In the fall of 2011, millions of Americans were drawn to a movement directly challenging dramatically rising income inequality. The Occupy Movement dominated public discourse and put economic unfairness at the center of policy debates. Yet only two years after Occupy began on Wall Street, efforts to redress still worsening income inequality have stalled. The national grassroots campaign to get House Republicans to enact immigration reform has not been matched by similar efforts to raise the minimum wage or end corporate tax loopholes, with advocacy for such policies no stronger today than before Occupy’s emergence. We even face the prospect of President Obama selecting Lawrence Summers, a longtime backer of the One Percent, as the new head of the Federal Reserve. Are activists preoccupied with other issues, or have people decided that challenging the power of the One Percent is not a winnable political fight?

This past weekend I came across two documentaries about dramatic wealth inequality in the United States: Alex Gibney’s November 2012,

Shadows reach,

dapple the asphalt.

Hawks whoop,

surfing air.

Tumble weeds cling

ready to roll.

Desert breath blows,

tree tops twist.

Sweat salts my skin.

I itch.

All it takes is one

red spark.

I kneel down—watch

as the wind

picks it up. I withdraw,

stare

at what I’ve unleashed

on every channel

No one knows.

Nothing can stop it.

I burn.

I don’t need anyone,

closer now—so high

I can’t stop.

———————————————————–

Marilyn N. Robertson’s work has been published in Speechlessthemagazine, The Boston Literary Magazine, Chopin with Cherries, A Tribute in Verse, and is forthcoming in The Poetry Mystique, to be published by Duende Books. She was a featured reader in “Viva Poetry,”

Why are so many Americans wary of labor unions? Unions are, after all, good for everyone who works for a living. In occupations with a high rate of unionization all the workers get paid more, even employees who aren’t in a union. As rates of unionization have fallen, so has compensation. One might expect unions to be all the rage with anyone who ever put in a hard day’s work. But this is not always the case, particularly in the United States.

Americans have WEIRD attitudes towards unions – as in, Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic. The Canadian behavioralists who coined this acronym were interested in how sweeping generalizations about human psychology and economic behavior might be incorrect if they were based on only one kind of (WEIRD) people, and reviewed a number of cross-cultural studies to make their point. To scholars at the University of British Columbia,

We couldn’t resist. The Fourth of July is the biggest and baddest of all barbecue bonanzas, and so we decided the Union Cookout needed a sequel for Labor Day. Labor 411 is here with our follow-up to last year’s grill special that includes some of the best union-made picnic and party goods around.

(Reposted from Labor 411.)

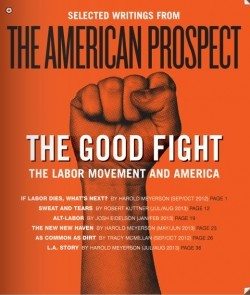

Check out this handy collection of American Prospect stories on the state of labor and the labor movement in the U.S. The anthology, The Good Fight, can be browsed online or downloaded for offline reading.

It features pieces by Robert Kuttner, Tracy McMillan, Josh Eidelson and Harold Meyerson — including Meyerson’s recent profile of the Los Angeles Alliance for a New Economy, “L.A. Story.”

Perfect reading for this Labor Day weekend!

A few days ago I had breakfast with a man who had been one of my mentors in college, who participated in the struggle for civil rights in the 1960s and has devoted much of the rest of his life in pursuit of equal opportunity for minorities, the poor, women, gays, immigrants — and also for average hard-working people who have been beaten down by the economy. Now in his mid-80s, he’s still active.

I asked him if he thought America would ever achieve true equality of opportunity.

“Not without a fight,” he said. “Those who have wealth and power and privilege don’t want equal opportunity. It’s too threatening to them. They’ll pretend equal opportunity already exists, and that anyone who doesn’t make it in America must be lazy or stupid or otherwise undeserving.”

“You’ve been fighting for social justice for over half a century. Are you discouraged?”

“Not at all!” he said.

