Featured VideoOctober 30, 2025

What It’s Like to “Self-Deport.”

By Jeremy Lindenfeld

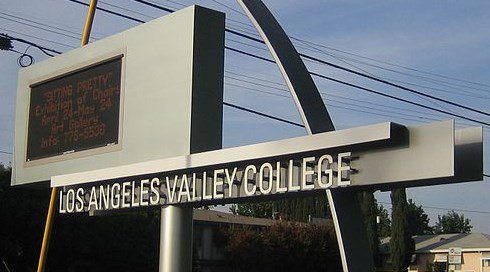

Juan González, an undocumented immigrant from Mexico, lived in Pasadena for three decades before a wildfire, heart attack and ICE raids got him thinking about “self-deporting” back to Mexico.