Organizing Principles

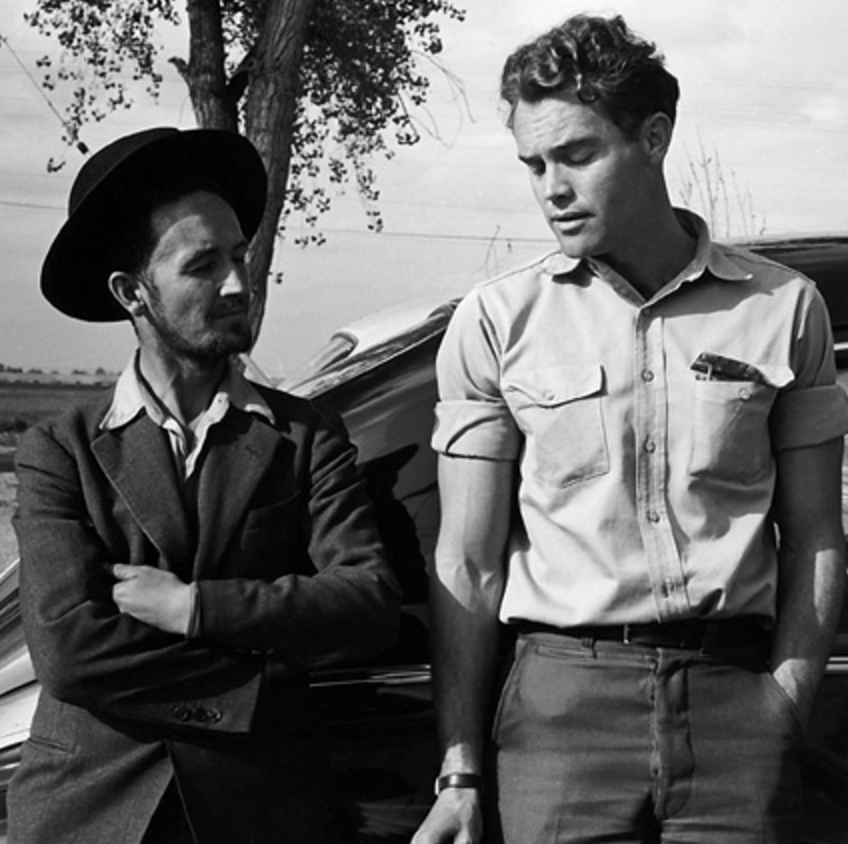

Man on Fire: Gabriel Thompson on the Life and Times of Legendary Organizer Fred Ross

Sometimes the most interesting, and influential, figures in history are anything but household names. A case in point is Fred Ross, one of the greatest organizers of the 20th century.

Sometimes the most interesting, and influential, figures in history are anything but household names. A case in point is Fred Ross, one of the greatest organizers of the 20th century.

Without Ross, the world may never have seen the rise of Cesar Chavez and the farm worker movement that galvanized a generation of activists. It was Ross who first recruited and mentored Chavez, as well as the co-founder of the United Farm Workers, Dolores Huerta.

But Chavez and Huerta were just two of the thousands of people whose lives were touched by Ross during an extraordinary 50-year span that began with his work in the Kern County migrant camp immortalized by John Steinbeck in The Grapes of Wrath. His achievements also included the creation of the Community Service Organization, which played a seminal part in the political mobilization of Mexican Americans across California.

Ross, who died in 1992, was inducted into the California Hall of Fame by Governor Jerry Brown and is now the subject of a long-overdue biography, America’s Social Arsonist. Capital & Main recently sat down with author Gabriel Thompson for a conversation about a man whose legacy can be found in the legions of Ross-trained organizers who continue the work he called “the forever project.”

The issues that he’s working around are a sweeping history of the struggles that were occurring in the West, in California and in the country. So I was interested in finding Ross as a character who’s moving through all that, but also because he was an organizer. I spent a few years as an organizer, enough to know that it’s not easy. Also, it’s easy to miss the work that organizers do, because it’s often behind the scenes. Ross is constantly pushing others forward as he’s organizing over a whole host of issues. His story is worth telling because it reminds us that history is made in quiet places by people who aren’t behind a mike or leading marches.

Why has his history largely been forgotten?

