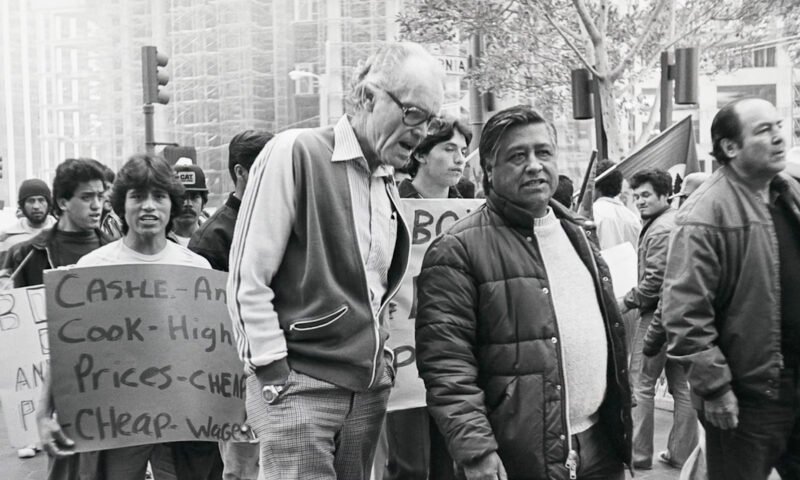

A new documentary about Cesar Chavez’s mentor offers lessons for activists in dark times.

An innovative organizer for three unions, Ross also challenged U.S. policy toward Central America.

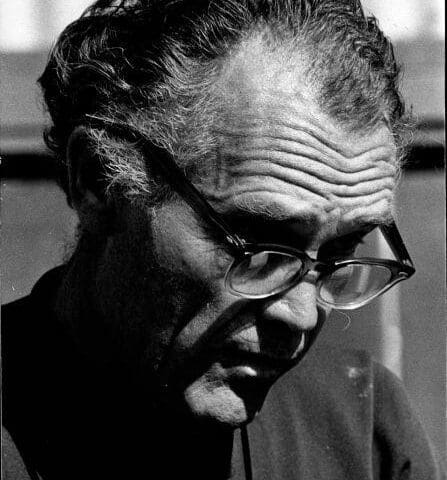

Sometimes the most interesting, and influential, figures in history are anything but household names. A case in point is Fred Ross, one of the greatest organizers of the 20th century.

The police stop a young man. An officer shoots, killing him. The officer claims self-defense, that the killing was warranted.

The community, having endured years of unequal treatment at the hands of law enforcement and other municipal agencies, responds in anger. Protests ensue. Hard feelings persist, as do demands for law-enforcement accountability.

Sound familiar? No, this is not the case of 18-year-old Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri. The young man in question was Augustin Salcido, 17, and the incident occurred in Los Angeles more than six decades earlier. The Internet did not exist at that time and local television audiences were miniscule, so the Civil Rights Congress of Los Angeles produced a pamphlet, Justice for Salcido. In its introduction, author and civil rights advocate Carey McWilliams described the killing as part of a historical pattern of “continued suppression of the Mexican minority.”

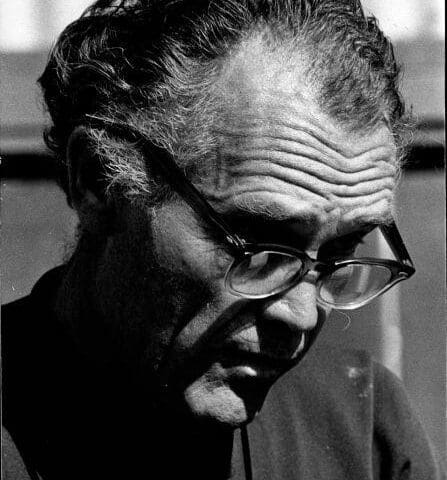

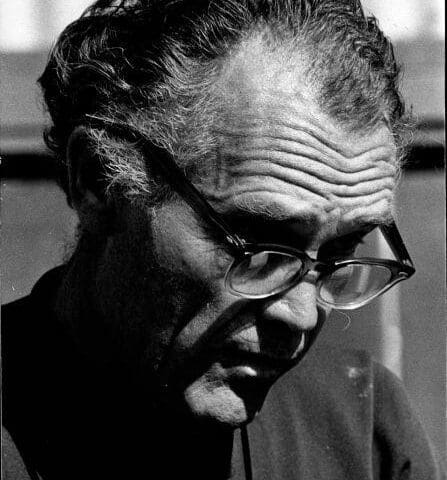

Fred Ross,

» Read more about: Fred Ross, Cesar Chavez and Lessons for Ferguson »

California State Senator (and former United Farm Workers activist) Bill Monning is sponsoring an effort on behalf of a broad coalition of activists and legislators urging Governor Jerry Brown to nominate Fred Ross Sr. for the California Hall of Fame. Ross, who mentored Cesar Chavez, Dolores Huerta, Eliseo Medina and multiple generations of great activists, was arguably the leading community organizer of his time. Although Ross died in 1992, his influence over current Latino voter outreach and labor organizing strategies remains strong. A national campaign began earlier this year to get President Obama to award him the posthumous Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Fred Ross Sr. spent 60 years in California working to bring social and economic justice. But he is not in the state’s Sacramento-based Hall of Fame, an omission that Senator Monning and others now hope Governor Brown will remedy.

On September 6, 2013, Monning, along with Senate leader Darrell Steinberg and many of their Senate colleagues,

» Read more about: Fred Ross Sr., California Hall of Fame Candidate »

Activists, organizers and elected officials across the United States have come together to urge President Barack Obama to award posthumously the Presidential Medal of Freedom to the legendary organizer, Fred Ross Sr. The first to organize people through house meetings, a mentor to both Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta, and a pioneer in Latino voter outreach since 1949 when he helped elect Ed Roybal as Los Angeles’s first Latino council member, Ross’ influence on social change movements remains strong two decades after his death in 1992. If there were a Mount Rushmore for community organizers, Ross’s angular face would be on it. Here is a brief summary of Ross’s remarkable legacy, along with instructions on how to get your message of support to President Obama in time for the February 28 deadline.

Like all activists familiar with his work, I had a reverence for Fred Ross, Sr. before I knew the full record of his accomplishments.

Fifty years ago I graduated from high school on the other side of town from where Dolores Huerta had a decade earlier. My high school class will hold its reunion this fall. Also 50 years ago, Huerta and Cesar Chavez founded the United Farm Workers a few miles further south in Delano. The UFW just celebrated its half-century at its annual convention, this year in Bakersfield.

Long before I met Chavez I had heard of the legend. He had learned about organizing under Fred Ross, who was criss-crossing the state building the Community Service Organization (CSO) network among the Spanish-speaking urban barrios. But when Chavez wanted to expand CSO’s mission to organize farm workers in the Central Valley, CSO said no. So he did it on his own, with no money, no budget and only a handful of contacts. He went to Delano and began to work among the vineyards,

» Read more about: Fields of Dreamers: Looking Back at the UFW »