Governor Jerry Brown signed Assembly Bill 1897 into law Sunday, inaugurating what the bill’s author, Roger Hernandez (D-West Covina) described as “landmark legislation . . . to protect hard-working Californians who often times do not have a voice in the workplace.” The bill was drafted in response to the growing practice of corporations, particularly agriculture-based companies, to skirt state labor laws by relying on third-party contractors to hire employees and administer their wages.

Last May a Capital & Main report by Bill Raden and Gary Cohn documented how workers at the sprawling Taylor Farms vegetable and salad processing plant in Tracy were denied due-process rights along with health care and other employee benefits. (See “Ten Years a Temp: California Food Giant Highlights National Rise in Exploited Labor.”) Taylor Farms has claimed that workers at its facilities are temporary employees who work for various contracting outfits. Many of these employees have worked years for Taylor Farms and yet have had little chance for advancement.

» Read more about: Governor Brown Signs Employer Accountability Law »

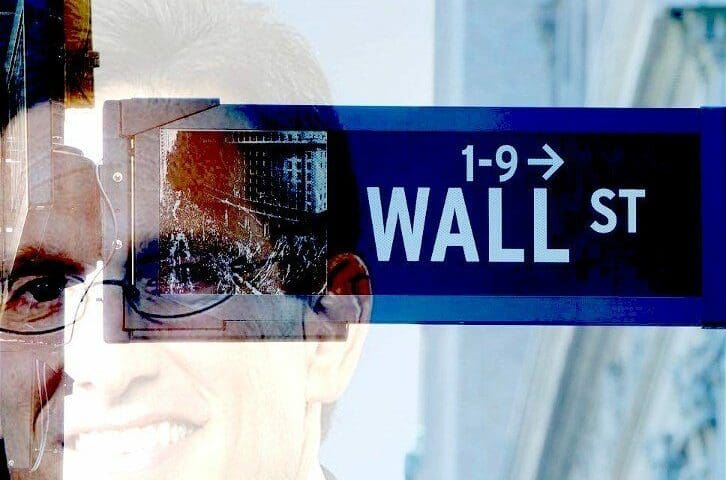

When House Majority Leader Eric Cantor lost his primary bid for re-election, he wasted no time cashing in on new opportunities. He didn’t even wait for his term to end before resigning his office August 18 – leaving his constituents unrepresented for three months, and making the leap to big bucks on Wall Street. His base pay in his new position with the investment firm Moelis & Co. is $400,000 for the remainder of the year, plus a $400,000 signing bonus. He also gets a million dollars-worth of restricted stock – altogether about 26 times the average income of Virginians in his old district.

What makes an ex-Congressman so valuable to an investment firm based in New York City? To be clear, he cannot return to the floor of the House to lobby his former colleagues on a bill. Congress ended that practice in the middle of the last decade.

» Read more about: The Big Money: Eric Cantor Goes to Wall Street »

I was inspired by the videos and photos of the more than 300,000 people at the People’s Climate March this past weekend in New York. The word is out, climate change is real, but what people might not know is the privatization of American infrastructure is contributing to the problem.

In a joint article with Professor Stephanie Farmer, I detail how poorly structured “public-private partnerships” (P3s) hinder efforts by cities and states to address climate change.

The city of Chicago is learning this the hard way. Not only has the decision to lease the city’s parking meters to a Morgan Stanley-led consortium been a costly mistake for taxpayers (the meters were sold $1 billion dollars under their value), Dr. Farmer’s research has also found that the deal is tying the hands of transportation planners in their efforts to construct environmentally sustainable transportation modes—such as bike lanes,

» Read more about: How Privatization Contributes to Climate Change »

It sounded like a moment from a Chris Rock comedy: A bewildered black motorist writhes on the ground in pain, asking, “What did I do, sir?” of the white police officer who has just shot him at a gas station in broad daylight.

“I just got my license – you said, ‘Get your license’!” exclaims the wounded Levar Jones, who only seconds before had his arms raised in the air. “Why did you shoot me?” The South Carolina Highway Patrol officer matter of factly replies, “For a seatbelt violation.”

The incident, of course, was no comedy or part of a Hollywood movie, but was recorded in the city of Columbia by the officer’s dashboard camera. It took place September 4, although the video only surfaced yesterday. It shows the officer firing four shots at the driver who had been standing beside his pickup truck, when he turned to his vehicle to retrieve his license.

