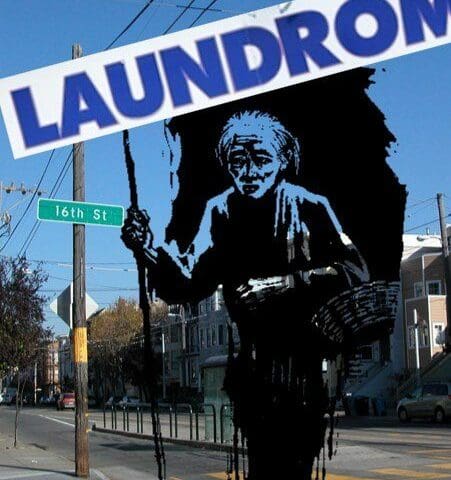

(The New York Times’ Thomas Friedman fancies himself a prophet who can foresee the future. Just look at his recent column on the “Sharing Economy” to see what the future has in store for us. Not good enough? I’ve studied Friedman’s ways and also learned to see the future. In fact, I’ve gotten so good at it that I’ve already written his next column.)

The Washed-Out Economy

Bill Richman and Teddy Wealthman were San Francisco roommates with a problem.

“We worked all the time at our well-paying Silicon Valley jobs,” Bill recently told me, “and didn’t have time to do our laundry.”

So Bill and Teddy got an idea. While walking down 16th Street in San Francisco’s Mission District, on their way to get a $6-dollar cup of single-origin,

So Bill and Teddy got an idea. While walking down 16th Street in San Francisco’s Mission District, on their way to get a $6-dollar cup of single-origin,

» Read more about: Through Thomas Friedman’s Looking Glass »

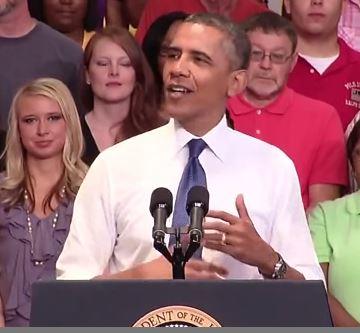

On [July 30], President Obama gave a great speech on why good jobs are the foundation for his middle-out economic strategy… from a huge Amazon warehouse where the workers do not have good jobs. I’m still stuck on the setting.

On [July 30], President Obama gave a great speech on why good jobs are the foundation for his middle-out economic strategy… from a huge Amazon warehouse where the workers do not have good jobs. I’m still stuck on the setting.

There is so much in President Obama’s speech that I’ve been wanting him to say. While the press focused on his announcement of a proposal on corporate taxes, the speech was almost entirely about jobs. After Obama described “what it means to be middle-class in America” as “A good job. A good education. A home to call your own. Affordable health care… A secure retirement,” he pointed out, “It’s hard to get the other stuff if you don’t have a good job.”

He told the Amazon warehouse workers, “we should be doing everything we can as a country to create more good jobs that pay good wages.”

But as The New York Times reported,

In the Appalachian foothills of Georgia, about an hour north of Atlanta, the riverfront city of Rome serves as a regional hub for health care. Near Rome’s tree-lined historic downtown, there are two well-equipped acute care hospitals with a total of more than 530 beds. Two years ago, the Medical College of Georgia opened a satellite campus in the city.

But in Rome, 27 percent of adults under 65 are uninsured, a rate that holds true across the state. Last year, the city’s two hospitals report spending more than $80 million delivering uncompensated care, often in the emergency room, where costs run high. Taxpayers and those with health insurance will end up paying for that care through government subsidies and higher premiums, industry experts say.

Rome’s dilemma is exactly the situation that the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, also known as “Obamacare,” was designed to fix — but that fix isn’t coming to Georgia.

» Read more about: Dixie Governors Say No to Expanding Medicaid »

It’s August, and Americans by the millions are cramming themselves into coach-class seats as they embark on their summer vacations. Those able to learn from adversity might ponder this: Airline seating may be the best concrete expression of what’s happened to the economy in recent decades.

