What do nurses, Waffle House servers and Uber drivers have in common? Violence on the job — and a movement to end it.

From Chicago to San Jose, California, rideshare drivers are working together for higher pay, safer work and better jobs.

“Due process” for deactivations would include clear rules, guidelines and appeals before loss of income.

For the first time, they could qualify as employees and enjoy benefits and rights that have been off-limits for years.

A guide to three key Golden State ballot proposals.

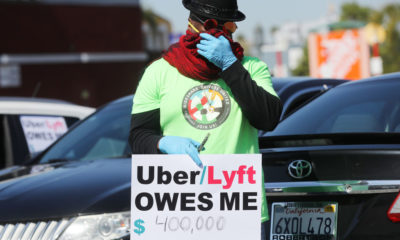

Rideshare companies spent $203M to pass a California measure limiting driver rights. A lawsuit says its fine print could block unions.

The most expensive ballot proposition in California history has won, although its opponents complained of being harassed online.

Gig companies are threatening to eliminate thousands of jobs if their ballot measure doesn’t pass.

Major endorsements arrive as critics worry the measure will be disastrous for California labor.

Lyft and Uber drivers’ early pandemic experiences have soured them on the companies’ ability to keep their workers safe.

An Economic Policy Institute study concluded that rideshare drivers nationwide take home an average of $9.21 an hour after expenses.

Co-published by the American Prospect

If AB 5 becomes law it could open the floodgates to similar legislation in other states. Uber and other companies may then find themselves on the defensive.

Although rideshare apps and other “gig economy” jobs are often billed as ways for workers to make extra cash in their spare time, that hasn’t been the case for many.

Co-published by the American Prospect

The strike by Uber and Lyft drivers came amidst highly anticipated initial public offerings from the two rideshare giants.

This week Capital & Main launches an ongoing project focusing on the broken economics of what is, according to one recent MIT analysis, America’s most expensive state.

Co-published by Fast Company

Consumer campaigns have existed for more than a century, but the Trump presidency has galvanized activists and accelerated their work.

Twenty-six-year-old Takele Gobena is part of the “on-demand” economy, working full-time as a driver for Uber and part time for Lyft. The Ethiopian immigrant quit his job at the Seattle-Tacoma International Airport and purchased a new car to drive for the ride-hailing firms, believing it would make him a better provider for his one-year-old daughter. Instead, Gobena now finds himself in debt and, after expenses, making well below minimum wage. But because Uber and Lyft drivers are classified as independent contractors, Gobena is not protected by minimum wage laws.

Gobena’s plight is an increasingly familiar one. A new report from the National Employment Law Project, “Rights on Demand: Ensuring Workplace Standards and Worker Security In the On-Demand Economy,” highlights the problems so many on-demand workers face: “Characterizing workers as non-employees has serious negative consequences for them: non-employees have no statutory right to minimum wage, overtime pay,

It was 2008 and presidential hopeful Barack Obama was inspiring millions of people with his promise to disrupt politics as usual – and a new startup called Airbnb was turning that enthusiasm for change into millions of dollars. Denver, the site of that year’s Democratic National Convention, was expecting 80,000 people to come watch the senator from Illinois accept his party’s nomination. The city had space for less than half.

“Obama supporters can host other Obama supporters,” is what CEO Brian Chesky recalls thinking to himself. In a profile of the company, the Huffington Post notes how that idea was turned into cash. “Airbnb, which lets users rent out part or all of their homes, blasted bloggers in Denver with company information.” It “sold ‘Obama O’s’ cereal around town,” garnering news coverage as “an innovative solution to the city’s lodging crisis.”

Founded in 2007, Airbnb is today valued at more than $25 billion and the for-profit sharing economy it helped usher in is no longer so new.

» Read more about: The Sharing Economy's Liberal Lobbyists »