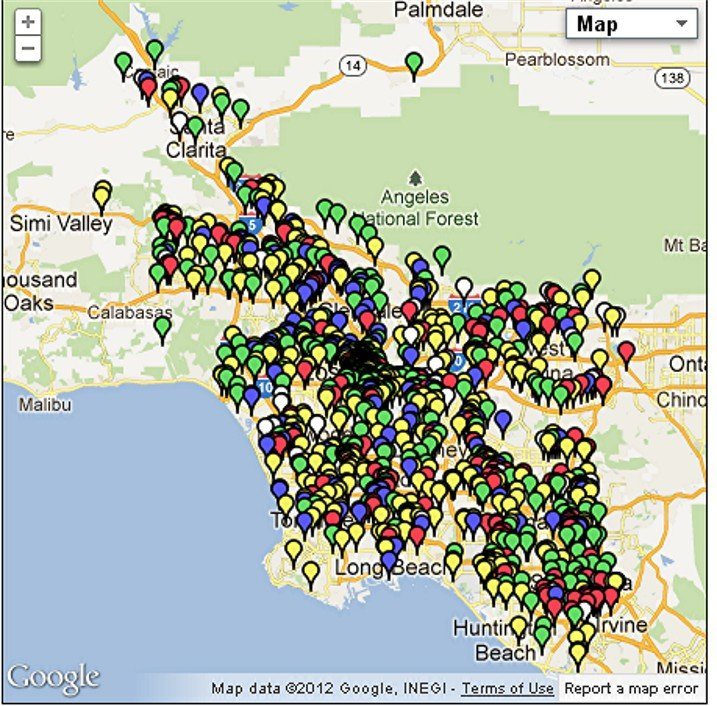

Here’s a Google map you may not want to be consulting any time soon – at least without a drink in hand. It’s the one used by Working America‘s Job Tracker feature that shows the locations of American jobs reported to be leaving your community. By punching in a ZIP Code, you’ll be able to see which companies are exporting jobs or laying off employees, as well as those which have been cited for health and safety violations.

Entering one L.A. ZIP brought up the scary-looking map above, along with links spelling out who’s involved and where this labor triage is taking place within a 50-mile radius of the ZIP Code.

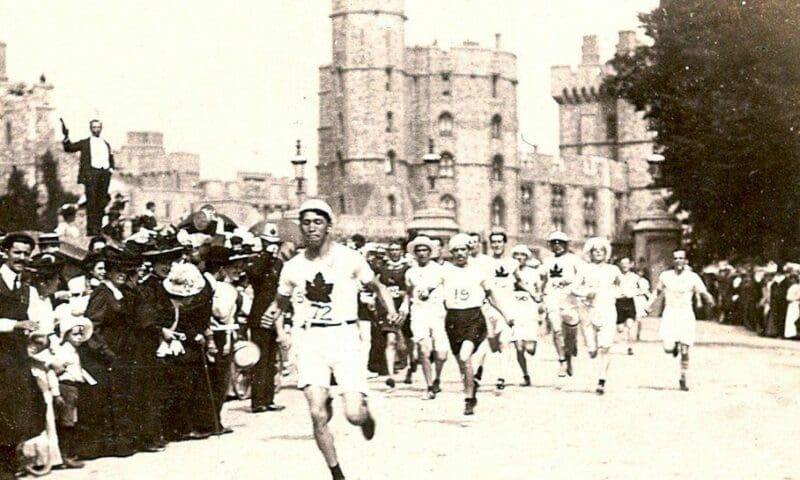

Leader of the Pack: Tom Longboat (72) and Dorando Pietri (19) leaving Windsor Castle

When Olympic marathon races first appeared in the 1896 Athens games, the route was a somewhat arbitrarily chosen 25 miles and, contrary to popular myth, had no authentic origin in Greek history. By the time of the 1908 London Olympiad, the length had been even more whimsically extended to 26 miles, 385 yards – the exact distance between its starting point at Windsor Castle and the course’s terminus at a massive, barely completed stadium in Shepherd’s Bush. Among other things, trainers in those days believed it was bad for their runners to drink water while running and instead kept them supplied with shots of brandy, whisky and – in a pinch – strychnine, which was used as a stimulant.

