A new documentary about Cesar Chavez’s mentor offers lessons for activists in dark times.

The Robert F. Kennedy farmworkers plan is limited, but it is the best option for many.

An innovative organizer for three unions, Ross also challenged U.S. policy toward Central America.

When writer and veteran union organizer David Bacon speaks of “people who travel with the crops,” he means the agricultural workers who move from place to place to cultivate and harvest California’s fields. They are also the subject of his newest work of photojournalism.

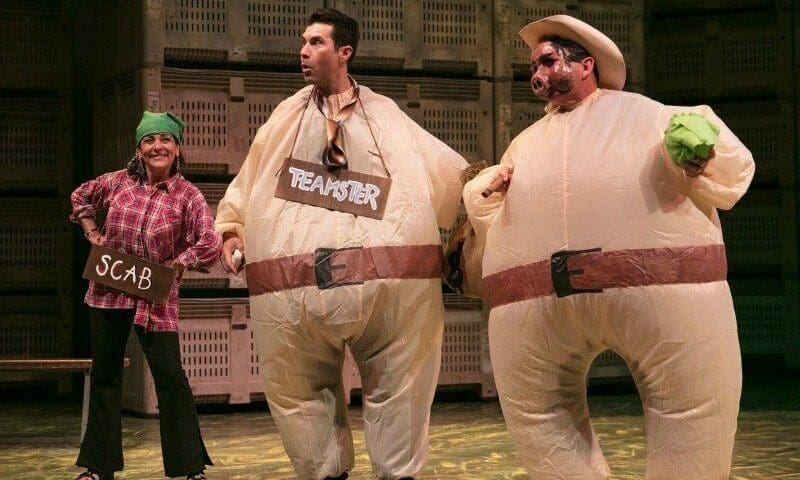

The time for Diane Rodriguez’s play is 1970, and the immediate setting is the office of El Malcriado, the newspaper founded by Dolores Huerta and Cesar Chavez in Delano, California.

When Cesar Chavez led a band of farm workers on their historic 300-mile march from Delano to Sacramento half a century ago, they prominently displayed banners of the Virgin de Guadalupe throughout the line. Why? Because that image held symbolic weight far beyond any other the group could carry.

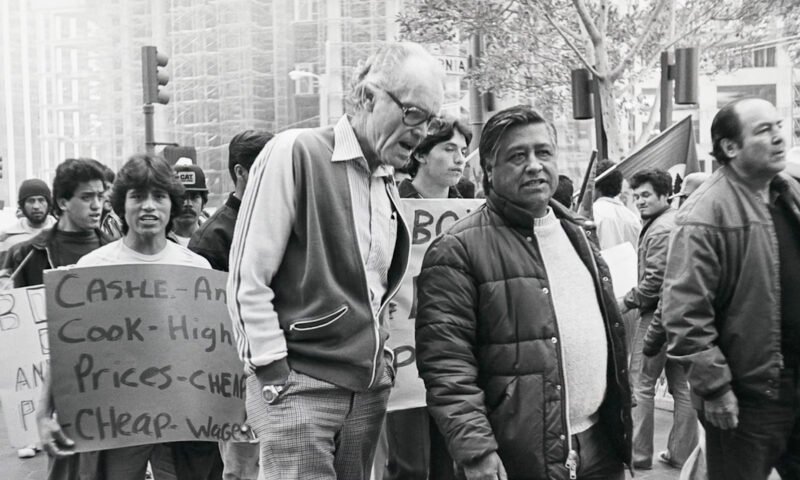

Sometimes the most interesting, and influential, figures in history are anything but household names. A case in point is Fred Ross, one of the greatest organizers of the 20th century.

The police stop a young man. An officer shoots, killing him. The officer claims self-defense, that the killing was warranted.

The community, having endured years of unequal treatment at the hands of law enforcement and other municipal agencies, responds in anger. Protests ensue. Hard feelings persist, as do demands for law-enforcement accountability.

Sound familiar? No, this is not the case of 18-year-old Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri. The young man in question was Augustin Salcido, 17, and the incident occurred in Los Angeles more than six decades earlier. The Internet did not exist at that time and local television audiences were miniscule, so the Civil Rights Congress of Los Angeles produced a pamphlet, Justice for Salcido. In its introduction, author and civil rights advocate Carey McWilliams described the killing as part of a historical pattern of “continued suppression of the Mexican minority.”

Fred Ross,

» Read more about: Fred Ross, Cesar Chavez and Lessons for Ferguson »

