Proposition 60’s decisive, 54-46 percent loss was equal parts surprising and depressing to its backers, particularly the Hollywood-based AIDS Healthcare Foundation, which had put the initiative on the ballot.

California voters on Tuesday approved state Proposition 56 by an overwhelming 63-37 percent margin to create a new excise tax of $2 per pack on cigarettes and other tobacco products. The margin of victory was a shock: Similar ballot initiatives failed in 2012 and 2006, and tobacco companies spent $71 million to blitz the state with dramatic advertising urging a No vote.

With financial backing from law enforcement groups, the California death penalty is not only preserved, but will be sped up for inmates awaiting execution.

On Tuesday California said no to the plastics lobby’s wish list. Proposition 67 passed with 52 percent affirming the law banning the bags. Proposition 65 failed, with 51 percent rejecting the redirection of bag fees. It was precisely the result environmental groups, grocers and unions had pushed for.

The avalanche of money that rolled in from pharmaceutical drug companies to beat back the challenge to their bottom lines posed by Proposition 61 dwarfed the money contributed to the Yes on 61 effort, which still ran into the millions.

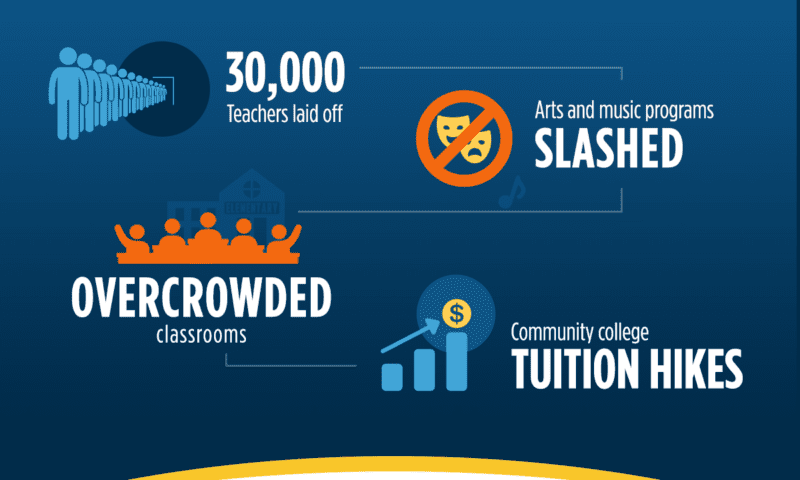

Victorious Proposition 55 has extended a policy initially approved by Californians in 2012 to make up the recession-era budget cuts in the Golden State—cuts that devastated spending on education and health care. The 2012 measure, Proposition 30, established a personal income tax increase on household incomes of $250,000 and above.

Most initiatives that appeared on the California ballot passed this Tuesday, but not everyone came away a winner. Capital & Main presents our writers’ analysis of what happened to eight key ballot measures – and why.

Yesterday the subscriber-only political almanac California Target Book reported that spending by all independent expenditure committees (IECs) on legislative races in the general election had topped $41 million. That brought the year’s total of outside money for state Assembly and Senate seats, including primary races, to $70 million.

With a wink to Thomas Hobbes, this year’s election season has been nasty, brutish and long. Today it comes to an end, allowing us to look back on some of Capital & Main’s best reporting on issues that affect Californians on the most fundamental levels.

“This could be the shot heard round the world!” Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders told a Los Angeles rally held Monday in favor of Proposition 61. About 650 office workers, health-care activists and California nurses gathered that morning in Pershing Square to support the drug pricing initiative.