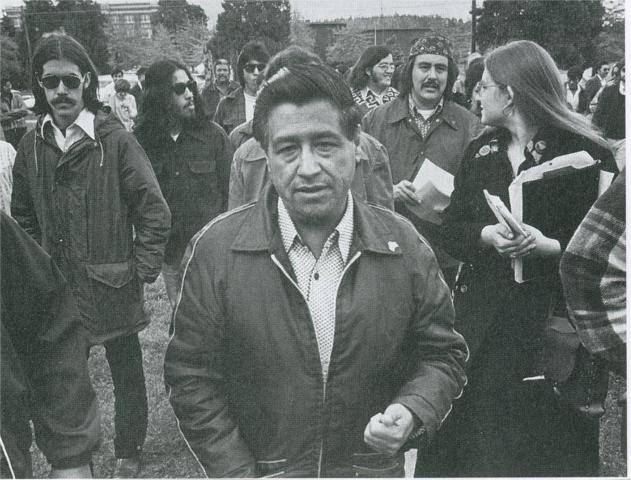

Many people thought Cesar Chavez was crazy to think he could build a union among migrant farmworkers. Since the early 1900s, unions had been trying and failing to organize California’s unskilled agricultural workers. Whether the workers were Anglos, Chinese, Japanese, Filipinos or Mexican Americans, these efforts met the same fate. The organizing drives met fierce opposition and always flopped, vulnerable to growers’ violent tactics and to competition from a seemingly endless supply of other migrant workers desperate for work. So when Chavez left his job as a community organizer in San Jose in 1962 and moved to rural Delano to try, once again, to bring a union to California’s lettuce and grape fields, even his closest friends figured he was delusional.

Within a decade, however, the United Farm Workers (UFW) union had collective bargaining agreements with most of California’s major growers. Pay, working conditions and housing for migrant workers improved significantly.

There haven’t been, to put it mildly, many films about America’s labor movement. Take away Salt of the Earth (1954) and Norma Rae (1979) and what are you left with? Cesar Chavez, then, offers to fill a cavernous void in the public’s knowledge about both union organizing and the history of the country’s mostly Latino agricultural workforce. Directed by the Mexican actor and film producer Diego Luna (Y Tu Mamá También, Elysium), the film follows Chavez (Michael Peña) from the time he parted company with the grassroots Community Service Organization (CSO) to the signing of union contracts with growers following a successful consumer boycott of table grapes.

Working with a screenplay by Keir Pearson, Luna wisely passes on a sweeping Gandhi-style treatment of Chavez’s entire life. This allows Luna and cinematographer Enrique Chediak to linger on the arid poetry of life in California’s Central Valley (played here by Sonora,

When Diego Luna was growing up in Mexico he’d sometimes hear references to Cesar Chavez and the union of farm workers he had organized in America. Luna, who would become one of his country’s leading film stars, remembers being struck as a 13-year-old by television images of Chavez’s funeral – the man was so modest, his coffin was an unpainted wooden box. A few years ago Luna began assembling a production company to film one critical chapter in Chavez’s life – the 10-year period in which he formed the United Farm Workers Organizing Committee and which culminated with the triumph of the consumer grape boycott. Cesar Chavez opens this week and Luna, while in Los Angeles to promote the film, spoke to Capital & Main about the movie, the man and the movement he created.

Capital & Main: Your film is a biography but is there something more behind it?

I think its message is of what we can do when we unite.

» Read more about: Interview With ‘Cesar Chavez’ Director Diego Luna »

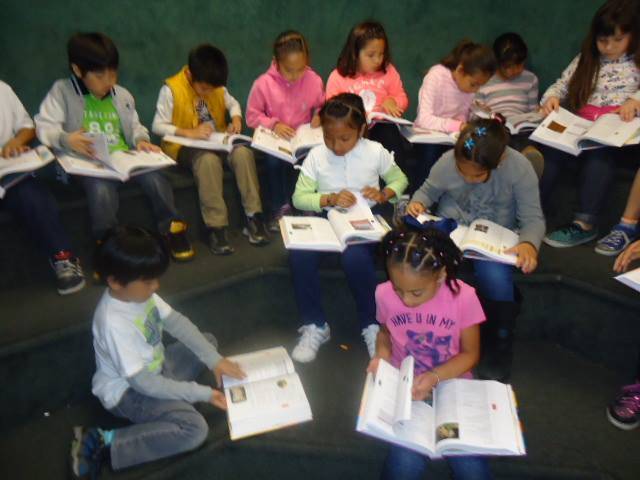

Today in Los Angeles attorneys will offer closing arguments in Vergara v. California, a lawsuit funded by Silicon Valley millionaire David Welch and others with ties to the school privatization movement under the banner of a front organization called Students Matter. The suit wrongly attacks as unconstitutional California statutes covering teacher employment, including the current two-year probationary period, the due process protections built into teacher dismissal and layoff procedures that value experience over more arbitrary factors.

