David Shoemaker, writing as The Masked Man on the sports site Grantland, describes a recent storyline on the professional wrestling TV show Raw, in which wrestlers and other employees walked off the job. The Masked Man sets off the fictional labor uprising against the actual – and unsurprisingly colorful – history of labor grievances in professional wrestling.

In one instance, wrestler and future Minnesota governor Jesse “The Body” Ventura attempted to organize a union, though he got little traction among fellow wrestlers. It was later revealed that Hulk Hogan had ratted him out to Vince McMahon. Ventura later won a significant lawsuit against his employers.

More recently, the Masked Man writes, “In 2008, three wrestlers — Raven, Chris Kanyon, and Mike Sanders — sued WWE for ‘cheating them out of health care and other benefits’ and insisted that the ‘independent contractor’ designation was a sham since WWE had ‘virtually complete dominion and control over its wrestlers.’”

The sham “independent contractor” designation is a serious issue for workers in more than a few industries.

(Editor’s Note: The Help, a Hollywood film set in the Deep South during the civil rights struggle, recently scored box office gold. It seemed a rare moment in which social activism was successfully married to commerce. But was historical accuracy sacrificed for popularity – especially to reach white audiences? Two veteran political activists discuss The Help and put it in context. Today Peter Dreier compares this movie with the lesser known The Long Walk Home. Tomorrow: Vivian Rothstein, who participated in the Mississippi Freedom Summer, offers another view of The Help.)

Film director Tate Taylor scored a late-summer box office smash with his adaptation of Kathryn Stockett’s novel, The Help. A surprise hit with movie critics, too, The Help is set during the racial battles of 1963. It focuses on the efforts of African American maids to maintain their dignity despite the routine discrimination and vicious slights they confront while living in segregated Jackson,

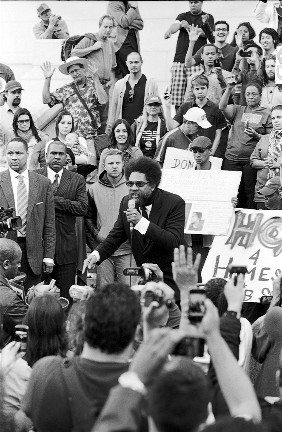

As Occupy Wall Street approaches its one-month anniversary, protest zones have been spontaneously set up from Los Angeles to Washington, D.C. Familiar bylines in America’s newspapers and on its blogs have, accordingly, been trying to explain the events.

1. The New Yorker’s Hendrik Hertzberg tries, in this week’s Talk of the Town opener (“A Walk in the Park”), not to sound too much taken in by the spirit of the protest, while at the same time acknowledging the charm of its spontaneity: “They’re making it up on the fly. They don’t really know where it will take them, and they like it that way. Occupy Wall Street is a political project, but it is equally a cri de coeur, an exercise in constructive group dynamics, a release from isolation, resignation, and futility. The process, not the platform, is the point. Anyway, [it] is not the Brookings Institution.”

Whew!

Oh, the 1960s!

Back then I was one of those middle-class married women who never dreamed of a career. Then came Betty Friedan and The Feminine Mystique. And so in my early 40s, I enrolled in the University of Pittsburgh’s School of Social Work master’s degree program.

On the very first day of class my professor wrote on the blackboard, “Social workers believe in ambivalence.” I was home. I had always been uncomfortable with unalterable truths — generalized philosophies and rules and theories that were supposed to apply across time, place and circumstances.

Now that, 50 years later, there is so much attention being paid to aging (and it’s me the experts are referring to in their speculations), I’ve become weary of all the guarantees being offered for a healthy, long — and I do mean long — happy life.

Ten members of the Irvine 11 were sentenced last week to community service, fines and probation for disrupting a speech by the Israeli ambassador on the campus of UC Irvine. It’s not as important to me whether or not these Muslim activists were within their rights under the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution as that they were ready to take the risk that civil disobedience implies for their strongly held beliefs.