Ross struggled to write, never really had a book of his published until way later. He was not the kind of person who gave very many interviews. One of his sayings about organizing is that an organizer is one who does not lead but gets behind the people and pushes. He spent his life doing that, so he was an easy person to overlook.

He loved the kind of work that would have bored [Saul] Alinsky to tears. He loved the door knocking, teaching people how to make phone calls, the sort of nitty gritty stuff. We think of organizing and social change, and sometimes we flash to these dramatic marches or these inspiring confrontations. That’s a very small amount of what goes into organizing. How do you move someone into action? How do you get eight people into this room? How do you turn that eight into 80? That’s what he really spent his life doing.

Was his optimism shaken at all by the events that he witnessed, such as the demise of the United Farm Workers as an organizing union? Or the rise in California of a powerful anti-immigrant, anti-Latino political movement?

I really don’t know what could have shaken his optimism. Ross was someone who, if you think about one of the darkest moments of U.S. history, was working at an internment camp in Idaho, trying to provide community services to ethnic Japanese, mostly Japanese-American, U.S. citizens who had been swept out of the West Coast. It was the harshest climate you can imagine.

That’s a pretty big slap in the face of optimism, but I never got the sense that he really got depressed. He mentions one of his early conversations with Chavez, where Chavez is just getting started under Ross. He’s kind of watching Ross and he’s excited about the fact that things are moving and that they’re organizing successfully. He asked something along the lines of how long will this take? Ross says, this takes forever, there is no end to this project.

The other piece to remember about Ross is that he’s not out traveling on the road for months at a time, sleeping in people’s living rooms, because he’s sacrificing. He loves the work. He wanted to make an impact. He thought it was the most important thing he could possibly be doing. That really makes up for a lot of other depressing aspects of life.

You make clear in the book that his family paid a pretty steep price. As someone who has spent some time as an organizer, what did you take away from what you saw about Fred Ross’ single-minded dedication to his work?

Well, there’s no doubt that family came second. What was interesting to hear from Ross himself in [his] tapes and when he’s writing is he’s completely not trying to hide that fact. He sees it as a key requirement to be an organizer. It was a different era. When I look at the organizing landscape today, I think it’s changed. People have personal lives, they want to enjoy other things. You still have people who are organizing fanatics, but that’s not what’s expected from everyone. I think he was upfront that he didn’t pay a price – his family paid a price.

What can young organizers who want to change the world learn from Fred Ross, both in terms of his achievements and the style in which he operated – and the cost that he sometimes brought to those around him?

There’s tons of incredibly talented organizers who also have well-rounded lives. His son, Fred Ross Jr., is an example of someone who is incredibly dedicated to labor organizing, community organizing and who also is very involved in his family. What Ross reminds us now is, first of all, the importance of being curious and of listening. When I heard about how he had swept both Cesar and Dolores into a life of organizing, I imagined this guy who is incredibly charismatic. What he really was, he really focused on people, he listened and he was curious. The other thing is that he made people work. It wasn’t like, “I’m this organizer and I’m going to come in and I’m going to make everything really easy for all of you and find solutions for you.” It was like, “No, if this is what you guys have decided you want to do, I’m there with you.”

Part of an organizer’s role is to give people the ability to take on more themselves – just making sure that you’re not in it alone.

What do you think Ross would make of the rise of populism on the left and the right? Would he see it as an opportunity for organizing?

I don’t think there is any time when Ross didn’t see anything as an opportunity for organizing. I think he would have been excited. Ross was very passionate about the power of voting. He wasn’t a believer really in politicians. The vote was an extension of people’s formal ability to hold others accountable. He really made history in East L.A. in his campaigns to register Latinos to vote.

I think he would have been pretty excited by the idea that lots of people are giving small amounts of money. He was never able to break through on the funding question. His organizations, including the CSO, struggled with money. The goal was to have it self-funded by working-class Mexican Americans themselves. They never quite got there. UFW did a better job with that.

Where do you see Ross’s legacy today?

You can see it most in the people that are doing work now, who have been trained or touched or mentored or influenced in some way by Ross or by the people that he trained. In the ‘70s and ‘80s, he trains maybe 3,000 people that are going through the United Farm Workers, at a time when there’s not a lot of in-depth organizing training going on in this country. The legacy, obviously, of the CSO sort of being the incubator for the United Farm Workers and its ideas about what unions can be, has spread out.

