John Deasy is gone. According to City News Service, the Superintendent of Schools for the Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD), “submitted his resignation today, ending his three-year tenure as head of the nation’s second-largest school district. Although he is stepping down as superintendent, he will remain with the district on ‘special assignment’ until Dec. 31.”

Deasy’s resignation letter, posted on LAUSD’s website, concludes:

I will transition from this job to another way to serve. In allowing me to do that, I hereby submit my resignation. I will work with your council to close out my employment contract.

In closing, let me thank my critics, for they have helped us see where we can do our work better, and that is what we do with each opportunity to improve. I also wish to thank my supporters. You have enabled us to move quickly to right wrongs in the lives of youth,

» Read more about: School’s Out for LAUSD Superintendent John Deasy »

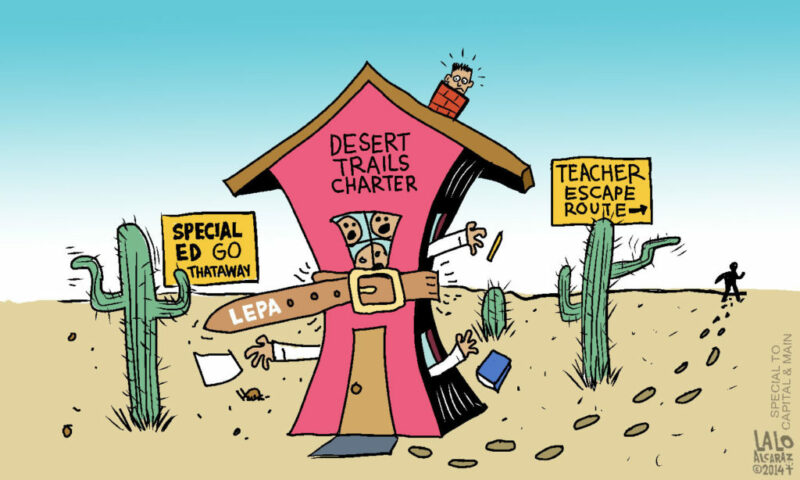

Throughout 2011 and 2012, the eyes of the education world were focused on Adelanto, a small, working class town in California’s High Desert. A war had broken out there over the future of the K-6 Desert Trails Elementary School and its 660 low-income Latino and African-American students. When the dust settled, Desert Trails Elementary was gone. In its place was a bitterly divided community and the Desert Trails Preparatory Academy, the first (and so far, only) school in California and the U.S. to be fully chartered under a Parent Trigger law, which allows a simple majority of a school’s parents to wrest control of a low-performing school from a public school district, and transform it into a charter school.

Tiny Adelanto’s turmoil reflects a much larger battle now being fought across America between defenders of traditional public education and a self-described reform movement whose partisans often favor the privatization and deregulation of education.

» Read more about: Adelanto Report Card: Year Zero of the Parent Trigger Revolution »

Whether or not Parent Trigger represents a bold frontier in the movement to privatize the nation’s public education system, its implementation in California’s High Desert does bear some of the freewheeling aspects of the old Wild West.

Particularly when it comes to accountability and due process. Where do parents or teachers blow the whistle if they suspect a charter school is violating education code or the promises made to students in its own chartering language?

In California, the chartering school district has the statutory authority, and arguably the responsibility, to investigate violations of the law and of the school’s charter. Under Education Code §47607, it may revoke a school’s charter if the school violates the law or violates the conditions set forth in its charter.

Eight former Desert Trails teachers have emphasized to Capital & Main that it was only after frustrated parents told them that Parent Revolution said they were on their own in working out any grievances directly with Desert Trails that the teachers stepped in and took their own allegations of code and charter violations to the school’s chartering authority,

“Am I stutterin’, son?” the green-eyed pleasant-looking man with the perfect teeth said to the tall newcomer standing by his table. Around them the din of the eatery seemed to recede. “There’s no DeMarkus around here.” Like his displeasure, Teaflake made no effort to hide the butt of the Glock sticking out of his waistband.

The young woman sitting with Teaflake smiled understandingly, like she was ushering a patient in for a tooth extraction, Joseph “Little Joe” Dixon reflected.

“Didn’t mean nothing,” he said. “Heard you two was boys is all.” He wasn’t about to back down but wasn’t looking to escalate matters either.

“Who are you?” Teaflake said, his voice low, his enunciation clear and concise, a sharp contrast to the way the usual street hoodlum swallowed vowels and ignored tenses.

Little Joe said, “I’m the new fitness director at Water Stones.” The multi-purpose center was Waterston but everybody called it by its mangled nickname.

OAKLAND – The growing nationwide movement by cities and counties to raise the minimum wage is currently centered here in the Bay Area, and its success couldn’t be more urgent for workers like John Jones III.

Jones, 40, is a licensed aircraft mechanic but works as a Burger King security guard in downtown Oakland, making $10 an hour — $1 more than California’s minimum wage. His life is a series of financial challenges and daily indignities as he struggles to support his wife D’Nita, his 12-year-old son Kai and his newborn boy, Josiah.

