Culture & Media

Lights, Camera, Civil Rights!

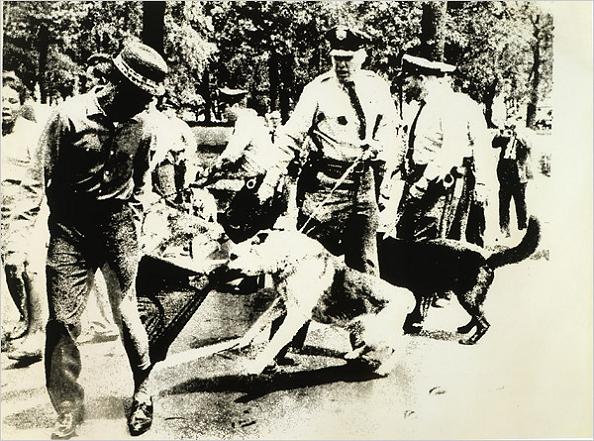

Andy Warhol, "Race Riot," 1963

(Editor’s Note: The Help, a Hollywood film set in the Deep South during the civil rights struggle, recently scored box office gold. It seemed a rare moment in which social activism was successfully married to commerce. But was historical accuracy sacrificed for popularity – especially to reach white audiences? Two veteran political activists discuss The Help and put it in context. Today Peter Dreier compares this movie with the lesser known The Long Walk Home. Tomorrow: Vivian Rothstein, who participated in the Mississippi Freedom Summer, offers another view of The Help.)

Film director Tate Taylor scored a late-summer box office smash with his adaptation of Kathryn Stockett’s novel, The Help. A surprise hit with movie critics, too, The Help is set during the racial battles of 1963. It focuses on the efforts of African American maids to maintain their dignity despite the routine discrimination and vicious slights they confront while living in segregated Jackson, Mississippi.

Their employers – middle-class white families whose husbands work and whose wives play bridge and organize Junior League charity events – pay the women less than minimum wage, expect them to clean their homes, shop for their food, cook their meals, and raise their children. The whites think nothing of using the N-word in front of the maids, generally treat them like dirt and show little concern that these women have children of their own who get less attention than the white kids they nurture from infancy to teenage-hood. The Junior League’s queen bee even organizes a campaign to require black maids to use separate bathrooms.

The Help flatters white audiences despite – or rather, perhaps because of – its historical inaccuracies. The film’s maids are depicted as helpless and we see little about their lives outside work — including their own families, their churches and neighborhoods — or of the civil rights movement that was mobilizing and dividing both blacks and whites that summer. The only acknowledgement of that movement is the maids’ response to the murder of NAACP leader Medgar Evers – yet even here they and other Jackson blacks are shown merely cowering in fear.

In true Hollywood fashion, it takes a white woman, Skeeter (Emma Stone), to empower the maids. Skeeter is a recent Ole Miss graduate who returns home to Jackson and embarks on a writing career by compiling a local oral history viewed from the perspective of the city’s maids. She begins her clandestine interviews with a friend’s maid named Aibileen (Viola Davis), who reluctantly agrees to talk despite her fears that it could cost her job. Aibileen then persuades her feisty friend Minny (Octavia Spencer) to participate, but no other maids will talk with Skeeter.

Events, however, unleash the women’s pent-up anger. In real life the rage triggered by Evers’ assassination spurred Jackson’s black community to organize protest marches, meetings, and vigils – all of which were met with police violence. In The Help, though, the maids confine their protests to giving testimony to Skeeter for her history. While Skeeter’s book may be guaranteed to upset Jackson’s white elite, it’s hard to view it as a strategy for bringing change.

Twenty-one years before The Help, another film about African American maids enduring similar indignities appeared. Richard Pearce’s The Long Walk Home, in contrast to The Help, shows African American maids as active participants in the civil rights struggle — and remains a much more uplifting and realistic movie about the plight and pluck of black domestic servants confronting racism. Perhaps because of its honesty, The Long Walk Home flopped and today you cannot even buy a new DVD copy of the film. Nevertheless, it is a celebration of the unsung heroes of the civil rights movement, the rank-and-file participants whose names don’t show up in history books.

The film is set in Montgomery, Alabama during the 1955 bus boycott that launched the modern civil rights movement. It stars Whoopi Goldberg as Odessa Cotter, a black maid employed by Miriam Thompson, an upper-middle-class women played by Sissy Spacek (who also has a smaller role in The Help). This film has some of the same elements of domestic drama as The Help, including the relationship between Odessa and Miriam, and the ugly slights inflicted upon Odessa by Miriam’s family.

But the boycott is at the center of the film. Its well-known heroes – Rosa Parks, Martin Luther King, JoAnn Robinson, E.D. Nixon and other organizers for the NAACP, the Women’s Political Council, and the Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA) – are all off-camera. Instead, The Long Walk Home is about the grassroots activism of Montgomery’s everyday black citizens who participate in the highlyorganized carpool system set up by the MIA to take boycotters to and from work, and whose morale is sustained by rallies, church services and the hope that their actions will bring down the city’s despised segregated bus system.

On days when they miss the carpool, the maids (and other Montgomery blacks) have to walk to work. Many times, Odessa has to wake up several hours early in the morning, and return home long after dark, to make the eight-mile walk to and from work, leaving her feet with blisters and her husband and children without breakfast and dinner. Unlike The Help, again, The Long Walk Home examines how a city’s whites – and its power structure — maintained segregation. It shows how, at its root, Jim Crow was built on a foundation of economic control, political power and the vigilante violence of the Ku Klux Klan and the White Citizens Council.

In the film, for example, the Montgomery cops kick Odessa out of a public park — where she has brought the Thompson children for a picnic — because they are off-limits to blacks. We see white teenagers beating up Odessa’s daughter when she rides the bus in defiance of the boycott . When the middle-class White Citizens Council discovers that Miriam is helping the boycott carpool, it lets her husband know that his business will suffer – the local political establishment will deny him permits for his housing developments – if he doesn’t control his wife’s involvement. The council also threatens the black and white drivers in the MIA carpool with tire irons and other weapons, knowing that the police will look the other way.

The Long Walk Home was criticized upon release for having a white narrator (Miriam’s daughter, looking back about 15 years later), and for focusing on the white family. Yet this film, more than any other Hollywood confection about the civil rights years, offers viewers insights into the complex work of grassroots mobilization and the the quiet day-to-day courage needed to build a movement for social justice.

-

The SlickJanuary 27, 2026

The SlickJanuary 27, 2026The One Big Beautiful Prediction: The Energy Transition Is Still Alive

-

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 29, 2026

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 29, 2026Are California’s Billionaires Crying Wolf?

-

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026Amid the Violent Minnesota Raids, ICE Arrests Over 100 Refugees, Ships Many to Texas

-

Dirty MoneyJanuary 30, 2026

Dirty MoneyJanuary 30, 2026Amid Climate Crisis, Insurers’ Increased Use of AI Raises Concern For Policyholders

-

Featured VideoFebruary 4, 2026

Featured VideoFebruary 4, 2026Protesters Turn to Economic Disruption to Fight ICE

-

The SlickFebruary 2, 2026

The SlickFebruary 2, 2026Colorado May Ask Big Oil to Leave Millions of Dollars in the Ground

-

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 5, 2026

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 5, 2026Lawsuits Push Back on Trump’s Attack on Child Care

-

Column - California UncoveredFebruary 6, 2026

Column - California UncoveredFebruary 6, 2026What It’s Like On the Front Line as Health Care Cuts Start to Hit