» Read more about: Video Captures Another African American Shot By Police »

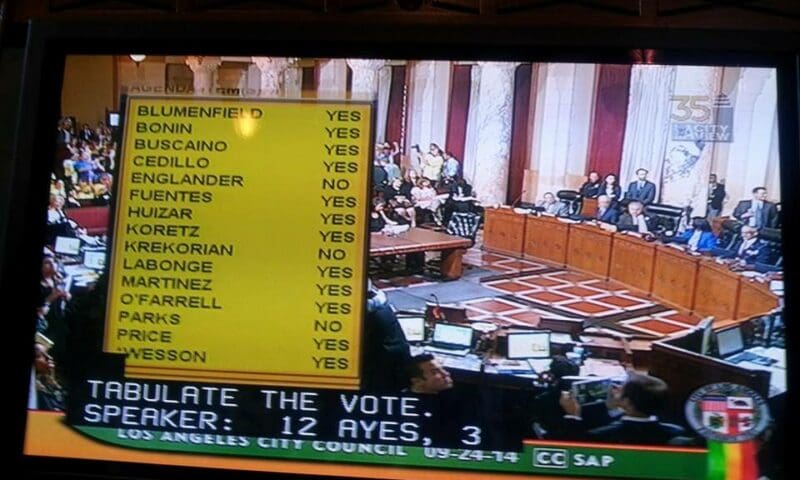

Amid cheers from labor and community supporters, 12 of the 15 Los Angeles City Council members voted Wednesday in favor of an ordinance that will raise the minimum wage for workers in large hotels to $15.37 per hour. The measure will apply to hotels with 300 rooms or more beginning in July 2015, and expand to hotels with 150 or more rooms one year later.

Prior to the meeting an eager crowd of activists and workers, dressed in yellow “Raise LA” T-shirts, gathered in the hall outside the chamber. Raise LA is the name of the movement behind the measure. After the item was introduced, councilmembers offered their views on the living wage ordinance. Councilmember Mike Bonin opened the comments with a statement about economic justice.

“A great unfairness is that people work full time for wages that do not bring them above the poverty line,” he said.

Members of the public then addressed the council,

» Read more about: L.A. City Council Passes Landmark Hotel Wage Ordinance »

The Los Angeles City Council today voted to raise the minimum wage for workers employed by the city’s largest hotels. According to City News Service:

The council voted 12-3 to approve the minimum wage, with council members Bernard Parks, Mitchell Englander and Paul Krekorian dissenting. Because the decision was not unanimous, the issue will come back for a final vote Oct. 1. If approved, hotels with 300 or more rooms would need to start paying the $15.37 minimum wage by July 1 and those with at least 150 rooms would have to comply by July 1, 2016.

Capital & Main will post a detailed story of the historic vote later today.

» Read more about: L.A. Hotel Wage Hike Passes City Council »

The police stop a young man. An officer shoots, killing him. The officer claims self-defense, that the killing was warranted.

The community, having endured years of unequal treatment at the hands of law enforcement and other municipal agencies, responds in anger. Protests ensue. Hard feelings persist, as do demands for law-enforcement accountability.

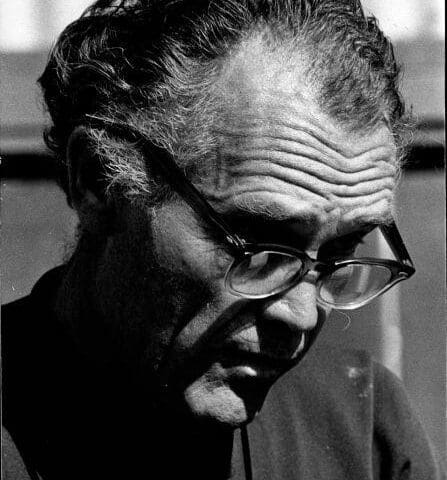

Sound familiar? No, this is not the case of 18-year-old Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri. The young man in question was Augustin Salcido, 17, and the incident occurred in Los Angeles more than six decades earlier. The Internet did not exist at that time and local television audiences were miniscule, so the Civil Rights Congress of Los Angeles produced a pamphlet, Justice for Salcido. In its introduction, author and civil rights advocate Carey McWilliams described the killing as part of a historical pattern of “continued suppression of the Mexican minority.”