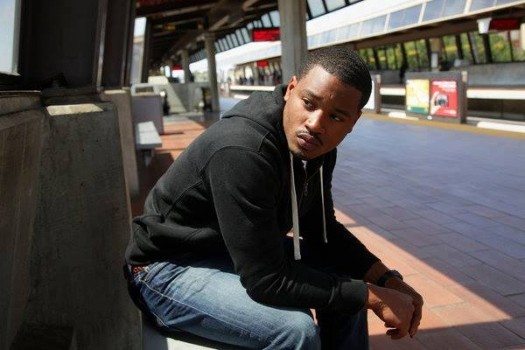

Fruitvale Station will not make many people’s lists as the feelgood film of the summer – it’s a semi-fictional account of the last day in the life of Oscar Grant, the troubled young black man who was mortally wounded by a transit police officer on an Oakland BART platform in 2009. Director Ryan Coogler’s debut movie opens with actual grainy cell phone footage, taken by bystanders, of the chaotic moments leading to Grant’s shooting after a melee had erupted on a train full of New Year’s Eve revelers.

Yet the story remains a powerfully optimistic work that shows Grant (Michael B. Jordan), in his last day alive, coming to terms with his criminal past as a small-time drug dealer. We watch as he tries to move his life in a new direction and become a better husband and father. And, despite Grant’s recurring moments of explosive personal confrontations, Coogler’s film knows when to pull back and take a restrained,

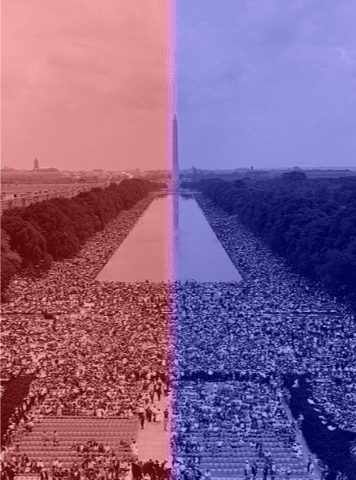

Fifty years ago, just a year out of high school, I sat in my parents’ small living room engrossed by images on the flickering black and white TV screen. Something called the March on Washington was running live — the whole event, as I recall, which network television did in those days. I’m not sure why I was not at work or why I was alone in the house, but I remember that tears came to my eyes, just as they do now as I think back on that day.

My parents were originally from the South, but both grew up in Southern California. My mother had been born in Mississippi, moved to Texas and then Inglewood. My father came from Texas to La Crescenta. After they married and my father became a minister, Northern California was home, but the ethos of white superiority and other ethnic and class inferiorities were engrained.

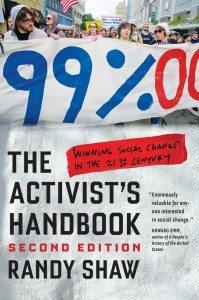

Last Saturday’s commemoration of the 1963 March on Washington spotlighted the power of grassroots activism. But it was no exercise in nostalgia. Activists are pushing for social change across the nation, and I discuss dozens of these campaigns in my new book, The Activist’s Handbook, Second Edition: Winning Social Change in the 21st Century, officially released today by UC Press. The book thoroughly revises and updates the 1996 edition, which the late Howard Zinn praised as “enormously valuable for anyone interested in social change.” The new edition adds my analysis of the strategies used by social movements around immigration reform, gay and lesbian rights, the Keystone XL Pipeline, school “reform” and other campaigns that really took off in the past decade.

While some believe the past 15 years have weakened the power of grassroots activism against big moneyed interests, I disagree. In fact, in writing the new book I realized that activism has increased since the original edition,

What would the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. march for if he were alive today?

America has made progress on many fronts in the half-century since King electrified a crowd of 200,000 people, and millions of Americans watching on television, with his “I Have a Dream” address at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. But there is still much to do to achieve his vision of equality.

Fortunately, many Americans are involved in grass-roots movements that follow in his footsteps. King began his activism as a crusader against racial segregation, but he soon recognized that his battle was part of a much broader fight for a more humane society. Today, at age 84, King would no doubt still be on the front lines, lending his voice and his energy to major battles for justice.