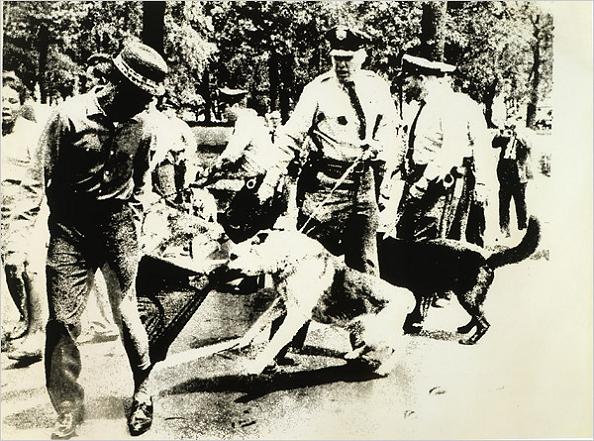

As a veteran of the 1960s civil rights movement, I know how breaking a law in pursuit of a higher justice can be a life-changing experience. When I was 18 I joined 400 others protesting discriminatory hiring practices at a San Francisco auto dealership by going limp in the car showrooms.

The status quo does not change without pressure from below. And in the U.S. often that pressure has taken the form of several hundred people “putting their bodies on the line” —

Ernest Melendrez, like many others who work for nonprofit organizations, is passionate about his job. The long hours, modest pay and oftentimes emotionally trying work require the deepest level of commitment. His passion for the work he does at Friends Outside, a nonprofit focused on prisoner reentry, comes from his own life experience. From the time he turned eight, Ernest found himself in and out of the juvenile and corrections systems in California and Arizona. By his final reentry into the “outside” in 2007, Ernest had made up his mind: He was ready to live. At only 35 he still had a lot of life to experience outside the walls of San Quentin and Folsom.

I sat down with Ernest last week to talk about his life both in and out of incarceration. As part of California’s prisoner re-alignment program, California’s 58 county jail systems will gradually begin housing and supervising thousands of nonviolent criminals and parole violators due to overcrowding in state prisons.

Zoos are complex places — literally. Each time I enter one, I’m filled with a nagging ambivalence between competing views and emotions. On one hand, I think about the animals forced to live in enclosed compounds far from their natural setting. But on the other hand, I’m filled with childlike awe and wonder as I watch gorillas, elephants, hippos and the many bird, amphibian, reptilian and mammalian specials that I’d never even heard of.

Zoos have made real progress in how they treat their captives. It’s no longer standard practice – as it was in the zoo of my youth – to keep the animals in small oppressive cages. Today, zoo enclosures mimic natural animal habitats. They’re bigger and have corners and caves where animals can hide from the crowds

So, I’ve come to the intellectual and emotional conclusion that zoos are good institutions that serve critically important public purposes.

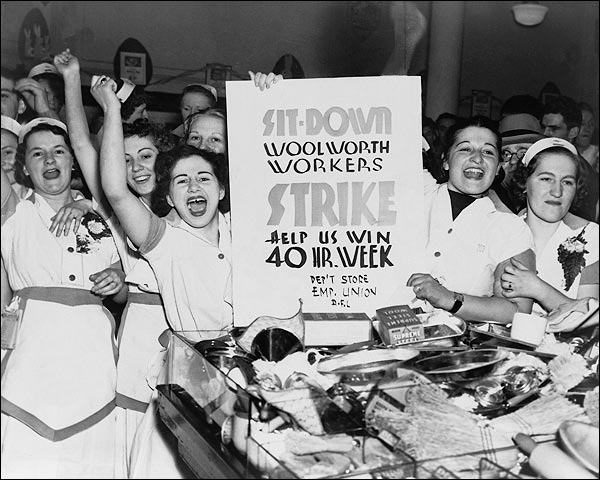

The American labor movement needs a jolt and Joe Burns’ new book, Reviving the Strike, delivers just the right shock treatment.

Debunking commonly held assumptions about labor’s inevitable decline and extinction, Burns, a veteran union lawyer, argues clearly and persuasively that worker power is still possible — but will require a dramatic shift in thinking and strategy.

