Randy Shaw does not fit the rabble-rouser profile. An upper-middle-class native of West Los Angeles, he came to San Francisco in 1979 to enroll in the city’s prestigious Hastings Law School, whose downtown campus is part of the University of California, Berkeley. There, however, he discovered that his school had for years been expanding by swallowing up residential hotels catering to low-income residents in the adjacent Tenderloin district.

“It used to be,” Shaw remembers, “that if you wanted to evict someone in the Tenderloin you’d throw them down a flight of stairs. Then it became more civilized: You’d just threaten to throw them down a flight of stairs.” In 1980 he co-founded the Tenderloin Housing Clinic as a legal aid resource for neighborhood residents. But it soon grew into an aggressive grassroots organization battling developers who wanted to replace much of the Tenderloin with luxury tourist hotels.

The Partnership for Working Families Summit kicked off Tuesday in Los Angeles as activists from around the country convened at the Biltmore Hotel for three days of workshops and talks focused on creating good jobs, sustainable industries and strong unions.

The Partnership includes such groups as the Los Angeles Alliance for a New Economy (LAANE), Puget Sound Sage and the Alliance for a Greater New York (ALIGN). While attendees came from a range of organizations and campaigns, the idea that cities can be platforms for change provided a common thread. As Leslie Moody, the Partnership’s outgoing executive director, put it in her opening remarks, “Cities matter.”

Moody pointed to the new set of progressive mayors taking office across the U.S., but added that elected leaders do not act alone. She cited the way communities have pushed new civic officials to follow through with constructive policies.

“We’re not going to wait for federal change,” Moody said,

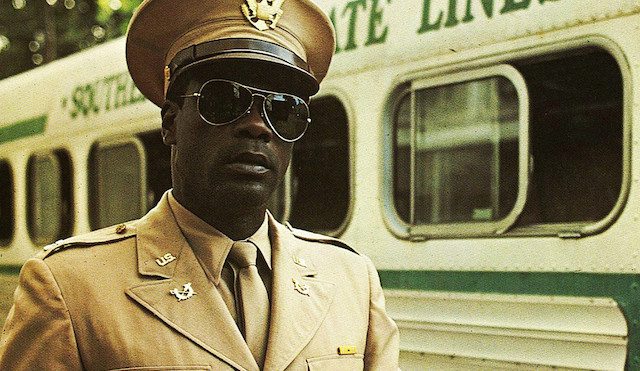

Every year for Black History Month, the TV networks and premium movie channels roll out the same programming: Malcolm X, Mississippi Burning, The Color Purple…. It’s not that these films aren’t great; they are. It’s just that every year for as long as they have been around, they’re all that come on during February. I can quote The Color Purple line for line. The history of black folks is larger and more diverse than the civil rights movement and slavery. Let’s give some other films a shot, shall we?

Let the Fire Burn

In the spring of 1985 a bomb was dropped on a row house in Philadelphia. A fire spread quickly and burned down 61 houses, eventually killing 11 people, including five children, and injuring numerous others. The fire and police departments stood by and did nothing to stop the blaze.

Every January, our state celebrates the work and legacy of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., a hero who sacrificed his life in the fight to end discrimination and poverty in America. In this respect, it seems appropriate that January is also the month when our Governor releases his budget proposal. The State Budget is more than numbers; it reflects our collective priorities and funds what is most important. Sadly, this budget proposal fails to honor Dr. King and his fight for justice. Within the Governor’s proposal are further cuts to critical social service programs. There is no clearer or more tragic example of this disinvestment than our state’s willingness to cut access to state-sponsored child care for low income families. In the name of justice and equality, we ask the Governor to fully fund child care to ensure universal access to all and quality work conditions for providers.

Currently we have more than 300,000 children languishing on waiting lists,

was a time I would eat anything

torn from my body, as a city

recycles its bricks after trauma.

so I would eat the bitter black things,

those brittle wound stones. was a time, torn,

I’d eat anything from my body,

those yellowed bark ridges. a city

recycles gypsum after trauma.

I’d eat anything, pale crescents torn,

those Moor-less swords. after, a city

recycles. green things from my body,

those rotting gems. those sour gray things—

wasted clay. city, after trauma,

recycles its iron, those bones torn

from a city as though—a body:

those swords and bones, gypsum, gems, trauma:

a torn time recycled. a body

as a city, torn into a thing.

Source: The Black Automaton (2009), published by Fence Books.