To take a shower in his apartment, Jones has to use pliers to turn on the water because the knobs are broken. He can’t complain to his landlord because he’s behind on the rent. When his family runs out of toilet paper, Jones cuts paper towels into quarters to save a few bucks. He covers the windows in his bedroom with blankets because he can’t afford curtains.

» Read more about: Bay Area Cities Set Sights on Raising Their Minimum Wage »

I’m currently taking an Occidental College class called Community Organizing – a required class for my Urban and Environmental Policy major. We’ve spent the last couple of weeks learning about what it means to bring about change – the planning that needs to go into it, the necessary time commitment, the different levels of power you need to take into account.

To be completely honest, I’m still figuring out whether I consider myself an activist. Am I someone who is engaged in bringing about change? I’m not sure.

That’s when I had the opportunity to interview a modern-day community organizer and change-maker: Pastor Norma Jean Patterson.

She made it clear that life-changing community organizing continues today, and made the historic leaders we talked about in class much more tangible in my mind. In the hour she spoke, she did more than just tell me her story, she moved me to understand the simpler concept underneath all the issues of community organizing: the power of loving people.

» Read more about: Community Organizing: Making it Real, from L.A. to East St. Louis »

Dino Degrassi and Jason Campbell engage in dialogues for a living. They also put the electrical wiring into some of Los Angeles’ largest and most recognizable building projects. Every morning at 6:30 the two electricians ride the street level elevator down into the construction site at Wilshire and Figueroa, where the core of the Wilshire Grand hotel is emerging out of the ground. When finished, the 73-story building will be the tallest west of the Mississippi.

Degrassi is a seasoned journeyman – ostensibly a teacher of apprentices like Campbell who work their way through a five-year program, learning as they go.

Throughout the day, the men’s hard-earned craft knowledge guides their conversation. “I try to help Jason work efficiently,” Degrassi says, as he moves along a cement deck tying in conduit. “I want to make sure he paces himself and doesn’t get hurt.”

“There’s a lot of wisdom to be learned from Dino,

» Read more about: Let’s Talk – Socrates at the Wilshire Grand »

Seventy-three percent of polled Americans believe that corruption in government is widespread. That’s a lot of distrust. And it leads to a lot of cynicism. A big chunk of that corruption comes from the revolving door of politics, greased by money so great it would make most of us faint-of-heart.

Seventy-three percent of polled Americans believe that corruption in government is widespread. That’s a lot of distrust. And it leads to a lot of cynicism. A big chunk of that corruption comes from the revolving door of politics, greased by money so great it would make most of us faint-of-heart.

Pols move from elected office to big offices on Wall Street or to lobby firms in state capitals across the nation. Government regulators have often left the very industry they are charged with regulating to join a commission in the sector they are supposed to regulate. Later, they return to the same business they once worked for.

Of course these people are not making decisions in the best interest of the consumer, since even when they are on the government payroll they carry the acute awareness of soon returning to that corporate office. They want to regulate without annoying too many future employers.

At some point during the last decade, as various plans have been floated to avert climate change, it struck me that we’re focusing on the wrong problem. Global warming caused by a buildup of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere (carbon dioxide chief among them), has indeed sped us in the direction of rendering the planet uninhabitable for life, human and otherwise. But climate change is not a disease in itself. Instead, it’s a symptom of a disease, systemic and pernicious, brought on by squandering the parts of nature we call “resources” at a breathtaking clip and without restraint. All of the solutions on offer, from displacing coal with natural gas in the West to constructing more nuclear reactors in the South, are supposed to allow us to go living exactly as we do, without the consequences.

Except we can’t. As Naomi Klein, author of No Logo and the blockbuster bestseller, The Shock Doctrine,

» Read more about: Reviewed: Naomi Klein’s “This Changes Everything” »

Detainees at the Northwest Detention Center, an immigrant detention center operated by GEO Group in Tacoma, Washington, initiated the first of repeated hunger strikes on March 7, 2014. A note from one of the hunger strikers passed to his lawyer read, “Please contact the local news. There’s 1,200 people not eating—better food, better treatment, better pay, lower commissary, fairness.”

Detainees at the Northwest Detention Center, an immigrant detention center operated by GEO Group in Tacoma, Washington, initiated the first of repeated hunger strikes on March 7, 2014. A note from one of the hunger strikers passed to his lawyer read, “Please contact the local news. There’s 1,200 people not eating—better food, better treatment, better pay, lower commissary, fairness.”

The story of the hunger strikers is documented in a new report released by Grassroots Leadership and Justice Strategies detailing how immigrants detained in privately run detention centers across the country are routinely exposed to shocking levels of violence, sexual abuse, neglect, filth and wrongful death.

The report titled For-Profit Family Detention: Meet the Private Prison Corporations Making Millions By Locking Up Refugee Families, exposes how Corrections Corporation of America and GEO Group are both banking on a massive expansion to immigrant family detention.

» Read more about: Lowering the Bars for Humane Prison Conditions »