More than a third of Americans are showing signs of clinical anxiety or depression, a 300 percent increase over last year.

What is the connection between a lack of commitment to collective well-being and social disaster in a time of crisis?

Co-published by The Guardian

For the full story read Mark Kreidler’s “Industry Seeks to Flatline Universal Health Care.”

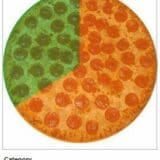

Test your knowledge about inequities in America’s health care system.

Co-published by Truthout

Undocumented immigrants fear that seeking medical care will get them kicked out of the country. One woman’s story shows the impact can prove deadly.

Co-published by the American Prospect

Diseases don’t respect borders, nor do they care about passports, citizenship or residency.

How can the new administration best help California’s neediest residents?

Dr. Coley King, director of homeless services at Los Angeles’ Venice Family Clinic, explains how multidisciplinary teams work in preparing homeless people for a better life.

Co-published by International Business Times

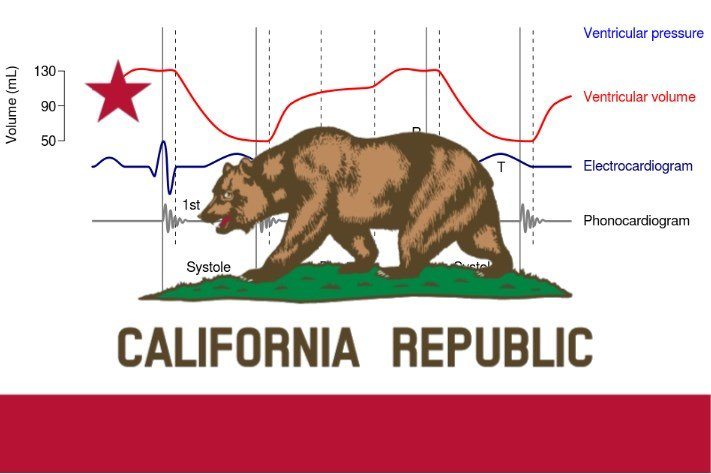

State leaders are realizing that California must play both defense and offense to preserve and expand its health-care gains, and to protect vulnerable groups – particularly the state’s huge immigrant population.

“Right now, I have a medicine sitting at Wal-Mart pharmacy that I can’t purchase till payday,” Jacqueline, a 55-year-old San Diegan told me during a telephone interview in mid-April. She asked that her last name not be used for this story. “I’ll go without, eight or nine days till payday. It’s for my high cholesterol.”

Five years after the Affordable Care Act became law, and more than three years after California began moving aggressively to implement its provisions, upwards of three million Californians remain without health care coverage; and millions more, like Jacqueline, have basic coverage but continue to be grievously under-insured.This is the story of how so many Californians continue to fall through the ACA’s cracks.

“Uncovered California” is a three-part series of stories and videos examining how the Golden State is trying to fill holes in its health care coverage. Sasha Abramsky’s articles look at working people who are falling through coverage cracks,

» Read more about: Uncovered California: Why Millions Have Fallen Into Health Care Gaps »

The next step in deciding whether California will join other state efforts to demystify the drug pricing practices of pharmaceutical manufacturers will be taken tomorrow as the Assembly’s Health Committee votes on a drug pricing transparency bill introduced in February by State Senator Dr. Ed Hernandez.

More than 5,000 registered nurses belonging to the California Nurses Association (CNA) are striking today at eight California hospitals, with a somewhat smaller number continuing the strikes Friday. The nurses are demanding that hospitals provide adequate staffing levels which are now, they claim, endangering patients. (Disclosure: CNA is a financial supporter of Capital & Main.)

Hospitals affected by the strike are: Los Angeles Medical Center (Kaiser Permanente); Providence Little Company of Mary Medical Center Torrance; Providence Saint John’s Health Center; Mills-Peninsula Health Services (Sutter); Sutter Auburn Faith Hospital; Sutter Roseville Medical Center; Sutter Santa Rosa Regional Hospital and Sutter Tracy Community Hospital.

Sue Robbins, a registered nurse who has worked at Sutter Roseville Medical Center for 14 years, says this is her first strike and it’s also the first time a strike has taken place at her hospital, located north of Sacramento.

Robbins says that a rehab center that served the community is gone and that Sutter’s management wants to eliminate “baby nurses” —

» Read more about: Nurses at Eight California Hospitals Strike to Demand Adequate Staffing »

As Sacramento shifts into its August overdrive this week, three key health care reforms have been attracting fierce lobbying attacks by business interests and the hospital and health insurance industries, to keep them from advancing out of the Senate Appropriations Committee for floor votes. August 31 is the deadline for the full Assembly and state Senate to pass any bills destined for the governor’s desk.