An award-winning poet, performer and librettist,

Ted Mitchell, the former Occidental College president nominated by the White House to become Under Secretary of Education, is the founder and CEO of NewSchools Venture Fund, a nonprofit whose goal, according to its tax records, is “to transform public education through powerful ideas and passionate entrepreneurs so that all children – especially those in underserved communities – have the opportunity to succeed.”

Judging by a look at the group’s website, another part of its agenda may be to gut the seniority rights and other job protections currently enjoyed by California’s public school teachers.

This week the site began prominently featuring news about the Vergara v. California trial now unfolding in Los Angeles Superior Court. When called for comment, a NewSchools spokesman said Mitchell’s group was taking no position on the case.

“We believe it’s an important case with broad implications for education,” the spokesman said.

» Read more about: Why Is Ted Mitchell’s Nonprofit Pushing Vergara v. California? »

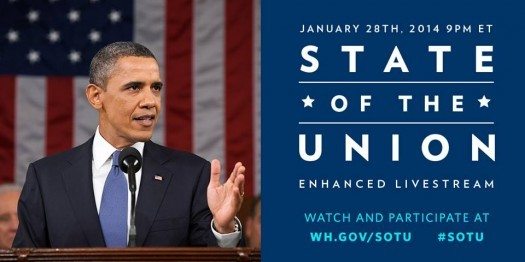

There was something tantalizing about Barack Obama’s State of the Union speech last night. When was the last time an American president talked about the simple human cruelty of our Dickensian sick leave and maternity policies? Or told CEOs to just do the right thing and raise wages for their workers?

What made Obama’s speech compelling is that he did more than just issue platitudes — he announced his decision to use executive authority to increase the pay of workers employed by companies that contract with the federal government. That will mean a nearly $3 an hour raise for hundreds of thousands of people. In an era of Tea Party-engineered partisan gridlock over pretty much everything, that’s nothing less than a seismic shift.

So why didn’t the State of the Union address leave me popping the champagne and toasting to an impending economic realignment that would reverse the nation’s slide back to the same levels of inequality we faced before the Depression?

» Read more about: Obama’s Speech: So Close and Yet So Far »

Lara Bergthold remembers the afternoon she and Norman Lear arrived at Pete Seeger’s rustic home overlooking the Hudson River, a house Seeger and his wife Toshi had built themselves years before. Bergthold, a prominent political and communications strategist and former executive director of the Lear Family Foundation, was the associate producer of Pete Seeger: The Power of Song, a 2007 documentary about the famed folksinger and social activist, and had recently brought Lear into the project. The two had been chauffeured from Manhattan in a Mercedes sedan and were eager to discuss ideas to improve the film that had so far been shot by director Jim Brown.

“When we pulled up to his house,” says Bergthold, “Norman and I get out of the back, and Pete walked around us and to the driver and shook his hand and invited him to come in for salad. He considered the driver to be the person he should greet first and it didn’t matter that the driver was a nameless person.

» Read more about: Pete Seeger Remembered: A Conversation With Lara Bergthold »

Common wisdom says that the subject of economic inequality, while temporarily in vogue, is still a rhetorical minefield. In the half-century since Lyndon Johnson announced the beginning of a war on poverty, presidents have avoided even using the word “poverty,” for fear of turning off voters. And just as perilous as talking about poverty, apparently, is admitting that a policy tries to attack it through “redistribution.” That term, according to the New York Times, is “explosive,” even “toxic,” in America. It’s a word, says William M. Daley, the former Obama chief of staff, that “you just don’t use.”

There’s evidence, however, that many Americans favor a distribution of wealth and income that’s much more egalitarian than the one we have now. But conservatives believe, and not without justification, that many people also dislike the idea of government taking from some people in order to give to others.

» Read more about: Wealth and the Natural Distribution Myth »

Last week, the U.K. publication The Guardian used an interesting anecdote to describe the key finding of an Oxfam report on global inequality: The world’s 85 richest people now own more wealth than the planet’s poorest 3.5 billion people. All of the world’s wealthiest individuals, Guardian writer Graeme Wearden noted, “could squeeze onto a single double-decker” bus.

The ironic image of the super-rich riding a humble public bus is an apt metaphor for the socioeconomic quandary facing America before President Obama makes his 2014 State of the Union address tonight. Underinvestment in job creation, training, education and public services like transportation put middle-class success out of reach for many Americans, while at the other end of the spectrum, wealth has been concentrated in very few hands.

President Obama’s speech ought to address the central problems of economic inequality and deficit of opportunities and services for many Americans.