California has roughly a dozen labor codes governing wage-theft on the books, with more proposed each year in the state legislature. Are these laws proving effective? Fausto Hernandez is one worker who doesn’t think they are. The 55-year-old native of Oaxaca, Mexico, has labored in the carwash business for a decade.

“For several years I worked at Slauson Carwash in South L.A. — 10 to 11 hours a day,” he told Capital & Main. “The employer would only pay me for three hours, never for all the hours I worked.”

According to Hernandez, he sought relief by contacting the CLEAN Carwash Campaign, a community coalition led by the United Steelworkers union. The campaign helped him file a claim with the Division of Labor Standards Enforcement (DLSE), an office of the state’s Labor Commissioner.

Workers who take such action face employer retaliation. Hernandez’s employer fired him, he said.

Wage theft is a serious yet seldom-reported crime that victimizes millions of Americans – particularly low-income and immigrant workers. Today, as part of an ongoing examination of workplace issues, Capital & Main debuts a new series focusing on wage theft, beginning with a primer on the problem by Bobbi Murray, followed by Joe Rihn’s profile of a port truck driver who works in an industry where wage theft is a daily fact of life.

The expression “wage theft” is a deceptively gentle term. Perhaps “paycheck mugging” more accurately describes the violence done to the earnings of millions of Americans each year.

If you are a target of wage theft no one pistol-whips you to acquire your valuables–but you definitely get robbed. Every week Los Angeles workers get held up for $26.2 million through unpaid overtime, being pressured to work through unpaid breaks or off the clock;

» Read more about: Wage Theft Confidential: How Your Earnings Are Stolen »

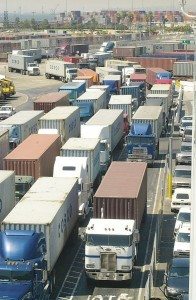

For Victor Vitela life revolves around work. A reserved man with dark hair and a powerful frame, Victor makes his living driving an 18-wheeler loaded with cargo back and forth from the ports of Long Beach and Los Angeles to the Inland Empire. His tone is matter of fact when he talks about his job with QTS Inc., a Gardena-based hauling firm. Victor often works late, until three or four in the morning, leaving just enough time to catch a few hours of sleep before the day begins again at 7 a.m. In his line of work, 20-hour days are the norm. That doesn’t leave enough time to return to his family in Ventura County, so he spends Monday through Friday living out of his truck.

Victor may spend a huge amount of time working for QTS, but you wouldn’t know it from his paycheck, which is eaten up by the kind of expenses and deductions many employers would be expected to pay – the insurance on his truck,

» Read more about: Wage Theft Confidential: A Truck Driver’s Story »

Readers of Capital & Main are all too familiar with wage theft and job misclassification – twin plagues that afflict American workers, especially truck drivers at the Los Angeles and Long Beach ports. Employers use wage theft to shortchange employees out of their wages and benefits by shaving hours off time cards; job misclassification, on the other hand, allows companies to deny that the people working for them are even employees at all, but freelancers who are ineligible for government-provided benefits such as unemployment insurance and workers’ compensation. By misclassifying their workers, employers do not pay the kinds of payroll taxes that provide these and other services to workers.

Now, thanks to an epic investigative series published yesterday by the McClatchy news syndicate (publisher of the Sacramento Bee), in partnership with ProPublica, these two issues have been pushed before a national audience.

» Read more about: News Series Exposes Massive Employer Fraud in Construction »

California wage earners received encouraging news Wednesday when Assembly Bill 2416 (Wage Theft Recovery Act) cleared a major hurdle by passing 44 to 27 on an Assembly floor vote — three votes more than needed to move to the Senate.

The measure, introduced in February by Mark Stone (D-Scotts Valley), is modeled after a successful Wisconsin wage lien law. It is designed to tie off loopholes in California that currently allow unscrupulous businesses to evade paying monetary judgments to thousands of shortchanged, mostly low-wage workers by simply transferring ownership or even by declaring bankruptcy.

According to a 2013 study by the National Employment Law Project and the UCLA Labor Center, of the 18,683 workers who filed claims for unpaid wages with the California Division of Labor Standards Enforcement (DLSE) between 2008 to 2011, only 3,084, or 17 percent, recovered any money at all.

In 60 percent of those rulings,

» Read more about: Proposed Wage Theft Law Passes Major Hurdle »

The gaudy evidence of income inequality is all around us: stratospheric CEO “wages,” private plane shuttles to Coachella, gated enclaves and all the rest. But few things say “class war” more eloquently than wage theft, the practice by unscrupulous businesses of short-changing their employees by undercounting work hours or shaving off time for breaks that were never taken.

Wage theft is probably about a minute older than ancient history’s first labor handshake and partly exists because most workers who suffer it are too financially insecure to complain. Now, however, there is increasing pushback from some city and state governments, and from workers themselves –McDonald’s low-wage employees have filed class action lawsuits in several states to recover wages they allege were gouged from their paychecks.

In California, Assembly Bill 2416 (“California Wage Theft Prevention Act”), introduced by Mark Stone (D-Monterey Bay), seeks to curb wage theft by allowing workers to file liens against the real and business property of employers they claim owe them wages.

» Read more about: Lien In: New California Bill Seeks to Curb Wage Theft »

Last week, we reported on the legal struggle at port trucking company Seacon Logix, whose drivers filed claims with the California Division of Labor Standards Enforcement (DLSE) seeking reimbursement for a number of wage-and- hour violations, including illegal paycheck deductions made by the company. After the DLSE ruled in favor of the drivers in early 2012 – finding that the drivers were not independent contractors, but were actually misclassified employees – the company appealed the ruling.

On Thursday, a California Superior Court judge ruled in favor of the drivers in every respect, coming to the same conclusions as the DLSE. The court found that drivers were misclassified and ordered the company to pay the four drivers $107,802. Five additional drivers at the same company have similar claims pending.

This is the first in an anticipated wave of rulings addressing conditions for misclassified port truck drivers.

» Read more about: Court: Seacon Logix Port Truck Drivers Are Misclassified »

Every year millions of Americans are victims of what some call wage theft — a practice in which a company fails to compensate workers for their time, short-changes them on their benefits or intentionally misclassifies employees in order to save money. And even though all that is illegal, Kim Bobo, executive director of Interfaith Worker Justice and author of Wage Theft in America, says it’s surprisingly common in the U.S.

“Minimum wage and overtime violations are two of the most common ways that wage theft occurs. Another way is payroll fraud, when employers intentionally call people independent contractors when they are really employees. Now if your boss — not you — declares you an independent contractor, you probably aren’t one. Then there is also tip stealing. About 10 percent of tipped workers actually don’t get their tips; their employers just don’t give it to them,” says Bobo.