Just about every day we hear about how consumer spending is the main driver of the economy. If only we’d spend more money, we could get the economy back on track. (Of course, this is overly simplistic, and fails to account for any number of factors, not least being the continued drag of housing on the economy, as well as the mountains of cash that businesses are sitting on as they fail to hire workers.)

So I’m doing my part—in fact more than my part.

You see, in a few days, I’m getting married. I never would have imagined the amount of money that my wedding is plowing into our local economy: thousands of dollars to a caterer, a bartending service, an equipment rental outfit, a DJ. We’re renting a municipally-owned venue, so the City should be getting a taste,

There’s something eerily Orwellian about the recent blog post, by L.A. Area Chamber of Commerce president Gary Toebben, entitled “L.A. Should Vote Down New Bureaucracy to Regulate Banks.” Mr. Toebben claims that a proposed new city ordinance that would reward banks that act responsibly toward L.A. consumers with the city’s deposits is “overly burdensome” and an “unnecessary regulation.” This is because, Mr. Toebben argues, “the federal government oversees a heavily regulated banking industry” — implying that businesses like banks and other job creators need to be left free to make lots of money, create lots of jobs so that the benefits can trickle down to everyone else.

Say what?

The banking industry in the United States is “heavily regulated?” Really? Did the L.A. chamber somehow miss the great recession of 2008? You know, that one where the under-regulated banks got into so much trouble that we had to spend more than $700 billion in taxpayer money to bail them out?

» Read more about: The Chamber of Commerce’s Orwellian Position »

We know Los Angeles is in dire need of both jobs and a transportation system that works. Recently, the Metro Board of Directors took action by moving forward on a sweeping, agency-wide Construction Careers Policy covering Metro construction projects for the next 30 years, including projects funded under Measure R, the half-cent sales tax.

The vote at Metro was preceded by more than a year of hard work by LAANE, the L.A./O.C. Building Trades Council, and a coalition of community, environmental, labor, and transportation advocates – all united to make sure that our tax dollars are used to make Los Angeles a working, greener city. This policy brings together the taxpayers’ wishes for better public transportation and our critical need to get Americans back to work.

Anthony Mitchell, an electrician and single father of two whose family is facing foreclosure, attended the vote.

As reported in a leading New York business paper, “the National Taxi Workers Alliance, which is not formally a union, is the first non-traditional labor organization to join the AFL-CIO since a farm workers group was chartered in the early 1960s.” This is exciting news for a few reasons: first, because it illustrates that labor leaders are thinking more creatively about how to reach hard-to-reach workers, and also because it shows how those organic worker organizations are getting formal institutional support. This is a good thing for both sides.

Beyond this, as the AFL-CIO blog entry describes, these are marginalized workers, workers who have historically been deprived of their legal rights because they have been misclassified as independent contractors. This is a problem we have seen again and again, and which we have visited before on the Frying Pan. As employers continue to push the envelope with these legal shenanigans,

» Read more about: Interweb Special: Taxi Alliance Joins AFL-CIO »

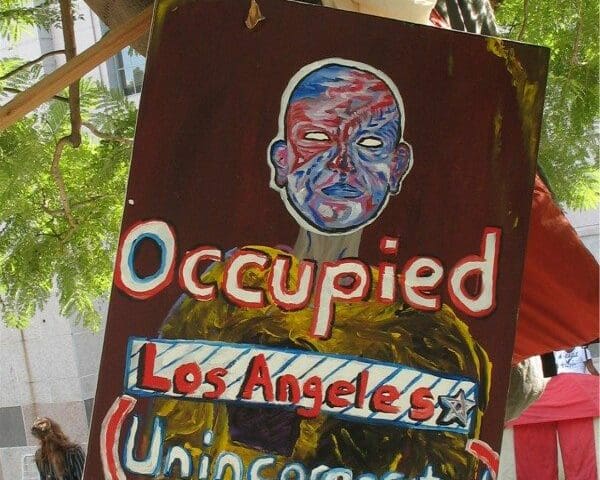

What would cause 13 mostly 30- and 40-something electricians to come up with an event like the “Solidarity Sleepover” at Occupy LA? It all started with a text message. Howard Brown, adventurer, electrician and Occupy LA supporter wrote me, “would like 2 c mas union presence.” I had not been down to Occupy LA and before I put my name near it, I needed to do some recon to check it out. I had heard that it was this leaderless movement that really had no strong positions on anything because they could not get a consensus from the group. Being a lifelong Democrat, that sounded vaguely familiar. So down to City Hall I went with my good friend Gary in tow. I figured I needed some backup in case somebody tried to put a red Che Guevara beret on me when I wasn’t looking.

