the bay in Oakland, gritty neighborhoods in that city’s west and north are rapidly being gentrified; there’s some good to this – in lower crime rates and more vibrant economic activity – but also a lot of bad. Historically African American and Latino areas are bought into by a wave of disproportionately white and Asian-American gentrifiers, as they and investors snap up any and all properties that come onto the market. Existing residents find that they can no longer afford exploding rents and are pushed ever further from their places of work and the schools that their children are enrolled in. People with precious few resources to begin with are uprooted and, in essence, told to start afresh.

As a domino line of towns is hit by the Bay Area real estate boom’s shockwaves, so the dislocation spreads further afield. In the last few months, long-time working-class residents in Redwood City and other cities in the vicinity have almost overnight been swept aside by a tsunami of real estate investors taking advantage of their proximity both to Silicon Valley and to San Francisco. Absent a coherent affordable housing development strategy in these towns, local housing activists fear that low- and moderate-income families will no longer be able to stay in the city.

This series is the story of California’s housing crisis, a crisis that shows no sign of abating. We have decided not to focus on long-term homelessness here, because it is a complex saga involving a discussion of mental health services, addiction treatment and the ways in which foster care kids, veterans and ex-prisoners are too often cast aside by the broader society, that merits a later series unto itself.

Instead, in this series we will mostly look at those who have roofs over their heads, but whose situations are increasingly precarious.

The affordable housing crisis did not occur in a vacuum, but has its roots in both the last recession and in laws written years before that tilted California’s housing relationships in favor of landlords and developers. When the housing market collapsed eight years ago, it was homeowners who bore the brunt of the calamity, with entire neighborhoods destroyed by foreclosures. Today, with California’s real estate market rebounding, owners are again accumulating paper wealth. Increasingly, as property values soar, especially in thriving coastal cities, it is renters who now bear the greatest pain.

As mentioned, Governor Brown’s scrapping of California’s redevelopment agency program — a response taken against the state’s post-2008 financial crisis — deprived local housing budgets of hundreds of millions of dollars overnight. Not surprisingly, as more people find themselves priced out of quality housing, they are bumping up against the realities of catastrophic under-investment in decent affordable housing — a situation in which slum landlords are filling the void.

Renters are also confronting California’s Ellis Act, which provides a mechanism whereby property owners can evict rent-controlled tenants, demolish homes and rebuild the properties as upmarket homes. And they are grappling with the state’s Costa-Hawkins Act, pushed in the 1990s by many of the same conservative political lobbies that propelled Proposition 13 to victory in 1978, and which forbids cities to rent-stabilize properties built after 1995. How bad is the housing crisis in California? Last year the chair of the state agency responsible for programs that create affordable housing stepped down under pressure when activists revealed he was evicting tenants from property he owned in order to replace its rent-controlled units with luxury ones.

In the coming days we will tell the tale of the struggling middle class and working poor in an era in which public investments in affordable housing have shamefully lagged, and in which politicians have too often catered to the needs of developers rather than to those of renters and lower income homeowners.

We will also explore the economic and health implications of substandard slum housing; the policy implications of growing wage inequalities in a high-cost real estate environment; and the dangers to the social fabric posed by the recreation of housing conditions that would have been all too familiar to Jacob Riis, the social reformer who photographed New York’s slums more than a century ago.

Tuesday — Los Angeles: Dislocation, Dislocation, Dislocation

-

The SlickJanuary 27, 2026

The SlickJanuary 27, 2026The One Big Beautiful Prediction: The Energy Transition Is Still Alive

-

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 29, 2026

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 29, 2026Are California’s Billionaires Crying Wolf?

-

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026Amid the Violent Minnesota Raids, ICE Arrests Over 100 Refugees, Ships Many to Texas

-

Dirty MoneyJanuary 30, 2026

Dirty MoneyJanuary 30, 2026Amid Climate Crisis, Insurers’ Increased Use of AI Raises Concern For Policyholders

-

Featured VideoFebruary 4, 2026

Featured VideoFebruary 4, 2026Protesters Turn to Economic Disruption to Fight ICE

-

The SlickFebruary 2, 2026

The SlickFebruary 2, 2026Colorado May Ask Big Oil to Leave Millions of Dollars in the Ground

-

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 5, 2026

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 5, 2026Lawsuits Push Back on Trump’s Attack on Child Care

-

Column - California UncoveredFebruary 6, 2026

Column - California UncoveredFebruary 6, 2026What It’s Like On the Front Line as Health Care Cuts Start to Hit