It’s important to remember that the UFW didn’t pop up out of nowhere in 1965 when people go on strike. There’s people working for decades beforehand. There’s something very inspiring to me about someone who came from this middle-class, sheltered family and sort of stumbled his way into organizing and then spent his whole life in the trenches.

By the end, he’s living in a primitive one-room cabin on Social Security checks, mattress on the floor. So I think he was someone who deserves his due.

Chavez, towards the end of his life, moved away from organizing. It’s not clear in your book whether Ross had serious misgivings about Chavez in the latter stage of his own life.

Ross never told anyone — he was incredibly loyal to Chavez. Chavez made a series of decisions, and you look back now and you’re like, Man, if that had not happened, that would be great. I don’t know how else to feel. There’s a sense of tragedy about it. One of the painful aspects of it is that Ross had really drilled into Chavez — and he didn’t have to drill too hard because Chavez felt this as well — that organizations must encourage leaders at the base that want to push, that want to fight. Those people that Ross believed you had to go find at the grassroots are the same people in the end that Chavez sees as a threat to his power at United Farm Workers. Chavez gets involved in a lot of other things besides organizing: creating a sort of ideal community, a kind of commune, volunteers who dedicate themselves to creating this safe space. Ross just wasn’t that kind of person. His interest was in organizing. So once the UFW orchestrates some pretty nasty moves to keep farm worker leaders from rising in power within the union, there’s not much for Ross to do at that point.

What’s interesting about this is he held everyone else accountable except Cesar. So one theory is that he felt like his legacy was too tied up with Cesar’s and that if he criticized Cesar in some way, he’s criticizing himself.

I don’t quite buy that. Ross and Chavez had been through the trenches together, they had a deep relationship. Even though they didn’t talk a lot in their later years, Ross had propped Chavez up and was really a voice of encouragement when Chavez was doing what seemed like an impossible dream, leaving a good job to go try and start a farm workers union that’s never really worked before. So I think if he criticized Cesar publicly, that would have been the end of their relationship. When people criticized Cesar it was like done. I’m not sure when Ross was in his 70s, he’s ready for that or he wants to do that.

What would Ross think of the huge challenges the labor movement faces today?

He would be excited about the fact that unions, maybe only because they’re pushed up against the wall, are becoming much more experimental, taking more risks.

If you want to be super Ross-ian and optimistic about this, the fact that labor unions have tried other things for so long and have been shrinking, that opens up a space to take more risks and to do these kind of one-day strikes and things that just haven’t been done. Part of that comes out of the Occupy spirit too, a bit. This Fight for 15 doesn’t look like anything that we’ve seen for a while in the labor movement.

You must have, in the course of writing this book, come across all sorts of interesting strands that you didn’t have time to pursue. What’s your next project?

I’m doing an oral history book of California farm workers for a publication called Voice of Witness started by Dave Eggers, out of San Francisco. I will be traveling the state interviewing farm workers, kids of farm workers, advocates. They tell their stories in their own words. The main purpose is to allow it to get to the consumers so they get a better sense of who the folks are that are making their salads possible or getting the fruit to their table.

-

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026Amid the Violent Minnesota Raids, ICE Arrests Over 100 Refugees, Ships Many to Texas

-

Featured VideoFebruary 4, 2026

Featured VideoFebruary 4, 2026Protesters Turn to Economic Disruption to Fight ICE

-

The SlickFebruary 2, 2026

The SlickFebruary 2, 2026Colorado May Ask Big Oil to Leave Millions of Dollars in the Ground

-

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 5, 2026

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 5, 2026Lawsuits Push Back on Trump’s Attack on Child Care

-

Column - California UncoveredFebruary 6, 2026

Column - California UncoveredFebruary 6, 2026What It’s Like On the Front Line as Health Care Cuts Start to Hit

-

The SlickFebruary 10, 2026

The SlickFebruary 10, 2026New Mexico Again Debates Greenhouse Gas Reductions as Snow Melts

-

Latest NewsFebruary 12, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 12, 2026Trump Administration ‘Wanted to Use Us as a Trophy,’ Says School Board Member Arrested Over Church Protest

-

Latest NewsFebruary 10, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 10, 2026Louisiana Bets Big on ‘Blue Ammonia.’ Communities Along Cancer Alley Brace for the Cost.