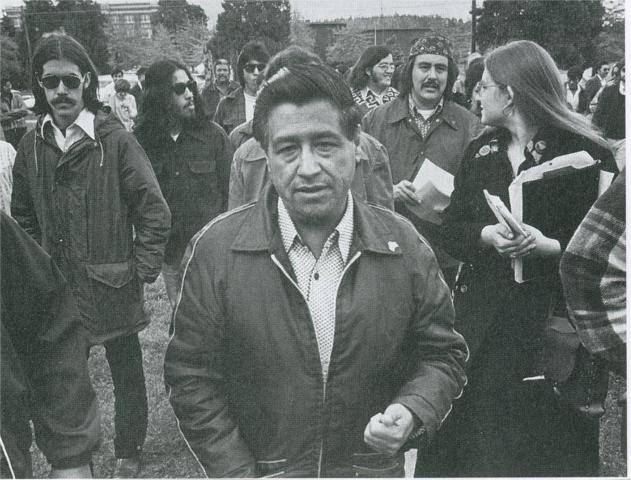

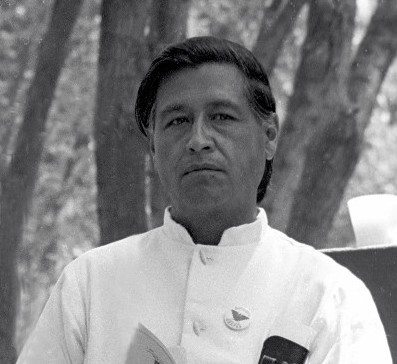

Many people thought Cesar Chavez was crazy to think he could build a union among migrant farmworkers. Since the early 1900s, unions had been trying and failing to organize California’s unskilled agricultural workers. Whether the workers were Anglos, Chinese, Japanese, Filipinos or Mexican Americans, these efforts met the same fate. The organizing drives met fierce opposition and always flopped, vulnerable to growers’ violent tactics and to competition from a seemingly endless supply of other migrant workers desperate for work. So when Chavez left his job as a community organizer in San Jose in 1962 and moved to rural Delano to try, once again, to bring a union to California’s lettuce and grape fields, even his closest friends figured he was delusional.

Within a decade, however, the United Farm Workers (UFW) union had collective bargaining agreements with most of California’s major growers. Pay, working conditions and housing for migrant workers improved significantly.

There haven’t been, to put it mildly, many films about America’s labor movement. Take away Salt of the Earth (1954) and Norma Rae (1979) and what are you left with? Cesar Chavez, then, offers to fill a cavernous void in the public’s knowledge about both union organizing and the history of the country’s mostly Latino agricultural workforce. Directed by the Mexican actor and film producer Diego Luna (Y Tu Mamá También, Elysium), the film follows Chavez (Michael Peña) from the time he parted company with the grassroots Community Service Organization (CSO) to the signing of union contracts with growers following a successful consumer boycott of table grapes.

Working with a screenplay by Keir Pearson, Luna wisely passes on a sweeping Gandhi-style treatment of Chavez’s entire life. This allows Luna and cinematographer Enrique Chediak to linger on the arid poetry of life in California’s Central Valley (played here by Sonora,

When Diego Luna was growing up in Mexico he’d sometimes hear references to Cesar Chavez and the union of farm workers he had organized in America. Luna, who would become one of his country’s leading film stars, remembers being struck as a 13-year-old by television images of Chavez’s funeral – the man was so modest, his coffin was an unpainted wooden box. A few years ago Luna began assembling a production company to film one critical chapter in Chavez’s life – the 10-year period in which he formed the United Farm Workers Organizing Committee and which culminated with the triumph of the consumer grape boycott. Cesar Chavez opens this week and Luna, while in Los Angeles to promote the film, spoke to Capital & Main about the movie, the man and the movement he created.

Capital & Main: Your film is a biography but is there something more behind it?

I think its message is of what we can do when we unite.

» Read more about: Interview With ‘Cesar Chavez’ Director Diego Luna »

Spring equinox always arrives in what feels like the middle of winter. Snow falls in the Northwest while the Northeast tries to dig out from under the most recent storm and ice still covers Midwestern roads. Even in Los Angeles, spring does not really feel like, well, spring until sometime in late April or early May. The foundational spring stories of the Northern Hemisphere also have that hidden element.

Passover in the Jewish tradition tells the story of a people oppressed by enslavement in Egypt, the dominant empire of its time. Over and over again terrible experiences overtake the land, but the slave masters refuse to let go. A plague of frogs is not enough. Nor locusts. Nor dying animals. Nine times the plagues come and the masters will not relent. Then, suddenly, with number ten, the slaves are released, or actually, told to leave. It could have happened after the first disaster.

» Read more about: Spring’s Awakening and the Dawn of Change »

Activists, organizers and elected officials across the United States have come together to urge President Barack Obama to award posthumously the Presidential Medal of Freedom to the legendary organizer, Fred Ross Sr. The first to organize people through house meetings, a mentor to both Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta, and a pioneer in Latino voter outreach since 1949 when he helped elect Ed Roybal as Los Angeles’s first Latino council member, Ross’ influence on social change movements remains strong two decades after his death in 1992. If there were a Mount Rushmore for community organizers, Ross’s angular face would be on it. Here is a brief summary of Ross’s remarkable legacy, along with instructions on how to get your message of support to President Obama in time for the February 28 deadline.

Like all activists familiar with his work, I had a reverence for Fred Ross, Sr. before I knew the full record of his accomplishments.

President Obama this week designated the home and burial site of the legendary United Farm Workers (UFW) leader, César Chávez, a national monument. Known as La Paz, short for Nuestra Señora Reina de la Paz, or Our Lady Queen of Peace, the site is in Keene, California

AFL-CIO President Richard Trumka says the designation is a

fitting tribute for a man whose campaign for civil rights and respect for workers struggling in the shadows broke new ground and left an indelible mark on the pages of American history. The farm worker movement that Chávez is most often associated with was never deterred by their lack of money or clout. These workers knew that together they could form a mighty force for justice. Their collective action through the United Farm Workers brought national support to the moral cause and won historic victories and protections for agricultural workers.

» Read more about: César Chávez Home Becomes a National Monument »

Fifty years ago I graduated from high school on the other side of town from where Dolores Huerta had a decade earlier. My high school class will hold its reunion this fall. Also 50 years ago, Huerta and Cesar Chavez founded the United Farm Workers a few miles further south in Delano. The UFW just celebrated its half-century at its annual convention, this year in Bakersfield.

Long before I met Chavez I had heard of the legend. He had learned about organizing under Fred Ross, who was criss-crossing the state building the Community Service Organization (CSO) network among the Spanish-speaking urban barrios. But when Chavez wanted to expand CSO’s mission to organize farm workers in the Central Valley, CSO said no. So he did it on his own, with no money, no budget and only a handful of contacts. He went to Delano and began to work among the vineyards,

» Read more about: Fields of Dreamers: Looking Back at the UFW »