That the probationary period is even an issue is a little mind-boggling; if a principal can have a teacher on staff for two years and still have no idea if that teacher is effective, he or she probably has no business being a principal. At trial, award-winning superintendents and principals have testified that two years is more than enough time to decide whether to keep a teacher on staff and,

» Read more about: Vergara Lawsuit Would Hurt California Students »

When Dan Flaming, the president of the Economic Roundtable research group, describes the tanking of the L.A. economy in the 1990s, he pinpoints the cause to the loss of thousands of aerospace jobs. However, he explains, it was only immigrant migration that rescued Los Angeles financially. The skills, hard work and entrepreneurial energy of the estimated 100,000 immigrants who came here each year between 1989 and 2000 fueled an informal, low wage economy that kept the city humming. (See Flaming discuss L.A.’s present economic climate in the interview above.)

Listen to podcast interview with Dan Flaming

While many people have blamed immigrants for job losses, it was actually the end of the Cold War and subsequent job cuts in aircraft and related industries that led nearly 1.5 million people to leave L.A. for other parts of the U.S.

In their place immigrants arrived and provided work that was completely legal,

» Read more about: Confronting L.A.’s Economy, Past & Present »

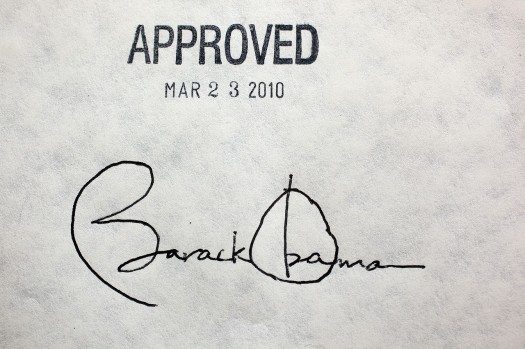

As a writer I bounce from job to job. When not working at LAANE, I have to pay for my own health care – whose monthly premiums, over the past few years, have threatened to surpass my monthly grocery bill. So naturally I was more than glad when the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act – aka, Obamacare – became law in 2010. I know a bit about what it’s like to have and not have health care. My brother was stricken with a rare form of cancer in his early twenties. He survived against some pretty big odds – but only because of my father’s great health insurance, which allowed my brother to be treated at a leading research hospital. I also lived through the height of San Francisco’s AIDS pandemic and saw what uninsured people went through: days spent in hospital waiting rooms, often minimal care, overcrowded rooms and life-threatening delays for medical procedures.

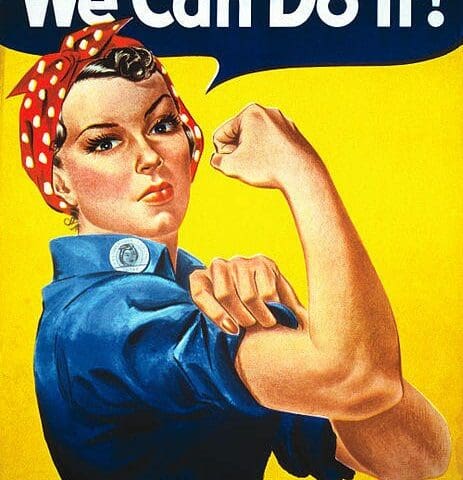

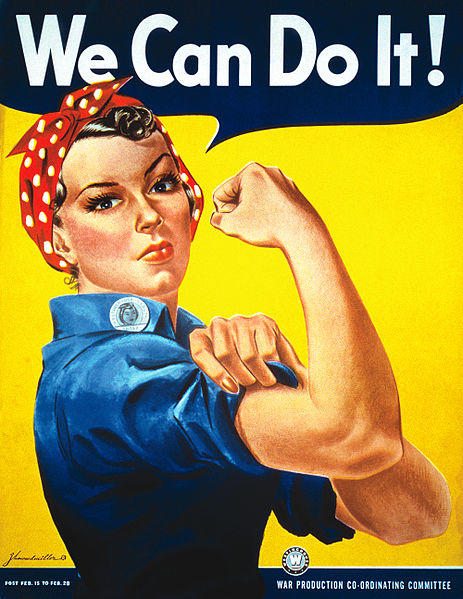

As we celebrate Women’s History Month in March, we honor many iconic women workers from past to present, from Rosie the Riveter to Dolores Huerta. But we often forget about the unsung “sheroes,” the women whose toil and dedication help move America, today.