What Gary and I found instead were really cool,

» Read more about: What the Hell Is a Solidarity Sleepover? »

The great journalist Lincoln Steffens visited the USSR shortly after the Russian Revolution and infamously declared that he had “seen the future and it works.” My wife Mickey and I recently returned from a touristic trip to Norway, Sweden and Denmark. Most of our time was spent in typically touristic ways, but inescapably (and with help from our excellent tour guides) we got a taste of policy and politics in the current Scandinavian way. What we learned makes me want to say that we saw one future that seems to be working.

Norway is still responding to the horrifying July 22 terrorist massacre—but Norwegians are likely to say, as did Prime Minister Jens Stoltenberg: “You will not destroy our democracy or our commitment to a better world. We are a small but proud nation . . . but no one will ever frighten us away from being Norway . . . the answer to violence is even more democracy,

» Read more about: Fjord Foundation: Norway’s Solid Safety Net »

The L.A. Times had two interesting pieces on college football this last season. The second (don’t worry, I’ll get to the first), is an editorial calling on the NCAA to reform the sport by improving conditions for the so-called amateurs who generate millions of dollars every Saturday.

The piece calls for some sensible and straight-forward steps, largely echoing the basic demands of the National College Players Association, a project sponsored by the United Steelworkers.

Its heart, however, comes from a fantastic piece in The Atlantic by Taylor Branch, best known for his trilogy of books about the civil rights movement; if you haven’t read them, your life is incomplete. That gives him a certain moral authority in describing what he calls “The Shame of College Sports.” Go read this piece. It’s long, but worth it.

Okay, it’s long,

Confession time: I went to Arizona. Mea Culpa. I know I signed a pledge that I wouldn’t go there because of their anti-immigration laws, but then I got a call from my cousin asking us to join a family reunion in the mountains above Phoenix, so we went.

My wife Susan and I took the long way. We went through Flagstaff. Several years ago when we regularly drove to a retreat center in northern New Mexico, we discovered the cheap motels east of downtown, along old Route 66, across the road from train tracks that run 50 – 60 trains a day out of L.A. to the Midwest and back.

So we retraced our steps in Flagstaff and looked for one of our old motels. Except that when found, they looked worse for the wear. We tried to check into one but the manager just laughed at us, and handed us a key to look things over.

» Read more about: Great Divides: How the Other Thirds Live »

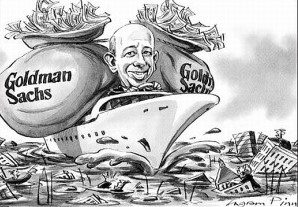

What’s fueling the ire behind the Occupy Wall Street protests that have spread from Manhattan’s financial district to cities in every state of the country and around the world? For starters, a certain corporation that 99 percent of us bailed out received $23 billion from the government but only paid one percent of its 2008 income in taxes after raking in $2.3 billion in profit.

And a new Salon.com story by Andrew Leonard, “Employers’ New Ruse: ‘Independent Contracting,” may help expose another master scheme in which Lloyd Blankfein and Goldman Sachs’ tax-avoidance maneuvering runs amok, only this time, the industry they’re manipulating isn’t banking – it’s global shipping transportation and the tens of thousands of port truck drivers that keep our economy moving.

Salon.com tells the story of Leonardo Mejia, a truck driver for Shipper’s Transport Express, a subsidiary of the massive container terminal operator SSA Marine.

I hung up the phone and got queasy. Leigh Shelton, the press spokesperson for Local 11 had just asked me if I wanted to MC the rally after the protest at the Hotel Bel-Air on Stone Canyon Road. I’m a dues -paying member of Unite Here, the hospitality workers union, but I never thought I’d be asked to do something like this.

My natural response to doing things that scare me is to say No, and then to inform the person that I would not be the right one for the job, that indeed I might be terrible. My excuse for not wanting to do this was imbedded in a traumatic comedy club experience where I thought I would give the MC position a chance. I can still see a few heckling faces in the audience to this day.

However, Leigh convinced me that it would just involve a few talking points and introducing a few key people.

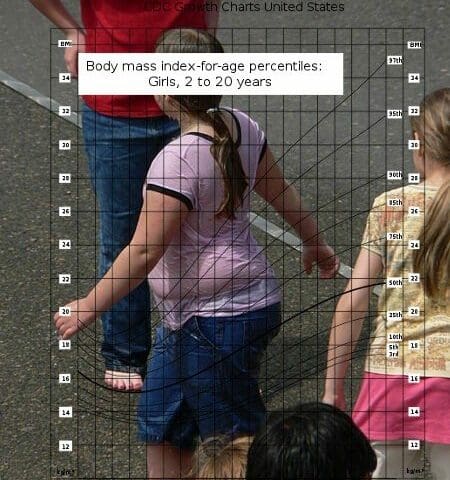

An apple a day and eating your peas led to good health, we once thought. Now, according to major food manufacturers, fruits and vegetables are “job killers” that will devastate the American economy.