Voting rights: Along with other civil rights leaders, King fought hard to dismantle Jim Crow laws that kept blacks from voting.

» Read more about: Martin Luther King Jr.’s Spirit Is Still Marching »

See original feature by Gary Cohn, “Interpreter Bill Would Help Save Lives Lost in Translation.”

» Read more about: Lalo Alcaraz on California’s Need for Medical Interpreters »

Congressman John Lewis is the only survivor among the ten speakers at the March on Washington, a turning point in the civil rights movement that occurred 50 years ago, on August 28, 1963. The march is most famous as the setting of Martin Luther King’s famous “I Have a Dream” oration, but Lewis’ speech that day, representing the movement’s radical youth wing, provided a different kind of call to arms. It is a message that Lewis has continued to voice as a movement activist and an elected official.

Only a handful of the 250,000 people at event – officially called the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom to reflect the link between economic justice and civil rights – knew anything about the drama taking place behind the Lincoln Memorial. Under the leadership of A. Philip Randolph, the longtime civil rights and trade union leader, the march had brought together the major civil rights organizations as well as labor unions and religious denominations and women’s groups.

No one ever said housemaid or domestic. Pride matters more

And here’s the truth of it: she was Tantie, a grand-mothering

substitute chained to Miss B., a former Hollywood come-hither

and Tantie’s final mystery. I couldn’t name a single movie

Miss B had starred in but Mother told us she was a 1st-class bitch.

Thirty years later, watching late night television, I recalled:

I met that bitch once. Ill-preserved on celluloid, she fluttered

there amidst her ersatz brood but not in the same way I’d seen

her flutter decrees upon my Tantie. And my Tantie, once a muck-

a-muck in her own right (having flown an airplane solo in days when

most women and Negroes were grounded) half-fluttered in return—

to make sure her family had dimes and nickels. Tantie didn’t tell us

she was Miss B’s maid and I never knew a thing about it until I saw

this black-and-white movie with Miss B—half a star among stars—

given third place billing—nearly unrecognizable as the cold shrew

I remembered flaunting dipped pearls,

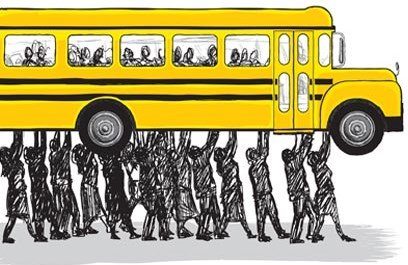

I wanted to cry after watching Go Public: A Day in the Life of an American School District. After the hour-plus video collage of complex and inspiring day-to-day interactions that make up our nation’s public schools, the film culminates in pleas from teachers, parents and maintenance staff to the Pasadena Board of Education to forestall millions of dollars in new budget cuts to the district’s schools.

I’ve been there myself, 25 years ago when my kids were in grammar school, pleading with Santa Monica School Board members to save school librarians and nurses, most of whose positions were eventually eliminated.

It’s so hard to understand how a city like Pasadena, where median home prices are in the $600,000 range, has had to face $6.5 million in education cuts in the past few years. These cuts have resulted in school counselors having to handle 480 students apiece,

Why is the nation more bitterly divided today than it’s been in 80 years? Why is there more anger, vituperation and political polarization now than even during Joe McCarthy’s anti-communist witch hunts of the 1950s, the tempestuous struggle for civil rights in the 1960s, the divisive Vietnam war or the Watergate scandal?

If anything, you’d think this would be an era of relative calm. The Soviet Union has disappeared and the Cold War is over. The civil rights struggle continues, but at least we now have a black middle class and even a black President. While the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan have been controversial, the all-volunteer army means young Americans aren’t being dragged off to war against their will. And although politicians continue to generate scandals, the transgressions don’t threaten the integrity of our government as did Watergate.

And yet, by almost every measure, Americans are angrier today.