AB 1522, known unofficially as the Healthy Workplaces, Healthy Families Act, was introduced by Assemblywoman Lorena Gonzalez (D-San Diego) with the support of the California Labor Federation. It would make California, after Connecticut, the second state to require employers to provide paid sick leave for all of its workers. (The California Labor Federation is a financial supporter of Capital & Main.)

AB 503, the proposed hospital charity care law, introduced by Assemblymen Bob Wieckowski (D-Fremont) and Rob Bonta (D-Oakland),

» Read more about: Three Bills Aim to Strengthen California’s Health Care System »

Every year Los Angeles’ Cedars-Sinai Medical Center releases a glossy brochure called Report to the Community. Among the doctor profiles and research-breakthrough stories are several dry metrics dealing with the number of beds, total patient and outpatient days and, perhaps most impressively, the year’s dollar value for something called “community benefit contributions.”

Cedars, which is the state’s third highest-earning nonprofit hospital, claimed $640.3 million as its 2012 community benefit contribution.

This number turns out to be the real point of the report. Because under state law all not-for-profit hospitals must justify their continuing tax exemption as charitable institutions by demonstrating that they are providing a community benefit — free charity care to indigent patients and what California calls “activities that are intended to address community needs and priorities primarily through disease prevention and improvement of health status.”

Whether Cedars and California’s other nonprofit hospitals have been living up to that charitable obligation is a question that Assembly Bill 503,

» Read more about: Sweet Charity: The Truth Behind Hospitals’ Community Benefits Windfall »

My cousin and I have stayed in touch over the years despite the distance — he grew up in a Texas border town and has lived his adult life in Phoenix. Both he and his wife have held well-paid positions in the health field. Like most families, when we visit, we avoid subjects in-laws shouldn’t talk about, including politics and religion. But this time, he brought up the topic of unions, so over the next several days we talked intermittently about unions and why low wage workers need them.

On our final evening together, we sat across from each other in one of those expensive Santa Monica restaurants named after its chef. I said, “So here is the bottom line for me: People who work all day should be able to provide shelter and food for their families, and they ought to have health care.”

“I don’t know that I disagree with that,” he replied.

» Read more about: Building a Better Life: Bottom Lines and Top Priorities »

Four years ago, my wife and I planted an oak tree on Election Day – our Obama Oak – at the front of our house. The remarkable thing about the tree is how long it holds on to its leaves. I see it from my window, now doubled in height, still holding its crimson leaves, even after Sandy’s winds blew the leaves off of every other tree in the surrounding Taconic Hills. For me, the Obama Oak’s hardiness is a testament to perseverance of a health reform movement and a president, who together completed the 100-year quest to make health care a government-guaranteed right in the United States. With the president’s reelection, that quest is now secure and a new era in American health care begins.

I am sure that skeptics on the left will scoff at the assertion that the ACA launches a new era in health care. After all, a key to securing congressional passage of the Affordable Care Act was that the law did not upend the current system of health care financing in the United States.

A couple of weeks ago I sat in on a meeting of the leadership of some local hotels. These were not the hotel managers, but the leaders among the workers who clean the rooms, clear the tables, chop the vegetables in the kitchen, vacuum the rugs in the lobby and perform all the other back-breaking tasks that make a hotel comfortable for guests.These people – all from hotels with union contracts – face tough negotiations going into the fall and their workplaces could face serious competition from several proposed downtown hotel projects.

Nearly all these men and women, many of whom arrived wearing the uniforms of their hotels, spoke Spanish. This put me at a serious disadvantage because despite my efforts to learn this beautiful language, I can’t seem to speak it and I can hardly understand the rapid sentences thrown back and forth between people who all know one another and have worked together for years.

» Read more about: Found in Translation: A Union Contract's Strengths »

My grandchildren live on pizza. Oh, they eat other things that young children like, but whenever mom or dad work late or events intervene, the call goes out for pizza man to deliver.

I was thinking about this when I read a piece in The Week a while back about franchisers who will soon need to cover the cost of health insurance for their low-wage workers or pay a fine. The case study focused on a guy who owns a string of chicken and Mexican fast food stops and who employs 425 workers. Some of these people run the front counter. Some do the deep frying. Some sweep up. None, apparently, have any health insurance.

The owner complains that providing these workers health insurance will cost him $546,000 a year – a cost that he says his business plan simply cannot support. Really? I thought.

» Read more about: Pizza, Health Care and the Minimum Wage »