In April of this year, the Federal Trade Commission, along with three other Federal agencies (FDA, CDC and USDA), released a set of proposed guidelines for marketing food to children to reduce sugars, fats and salts in the diets of American youth, and increase fruits, whole grains and vegetables. In 2008 Congress, led by Senators Sam Brownback (R-KS) and Tom Harkin (D-IA), asked for these recommendations to address the nations’ growing childhood obesity crisis.

A coalition of major manufacturers of processed foods (including Fruit Loops, Lucky Charms and SpaghettiOs), fast-food chains and the media industry that depends on their advertising dollars are spending millions on lobbyists to derail the proposed voluntary guidelines.

My dog sitter, Lezle Stein, is on fire. Let me be more precise. Lezle is a dog trainer, a shelter volunteer, animal advocate and a small business owner. She’s one of many who have been dealt a blow by this so-called recovery. When I drop off my whippet in the morning, we often check in. Lately, it’s been gloomy. There’s not been a class in weeks for Lezle to teach. She’s digging into her retirement savings. She’s looking for work to supplement her business income.

Suddenly, a week or two ago, she got a new lease on life. She had discovered Occupy L.A.. Her Facebook page lit up. She was watching movies about the labor movement. “I’m going to invite you to a meeting,” she warned one evening when I called to make arrangements for a dog drop-off.

So I went down to L.A. City Hall last Thursday to see what it was all about.

David Shoemaker, writing as The Masked Man on the sports site Grantland, describes a recent storyline on the professional wrestling TV show Raw, in which wrestlers and other employees walked off the job. The Masked Man sets off the fictional labor uprising against the actual – and unsurprisingly colorful – history of labor grievances in professional wrestling.

In one instance, wrestler and future Minnesota governor Jesse “The Body” Ventura attempted to organize a union, though he got little traction among fellow wrestlers. It was later revealed that Hulk Hogan had ratted him out to Vince McMahon. Ventura later won a significant lawsuit against his employers.

More recently, the Masked Man writes, “In 2008, three wrestlers — Raven, Chris Kanyon, and Mike Sanders — sued WWE for ‘cheating them out of health care and other benefits’ and insisted that the ‘independent contractor’ designation was a sham since WWE had ‘virtually complete dominion and control over its wrestlers.’”

The sham “independent contractor” designation is a serious issue for workers in more than a few industries.

At this very moment, Los Angeles has no professional football team and hasn’t since the Raiders and Rams both left in 1995. No club in the NFL has publicly acknowledged that it would consider moving here, although there’s always talk. Yet the Anschutz Entertainment Group has an ambitious project vying to be the home of a future Los Angeles football team, one that the city itself should push to have a stake in.

Rumors of an L.A. move have ballooned over the past year. Specifically, the San Diego Chargers have emerged as the most likely NFL team to move here, where they played their first season in 1960. They currently have a year-to-year lease at Qualcomm Stadium, which flooded last December. Their new stadium would be AEG’s yet-to-be-built Farmers Field in downtown, a large, open venue with a sleek design and a retractable roof. The economics are big, too. It is projected to hire between 20,000 and 30,000 people,

As I parked the car near the Gudiel family house on Proctor Avenue, in an unincorporated part of the San Gabriel Valley, I suddenly remembered that I forgot to tell my wife that there was a possibility that I could be arrested on this day. She’s gotten used to my activism as of late, but I suppose the wise thing to do would’ve been to ask her to keep her phone close by.

It was my first sit-in of any kind, and the first thing I noticed upon entering the side entrance was a crude set of tents propped up in the front yard that friends, neighbors and union activists had put up for a round-the-clock vigil. Spot, the family dog, greeted me at the gate with a fast wagging tail.

Due to my negligence of laundry for the past week, I was a bit overdressed, and received suspicious looks from the 8 to10 people clustered at the front door.

On Tuesday the Occupy L.A. encampment on City Hall’s narrow north lawn along Temple St. entered its fourth day. The camp first arose on the large commons on the hall’s First St. side, but like nearly all things in the city had to give way to the filming of a movie. That film, Gangster Squad, is about racket busters in the Los Angeles of the 1940s and ’50s, an era with almost nothing in common with the present city – except its growing popular dissatisfaction with the direction of the economy.

Some of the hundred or so participants this late, gray afternoon stood on sidewalks with signs (“Restore Glass-Steagall”), while engaging passersby – some from the Conrad Murray trial up the block — or taking the salute of car drivers honking their horns. Others debated among themselves on the lawn, while some kicked back in their small nylon tents.