As we celebrate Women’s History Month in March, we honor many iconic women workers from past to present, from Rosie the Riveter to Dolores Huerta. But we often forget about the unsung “sheroes,” the women whose toil and dedication help move America, today.

One such group is the women workers who manufacture America’s buses, trains and streetcars for our public transit systems. Khanthaly Ditthiait is a 26-year-old mom of two who works at a bus factory owned by New Flyer Industries in St. Cloud, Minnesota. When Khanthaly was just 18 years old, she got a job as a painter’s assistant at the factory.

“It was 10 years before they hired any women to paint the buses — I was the first girl that they hired,” she says. “It was like, ‘Oh, you can’t do it, you’re short. And you have boobs.’ But I was determined. I was like,

» Read more about: In Praise of Unsung Women and Their Work »

Tuesday is the 103rd anniversary of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire, a major turning point in American labor history. On March 25, 1911, 146 garment workers, most of them Jewish and Italian immigrant girls in their teens and twenties, perished after a fire broke out at the Triangle factory in New York City’s Greenwich Village. Even after the fire, the city’s businesses continued to insist they could regulate themselves, but the deaths clearly demonstrated that companies like Triangle, if left to their own devices, would not concern themselves with their workers’ safety. Despite this business opposition, the public’s response to the fire and to the 146 deaths led to landmark state regulations.

Businesses today, and their allies in Congress and the statehouses, are making the same arguments against government regulation that New York’s business leaders made a century ago. The current hue and cry about “burdensome government regulations”

» Read more about: Remembering the Triangle Fire’s Lessons »

For a long time now, we’ve been a nation of brands. We have our favorite candy bars, sodas, toothpastes and even TV channels. We watch, use and eat “our” brands and leave the others on the shelf. But few of us realize how many of those items we love are actually owned by the same conglomerate – huge financial institutions that consolidate into their systems one product after another.

And often, what we don’t know can hurt our communities. When a handful of companies own all of the most popular brands that Americans use every day, they hold a privileged monopoly on our lives. Capitalism is supposed to offer choice, but more and more the decision is between one huge marketing scheme and another. Capitalism is supposed to foster consumer democracy, but instead it channels our choices into a few mega-corporations that are enriched by our loyalties.

Take media.

It was a busy time for hard-right politicians visiting the Bay Area this week. First, Kentucky Senator Rand Paul stepped into the lion’s den of Berkeley, where he flashed civil liberties cred by denouncing domestic spying before a University of California audience. He was followed by Texas Governor Rick Perry who, with tax breaks and other incentives, tried to coax some Silicon Valley nabobs into burnishing the “tech” in Texas by relocating there. Although these two Republicans are clearly limbering up for presidential runs in 2016, Perry’s visit got comparatively scant media coverage. One reason may be the perception that Paul, who recently won the Conservative Political Action Conference’s straw poll, is the man on horseback right now while Perry is, well, Rick Perry.

It was a busy time for hard-right politicians visiting the Bay Area this week. First, Kentucky Senator Rand Paul stepped into the lion’s den of Berkeley, where he flashed civil liberties cred by denouncing domestic spying before a University of California audience. He was followed by Texas Governor Rick Perry who, with tax breaks and other incentives, tried to coax some Silicon Valley nabobs into burnishing the “tech” in Texas by relocating there. Although these two Republicans are clearly limbering up for presidential runs in 2016, Perry’s visit got comparatively scant media coverage. One reason may be the perception that Paul, who recently won the Conservative Political Action Conference’s straw poll, is the man on horseback right now while Perry is, well, Rick Perry.

Another reason might be that Perry’s brief visit seemed like a follow-up house call from his widely covered 2013 grand tour, during which he attempted to poach jobs from six states (California,

» Read more about: Rick Perry’s Tall Texas Tales of Job Creation »