Fred Ross,

» Read more about: Fred Ross, Cesar Chavez and Lessons for Ferguson »

Thousands of low-wage workers in Los Angeles are poised to receive a substantial pay bump, depending on a critical City Council vote scheduled for Wednesday. On the table: a $15.37 hourly wage for hotel employees at some of the biggest and most lucrative non-unionized hotels in the City of Los Angeles.

In June a Los Angeles City Council committee directed city staff to draft an ordinance that would require hotels with 300-plus rooms to meet a $15.37 hourly wage benchmark by July 2015. Hotels with more than 125 rooms would have to meet the standard in 2016. The full council is expected to take up the proposal Wednesday morning after a Tuesday hearing at the Economic Development Committee.

Business interests complain that the measure would cost jobs, but proponents argue that tourism and the hotel industry are experiencing record growth and creating local jobs. A study prepared by the Economic Roundtable,

For Americans today – particularly for bloggers, Senators, reporters and activists — it’s pretty much always a definitive rebuke to accuse someone of “acting politically.” Reflexive disdain for political motives is deeply rooted in our popular culture, which so often assumes that ethics is one thing, politics quite another. “You quit a profession you love for ethical reasons,” the President tells the main character on CBS’s Madam Secretary. “That makes you the least political person I know.”

But however culturally pervasive and recognizable this kind of disparagement may be – however tempting it is to call out someone for their political motives — there are reasons to do so sparingly.

To see why, it’s worth reflecting on two of the most striking recent instances in which base political motives have been alleged. Both the right and left agreed that Barack Obama’s decision to postpone executive action to reduce deportation of undocumented immigrants was unprincipled and political.

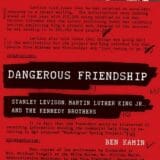

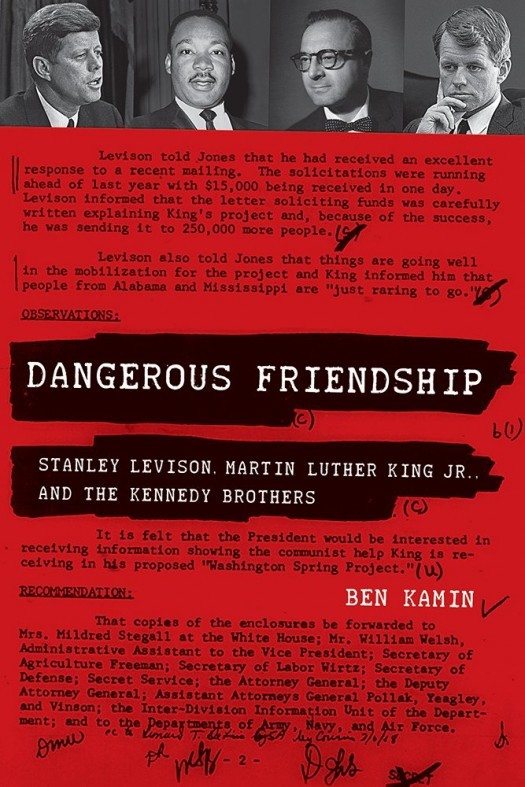

FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover tried to erase the name of Stanley Levison from civil rights history in the 1960s. Now historian Ben Kamin is putting Levison firmly back into the historic record with his new book, Dangerous Friendship: Stanley Levison, Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Kennedy Brothers.

FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover tried to erase the name of Stanley Levison from civil rights history in the 1960s. Now historian Ben Kamin is putting Levison firmly back into the historic record with his new book, Dangerous Friendship: Stanley Levison, Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Kennedy Brothers.

Levison was a successful Jewish businessman and member of the American Communist Party until 1956, when the Soviet invasion of Hungary left him disillusioned. He refocused his organizing skills, business and labor contacts, energy and intelligence to support the work of Martin Luther King Jr., helping to found, manage and fund King’s organization, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. In the process, Levison became an intimate friend of King and part of the tight circle of confidants who helped develop King’s campaigns and sustain him emotionally.

What drew Levison, and hundreds of other American Jews like me,

» Read more about: Book Review: MLK’s Dangerous Friendship »