Don’t expect standard academic or progressive bromides about “coalition-building,” “corporate campaigns,” “organizing-to-scale” or “social unionism.” In taking on some of the labor left’s sacred cows — living wage campaigns, worker centers, etc. — Burns praises and honors the commitment, brains and tenacity of activists. But these approaches, he suggests, lack the singular component necessary to transform power relations in the political economy. That, he contends, is the capacity to stop production.

Burns makes his case in a tightly-written narrative. After the union insurgencies of the 1930s, Congress and the courts imposed a system he calls “labor control,” one designed to disable unions’ principal and primary weapon: the strike.

Tom Morello went from playing guitar in the L.A. club band Lock Up to arena-stage stardom as a founder of Rage Against the Machine. The Harvard-educated Grammy winner’s many other music projects have included Audioslave and his current solo, accoustic incarnation called the Nightwatchman. He is the classic rebel in the rain, an all-seasons champion for the rights of the underdog, one who performs at protests from Madison to Wall Street.

On the eve of a new tour in support of his World Wide Rebel Songs LP, Morello spoke to the Frying Pan about his new comic book, protest and a certain president who, like Morello, has a Kenyan father and white mother.

What was the first thing that ever made you mad?

Well, growing up as the only black kid in my school was one thing, but as far as global events it was Bobby Sands’ hunger strike in Ireland.

» Read more about: The Nightwatchman Speaks: An Interview With Tom Morello »

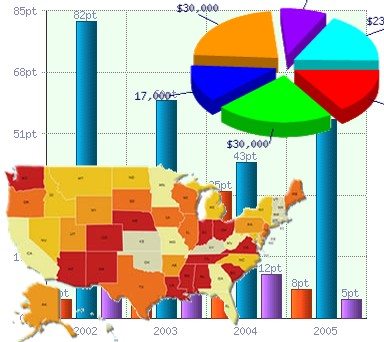

Things are seldom what they seem. Sometimes the distance between what we think we see and what is actually there is the result of personal prejudices. Sometimes it’s influenced by a kind of factual gerrymandering created by official sources and reinforced by the media. Most vacationers, for example would choose Carnival-happy Brazil in a moment over drug war-scarred Mexico. Unless they knew that Mexico has only 11 homicides per 100,000 people while halcyon Brazil is a murder leader with 31 homicides per 100,000 – a fact that seldom appears on Rio brochures or on our own six o’clock news.

And so it is here in America, where our own perceptions of unemployment and poverty often clash with the facts. The official calculation for the number of people out of work puts it at a single-digit — nine percent — while in California it nips at the heels of 13 percent.

» Read more about: Perceptions Lie: Why Official Facts Don’t Always Add Up »

[dc]J[/dc]ohn Densmore has been famous for longer than many of us have been alive. The drummer with the seminal 1960s L.A. band The Doors, Densmore parlayed his early success into a long career – not just as a musician but as a writer, actor, dancer, producer and social activist. He’s a native Angeleno (his childhood home is now an onramp where the 405 meets the 10) who cares deeply about his city and is clearly disturbed by the country’s right-ward turn

Densmore chatted recently with The Frying Pan about politics, Jim Morrison’s legacy and the subject of his upcoming book – greed.

Okay, let’s start with a rant.

I’ve been thinking about how the eight years of the Bush era brought us back towards feudalism – we’ve been feuding a lot. And of course the gap between the rich and poor is the worst in our history and the middle class is the glue between the upper class and the working class,

On the alternate Earth where some pundits live, the worst thing to ever befall Americans during the Great Depression was the New Deal. To them, federal recovery programs were wasteful extravagances that straight-jacketed men of wealth from creating jobs while inventing a nation of loafers. Some revisionist historians have even suggested that the Depression wasn’t as bad as people say it was – at least not Grapes of Wrath bad. These Depression deniers and the fairy tales they spread on talk radio and in blogs help explain why today’s political wilderness rings with the sound of falling axes as Congress merrily chops down the social programs that protect the poor, unemployed and injured.

