Culture & Media

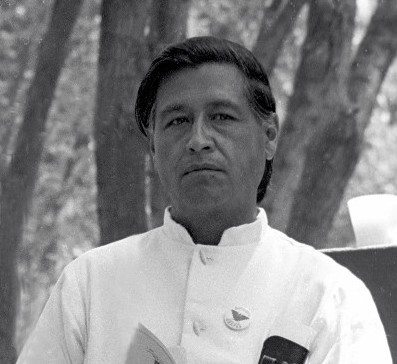

To Praise Cesar

Last May, at a public meeting the National Park Service held in Oxnard to gather stories about the farmworkers movement, a man in his 50s came up to Martha Crusius. He told her about a rally he’d attended with his parents, migrant workers from Mexico, back in the 1960s.

“He was a little kid back then, and he really didn’t understand it,” Crusius says. “But he remembered that there was this small, soft-spoken Mexican guy leading the rally, and he was someone people really looked up to.” While listening to others testify at the meeting, he realized what he’d witnessed. “That man,” he told Crusius, “was Cesar Chavez.”

Crusius is director of the National Park Service’s Cesar Chavez Special Resource Study, an effort to curate and preserve the legacy of the iconic civil rights leader and United Farm Workers co-founder for future generations. It’s an effort that fits neatly, if counterintuitively, in the agency’s mission, which not only includes historic preservation and a nationwide staff of “interpretative,” or storytelling rangers, but also has a mandate under current director Jon Jarvis to reach beyond middle-class wilderness lovers and history buffs.

“We’re definitely interested in telling the whole story of American history,” Crusius says. “It’s not all white and it’s not all dead.”

She heard a lot of Chavez stories from labor organizers, from the children of farmworkers, from farmworkers themselves.

“There were people who came to our meetings who pulled me aside and said ‘I worked on the boycott and they sent me to Chicago, and it was the first time I’d ever seen a big city,’” Crusius remembers. “There were other people who said, ‘My parents worked in the fields so I could go to college, and Chavez was the one who inspired me.’”

One man stood and said, “I used to play pool with Cesar Chavez,” though the man declined to comment on the labor leader’s skills as a sharp. “This history is still alive,” Crusius says.

Alive, yes, but not necessarily remembered with the acuity that should accrue to Chavez’s legacy – which is drawn from relatively recent events whose influence extended far beyond the fields of California. East Coast Baby Boomers who grew up in the 1960s and 1970s still regard grapes uneasily in the grocery store; two dozen streets in U.S. cities bear his name. Even Barack Obama’s campaign slogan owes to the movement Chavez founded with Dolores Huerta.

But few remember what fed the urgency behind the chants of ¡Si, Se Puede!, a slogan that came out of a 1971 conversation between Arizona labor leaders and Chavez during one of Chavez’s many long fasts, this one to protest an Arizona law prohibiting strikes and boycotts. Nor can many people who weren’t involved recall the details of the Great Delano Grape Strike that began with Filipino workers and launched one of the most successful boycotts in history – much less realize how central to U.S. politics that movement subsequently became.

The park service’s project, which was ordered by legislation Labor Secretary Hilda Solis authored in 2007 while serving in the U.S. House, is meant to resurrect those stories and give official recognition to a definitive American story that’s continuously in danger of slipping away.

Crusius says it’s too early to predict whether the park service will help administer interpretative exhibits at a series of historic sites or designate a single historic park or route. A Cesar Chavez National Monument has a nice ring to it; the question is where to put it. (Last week the Interior Department added to the National Register of Historic places Chavez’s retreat in the California town of Keene.)

In the eight cities where the agency held meetings — six in California, two in Arizona — “people felt very passionate about why their place matters,” Crusius says. We heard, ‘You can’t just tell this story in Delano at 40 Acres.’ Significant historic events took place in Salinas, in Fresno and in Phoenix.’”

People also reminded her that history isn’t preserved just in places, but in stories. A number of those have been archived on LeRoy Chatfield’s Farmworker Documentation Project, including audio interviews with Chavez and his brother. Richard Chavez, before he died July 28, granted a number of interviews about the Chavez’s family history, as well as about his days traveling the world on behalf of la causa. In one interview, he told of watching grapes rotting on the supermarket shelves in New York City – “you couldn’t give them away” — and in Oslo, Norway he saw ships pull into the harbor carrying grapes that dockworkers would refuse to unload.

It’s fascinating material, made all the more astonishing by how remote it seems now. It even felt that way for Richard Chavez. “Sometimes it’s kind of hard to believe that it happened,” he said. “But I know it did, because I was there.”

-

The SlickJanuary 27, 2026

The SlickJanuary 27, 2026The One Big Beautiful Prediction: The Energy Transition Is Still Alive

-

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 29, 2026

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 29, 2026Are California’s Billionaires Crying Wolf?

-

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026Amid the Violent Minnesota Raids, ICE Arrests Over 100 Refugees, Ships Many to Texas

-

Dirty MoneyJanuary 30, 2026

Dirty MoneyJanuary 30, 2026Amid Climate Crisis, Insurers’ Increased Use of AI Raises Concern For Policyholders

-

Featured VideoFebruary 4, 2026

Featured VideoFebruary 4, 2026Protesters Turn to Economic Disruption to Fight ICE

-

The SlickFebruary 2, 2026

The SlickFebruary 2, 2026Colorado May Ask Big Oil to Leave Millions of Dollars in the Ground

-

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 5, 2026

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 5, 2026Lawsuits Push Back on Trump’s Attack on Child Care

-

Column - California UncoveredFebruary 6, 2026

Column - California UncoveredFebruary 6, 2026What It’s Like On the Front Line as Health Care Cuts Start to Hit