It’s August, and Americans by the millions are cramming themselves into coach-class seats as they embark on their summer vacations. Those able to learn from adversity might ponder this: Airline seating may be the best concrete expression of what’s happened to the economy in recent decades.

Airlines are sparing no expense these days to enlarge, upgrade and increase the price of their first-class and business-class seating. As the space and dollars devoted to the front of the planes increase, something else has to be diminished, and, as multitudes of travelers can attest, it’s the experience of flying coach. The joys of air travel — once common to all who flew — have been redistributed upward and are now reserved for the well-heeled few.

The new business-class seats that Lufthansa is installing convert to quasi-beds that are six-feet six-inches long and two feet wide, the New York Times’ Jad Mouawad reports.

» Read more about: Economic Inequality: The Sky’s Not the Limit »

Over 200 Oakland recycling workers staged a powerful show of unity and action by striking on Tuesday, July 30. Employees from the city’s two recycling contractors – Waste Management and California Waste Solutions (CWS) – walked off their jobs midway through the morning shift.

Over 200 Oakland recycling workers staged a powerful show of unity and action by striking on Tuesday, July 30. Employees from the city’s two recycling contractors – Waste Management and California Waste Solutions (CWS) – walked off their jobs midway through the morning shift.

Then, instead of picketing in remote industrial areas where the recycling plants are located, workers formed caravans that converged downtown at Oakland’s City Hall. The result was a full day of political action and solidarity that included marches, “human billboards” along Broadway and 14th Street, visits with local and state elected officials, and a spirited rally. The day ended where rally participants – including many community allies – filled the upper seats of the City Council chambers and addressed the City Council that evening.

Recycling worker Emanuel San Gabriel is one of CWS workers who left his dusty and noisy workplace behind to join the protest.

» Read more about: Waste Happens — So Do Accidents and Death »

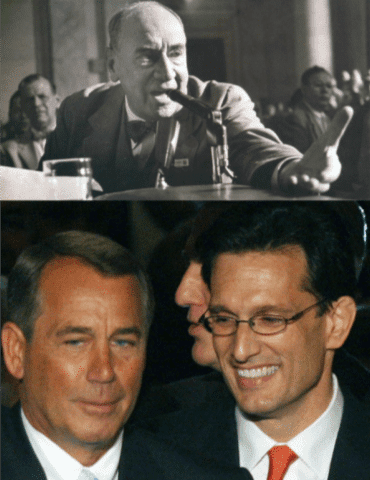

One of the most famous lines not spoken by the man it’s been attributed to is “Have You No Shame?” During the infamous Communist-witch-hunt Hearings of Wisconsin Republican Senator Joseph McCarthy in 1954, attorney Joseph Welch supposedly fired these words at McCarthy. What he actually said, however, is “Have You No Sense of Decency?”

Nevertheless, the first wording, mythical as it is, seems the more appropriate one to ask present-day Republicans, especially in the House of Representatives.

The majority of Americans are not always correct. But their consistently low regard for the present Congress, especially the Republican behavior within it, is dead-on. In a late July 2013 NBC/WSJ poll, only 12 percent approved of the job Congress was doing, while 83 percent disapproved. Another question (and the percentage response indicated afterward) was “Do you think Republicans in Congress are too inflexible in dealing with President Obama (56 percent),