Readers who have fought for social justice while waging a home-front war with parents who hold views diametrically opposed to theirs will take heart in Madeline Janis’ op-ed in Sunday’s Los Angeles Times.

The opinion piece, “Dad, Rush Limbaugh and Me,” is a wry meditation on family and political beliefs that was prompted by the recent death of the author’s father. However, the story specifically springs from an incident that occurred when Janis, who is the Los Angeles Alliance for a New Economy’s national policy director, helped move her father to an assisted living facility several months ago. She writes:

On the day we were packing, with both of us understandably on edge, I came across a stash of Rush Limbaugh caps, maybe half a dozen of them, each with a different year printed on the front. I couldn’t let it pass.

OMG! Was Gene Autry, the “singing cowboy” on TV and in the movies, really a radical?

I just discovered this Autry recording of the pro-labor song “The Death of Mother Jones,” about the great radical union organizer — Mary Harris Jones, sometimes called the “most dangerous woman in America” by her enemies — who died at 100 in 1930. Autry recorded the song in February 1931 during the Great Depression. It is so obviously pro-union that there’s no way Autry couldn’t have known what it meant.

Like many baby-boomers, I grew up watching Autry in his cowboy films and his popular television show. He was famous for singing cowboy songs like “Back in the Saddle” and “Tumbling Tumbleweeds,” as well as popular hits like “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer,” “Here Comes Peter Cottontail,” and “Frosty the Snowman.”

In the 1930s, 1940s and 1950s, he was one of Hollywood’s biggest stars.

The baby was lifted in its flowing shroud

And carried through the red-lit streets,

Floating above the raised fists of men

In headcloths. The wrapped body a cloud,

Pall burden so light, it seemed weightless

Crowning the mad cortege. That shape

Once living in her arms—that shape

I mirrored, newborn at my breast. Shroud

So light it became an unsupportable weight,

As TIME fell open before me. I was the street

Going up in flames, but couldn’t see it, in the cloud

Of fire, her face. What dark veil or wall of men

Hid her? TIME opened to the images of men.

I couldn’t see her; just her grief, unraveling shape,

White streaming from the breast. That cloud

Of chants, bitter witness to the small shroud

Held high. She stood away from the fiery street—

The monument of her shadow,

Dear Brother,

In my job I use

a tiny torch

it opens and closes as I stitch

metal with a syringe of light

bright as a drop of sun. I try

not to look but two white spots

burn at the back of my eyes.

In one I see

the other jobs I’ve had –

cleaning up inn rooms

— someone else’s stain.

In the other: years

nearly starving on the farm

never enough, no wheels, no

way to town.

Between

these two spots the men

who wanted something and me

just trying to make it work.

Possession

implies something remains,

but want is all it is.

Dear Brother,

in little squeezes of light

that whisper and cut

are months and years my history

turned white

in this brazier that captures and holds,

this chamber

where everything

hardens and glows.

——————————————————–——————————————————–

Source: The Dos Passos Review,

(Dave Zirin writes about sports and society for the Nation, where this post first appeared. Republished with permission.)

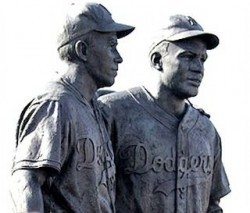

Sometimes it’s all just too damn much. First came word this week that the famed Coney Island statue of Jackie Robinson, standing alongside Pee Wee Reese as sporting symbols of racial progress, had been defaced, with “die n***ers,” “f*ck Jackie Robinson and all n***ers,” and “Heil Hitler” scrawled across it. It’s quite the capstone to a summer that started with the sweetly hopeful biopic, 42, about Robinson’s early career and post-racial promise. There is no doubt if Robinson still walked among us, he wouldn’t be shocked at the vandalism of his statue. He’d grit his teeth and set to cleaning it with his bare hands as a vein throbbed dangerously on his temple. This is the world—and the country—Jackie Robinson knew all too well.

» Read more about: Jackie Robinson, Trayvon Martin and the Ebony Boycott »