Men and women grow old and die, but there are documents, both large and small, that loudly declare these new interpretations of the Depression to be the myths they are. One of the small but forceful records is White Collar,

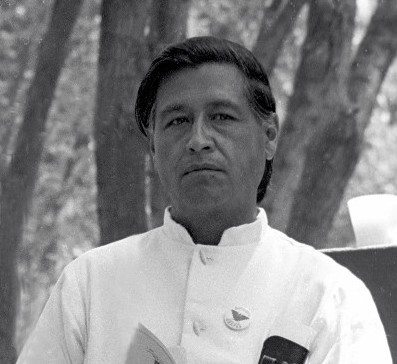

Last May, at a public meeting the National Park Service held in Oxnard to gather stories about the farmworkers movement, a man in his 50s came up to Martha Crusius. He told her about a rally he’d attended with his parents, migrant workers from Mexico, back in the 1960s.

“He was a little kid back then, and he really didn’t understand it,” Crusius says. “But he remembered that there was this small, soft-spoken Mexican guy leading the rally, and he was someone people really looked up to.” While listening to others testify at the meeting, he realized what he’d witnessed. “That man,” he told Crusius, “was Cesar Chavez.”

Crusius is director of the National Park Service’s Cesar Chavez Special Resource Study, an effort to curate and preserve the legacy of the iconic civil rights leader and United Farm Workers co-founder for future generations. It’s an effort that fits neatly,

“[T]he ruling elite […] have created societal institutions that have subdued young Americans and broken their spirit of resistance to domination.” So claimed psychologist Bruce E. Levine in his article “8 Reasons Young Americans Don’t Fight Back,” which appeared on AlterNet last July.

The author of Get Up, Stand Up: Uniting Populists, Energizing the Defeated, and Battling the Corporate Elite cited a 2010 Gallup poll that asked American workers, “Do you think the Social Security system will be able to pay you a benefit when you retire?” Seventy-six percent of 18 to 34-year-olds responded “No.” These young workers are currently paying Social Security taxes yet expect no return on their money.

For Levine, their evident acquiescence to this shafting is a strong indication that the “ruling elites” have succeeded in breaking the spirit of young Americans.

Burdened with student loans, overmedicated with anti-depressants and battered into consumerist passivity —

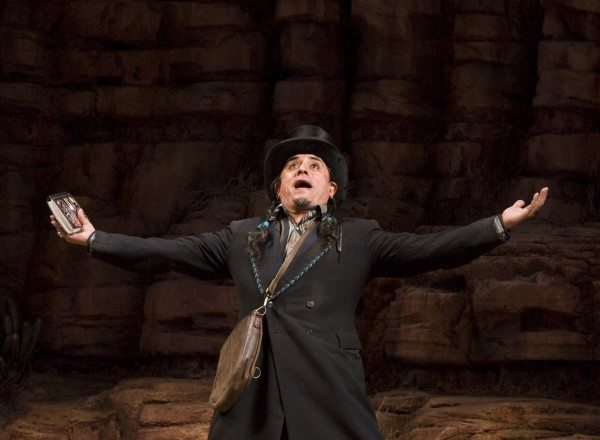

[printme]Richard Montoya got a surprise not too long ago. The playwright-performer of L.A.’s satirical comedy troupe, Culture Clash, discovered that a book of plays his company had performed over the years had been swept up in a contemporary American controversy. Namely, the shutting down of the Mexican-American Studies Program at Tucson Magnet High School. The book was part of the program’s curriculum until Arizona’s Attorney General, Tom Horne, found the program to be insufficiently patriotic under a new state law.

Horne will be appearing before the Ninth Circuit Federal Court of Appeals in a matter of months. Meanwhile, Montoya’s new play, American Night – a picaresque view of American history through the eyes of a Mexican immigrant – has received good reviews at the Oregon Shakespeare Festival in Ashland, where it is being performed through September. The Tucson brouhaha re-ignites a debate about the purpose of American political theater with a social justice message.