The front page of the L.A. Times recently had a story about some hip restaurants replacing serving staff with iPads. First of all, L.A. Times: front page above the fold? Really?

Now, let’s set aside what the latest twist in automation says about us and our social interactions with other human beings. Instead, I want to focus on the fairly obvious economic implications. With apologies to Martin Niemöller:

First, they came for the bank tellers, and I said nothing, for I was not a bank teller.

Then they came for the travel agents, and I said nothing, for I was not a travel agent.

Then they came for the supermarket cashiers, and I said nothing, for I was not a supermarket cashier.

Then they came for the food service workers,

I was recently asked to take part in a “role play” for a group of Hyatt hotel housekeepers in the basement of their union hall, in the Pico Union neighborhood of Los Angeles. Each had taken a leave of absence from work to talk with community leaders about conditions for room attendants in their hotels, and they needed a chance to practice. The women belong to UNITE HERE Local 11, and are part of a national campaign of housekeepers reaching out for community support of boycotts at several Hyatt properties.

Even though some of them knew me as an active supporter of hotel workers, first as a community volunteer and then as part of the LAANE staff, I agreed to play the director of an environmental organization with limited knowledge about the hotel industry. (This last part didn’t require much acting from me.)

Sometimes struggling to express themselves in English,

» Read more about: Hotel Hell: Can Hyatt Housekeepers Win Respect? »

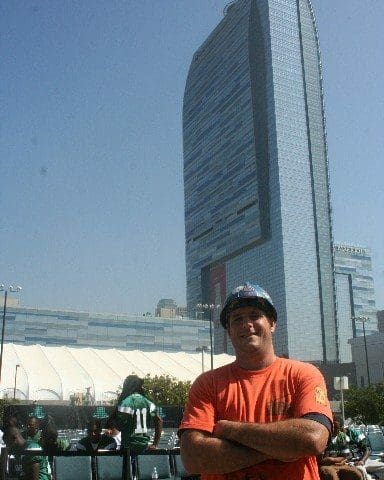

I’ve met more guys in the building trades that raise kids on their own than anywhere else in my life. That’s how I knew it was possible to do. I’m a single dad and I have primary custody of my son, Ayden. I wouldn’t have been able to do it without the stability I got from working on the L.A. Live project.

Ayden is seven now. He just started second grade. Every day after school, I help him with his spelling and sentences. We do flashcards and memory games. I have him write down a daily paragraph from Kermit the Frog’s song, “It Ain’t Easy Being Green.”

I’ve been out-of-work as an ironworker for over a year — L.A. Live was the last long-term job I had. When I worked on the project, Ayden and I lived in Long Beach. I didn’t drive and took the Blue Line every day to the Staples Center When you work construction,

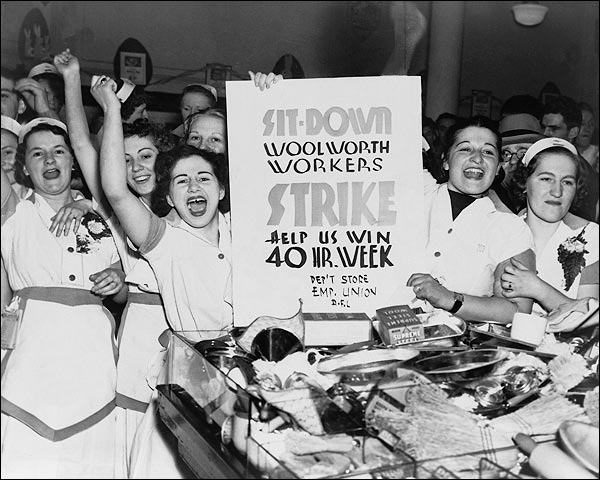

The American labor movement needs a jolt and Joe Burns’ new book, Reviving the Strike, delivers just the right shock treatment.

Debunking commonly held assumptions about labor’s inevitable decline and extinction, Burns, a veteran union lawyer, argues clearly and persuasively that worker power is still possible — but will require a dramatic shift in thinking and strategy.

Don’t expect standard academic or progressive bromides about “coalition-building,” “corporate campaigns,” “organizing-to-scale” or “social unionism.” In taking on some of the labor left’s sacred cows — living wage campaigns, worker centers, etc. — Burns praises and honors the commitment, brains and tenacity of activists. But these approaches, he suggests, lack the singular component necessary to transform power relations in the political economy. That, he contends, is the capacity to stop production.

Burns makes his case in a tightly-written narrative. After the union insurgencies of the 1930s, Congress and the courts imposed a system he calls “labor control,” one designed to disable unions’ principal and primary weapon: the strike.