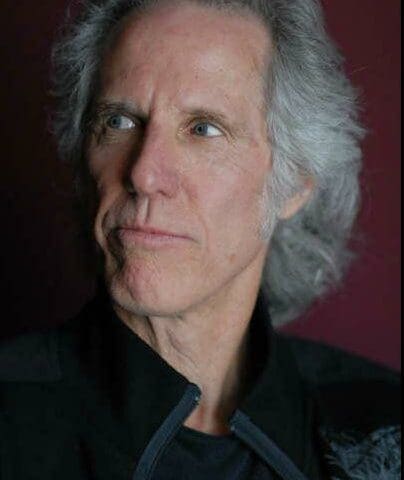

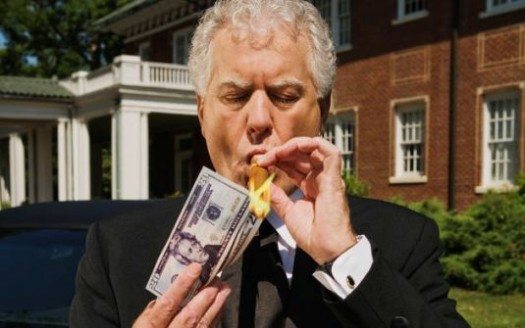

An interview with John Densmore is less a linear dialogue and more a jazz improvisation, with unexpected twists and turns and no clear beginning or end. Which is not to say that the Doors’ drummer is without a steady beat — this is a man determined to drive home his message about the corrosive effects of greed. Densmore’s convictions led him to sue his former bandmates, Ray Manzarek and Robby Krieger, for trying to tour under the name “The Doors of the 21st Century” and using the band’s logo.

Densmore prevailed, but not without a bruising battle that created a bitter divide between the artists who once teamed with Jim Morrison on one of the greatest rock and roll bands in history. The story of that clash is the subject of Densmore’s latest book, The Doors Unhinged: Jim Morrison’s Legacy Goes to Trial.

Frying Pan News caught up with Densmore recently and riffed with him about what he calls “The Greed Gene,” Morrison’s views on money and his reconciliation with Manzarek before the keyboardist’s death earlier this year.

» Read more about: The Doors’ John Densmore Beats the Drum Against Greed »

The Affordable Care Act, or Obamacare as it’s referred to, is going to dramatically change the way we live our lives and balance our budgets. The largest group of beneficiaries is working people who are currently not covered by their employer yet don’t earn enough to buy health insurance on their own, including a large number of food service and retail workers. These workers currently are forced to pay out of pocket, forgo medical treatment or rely on public health clinics.

You’d imagine these workers would be jumping for joy at the thought of a new federal law requiring their employers to help them meet a critical human need. Unfortunately, there is little recourse for these workers for the next two years. While most of the healthcare dialogue has revolved around the individual requirement, the recent announcement that the employer mandate will be pushed back until 2015 has quietly fallen off the radar.

A specter is haunting Detroit — the specter of the Koch Brothers’ toxic brand of unregulated corporatism, as embodied in a cloud bank of pollution that recently blackened the Motor City’s horizon. Abby Zimet, writing in Common Dreams, describes the event as captured by a

[m]ind-boggling video of a billowing, high-carbon, high-sulfur cloud from the mountain of petroleum coke – waste from Canadian tar sands shipped from Alberta to Detroit, and the dirtiest potential energy source ever – illegally stored by the Koch Brothers along the Detroit River. Produced by Marathon Refinery but owned by Koch Carbon, the pet-coke piles have for months been producing “fugitive dust” – i.e.: thick black crud – that blankets the homes of outraged residents and lawmakers; analysis shows the dust contains elevated levels of lead, sulfur, zinc and the likely carcinogenic vanadium.

As we noted here last year,

» Read more about: Koch Brothers’ Huge Coke Cloud Darkens Detroit »

Instead of spending August on the beach, corporate lobbyists are readying arguments for when Congress returns in September about why corporate taxes should be lowered.

Instead of spending August on the beach, corporate lobbyists are readying arguments for when Congress returns in September about why corporate taxes should be lowered.

But they’re lies. You need to know why so you can spread the truth.

Lie #1: U.S. corporate tax rates are higher than the tax rates of other big economies. Wrong. After deductions and tax credits, the average corporate tax rate in the U.S. is lower. According to the Congressional Research Service, the United States has an effective corporate tax rate of 27.1 percent, compared to an average of 27.7 percent in the other large economies of the world.

Lie #2: U.S. corporations need lower taxes in order to make investments in new jobs. Wrong again. Corporations are sitting on almost $2 trillion of cash they don’t know what to do with. The 1,000 largest U.S. corporations alone are hoarding almost $1 trillion.

» Read more about: Corporations to Congress: Cut Our Taxes Now! »