These are just some of the many revelations to be found in David Davis’ Showdown at Shepherd’s Bush: The 1908 Olympic Marathon and the Three Runners Who Launched a Sporting Craze,

» Read more about: Marathon Men: Class, Race and Races at the 1908 Olympics »

Los Angeles was granted its anticipated funding for America Fast Forward, a project aiming to expedite construction of more extensive and functional public transportation systems. The project’s approval is a victory for both the people of Los Angeles and Mayor Villaraigosa, who has been supporting it for years.

America Fast Forward is a provision of a larger transportation bill approved by Congress in late June and signed into law by President Obama last week. The $100 billion package, which received rare bipartisan support, will reduce harmful emissions, fund the construction of mass transit projects in multiple cities and create thousands of jobs throughout the country.

That’s the good news. On the downside, the law — which hardly resembles earlier versions of the legislation — cuts funding for a number of important programs and puts off critical decisions by only providing monies through 2014.

L.A.’s program would initially be funded by the Transportation Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act (TIFIA),

» Read more about: A Good News-Bad News Transportation Law »

The Fourth of July parade rolled down Main Street in Santa Monica while I sat at the computer writing this. Only half a block away, I could hear the sirens and the bands and the sound trucks. What kept me here instead of there was a desire to reflect, not celebrate. Twice a year – on Martin Luther King’s birthday in January and now – I think about the state of American democracy.

The Fourth of July parade rolled down Main Street in Santa Monica while I sat at the computer writing this. Only half a block away, I could hear the sirens and the bands and the sound trucks. What kept me here instead of there was a desire to reflect, not celebrate. Twice a year – on Martin Luther King’s birthday in January and now – I think about the state of American democracy.

I believe in democracy. I believe that democracy is the best form of government human beings have devised to date because it allows people to actually make changes in the government when they feel it’s required. Monarchies, aristocracies, dictatorships and oligarchies preclude that option. In Western civilization, this country broke the tradition of absolute power to create a republic – although participation was narrow: Voting was limited to male property owners. Over the next 150 years those rights expanded.

» Read more about: A Parade Passed By: Rethinking Our Democracy »

After growing up in L.A., I got used to hearing my hometown disparaged as superficial, anti-intellectual, not a “real” city, celebrity obsessed, etc. etc. It was shocking to me that Los Angeles could be so easily dismissed by people who hadn’t even visited here and seen how great a place it really is. Even deep thinkers from Northern California looked (and still look) down on our town from the ivory towers of San Francisco and Berkeley, as if Southern California doesn’t represent the majority of the people in our state and most of its social and political energy.

And we Angelenos, rather than defend our town, have often accepted the judgment of others – that L.A. isn’t a serious place, doesn’t produce important scholarship, and is well behind the intelligence curve.

Well, if you need a boost to your hometown ego, spend some time at the Hammer Museum’s new show Made in L.A.,

Much has been said in recent months about the labor movement’s “impending decline,” with the right wing’s unrelenting attacks against collective bargaining rights in states across the country, from Arizona to Wisconsin to New Jersey. California is facing its own version of this attack with the qualification of the Paycheck Deception initiative for the November 2012 ballot that would dramatically curtail working people’s ability to participate in politics in the state.

Many people in the modern progressive movement date the beginning of these assaults to Ronald Reagan’s 1981 decision to fire 12,000 air traffic controllers after their union, PATCO, went on strike and shut down the nation’s airports. President Reagan’s decision to permanently fire (and prohibit any rehire of) all the controllers destroyed PATCO and served as the starting-pistol shot for three decades of attacks on the right to collective bargaining, that continue today.

» Read more about: How PATCO Crashed – But Why Unions Don’t Have To »

Last week in Stockton, the United Farm Workers signed a three-year contract with Pacific Triple E Ltd., a large tomato grower-shipper based in Tracy, California. According to The Record, the agreement represents the first time the UFW has enjoyed a membership presence in San Joaquin County in more than two decades.

The Packer, an industry newsletter, described Triple E as “a family owned company” operating in Fresno, Merced, Madera, San Joaquin and Sacramento counties. The union’s Web site announcing the pact included the following message from UFW president Arturo Rodriguez:

Thank you for being there for the United Farm Workers. Your support means so much to me and the workers we are here to serve. I want to share some wonderful breaking news with you.

Yesterday, we used a contract signing ceremony in Stockton to congratulate the 800 workers at Pacific Triple E Ltd.

» Read more about: UFW Wins New Tomato Contract in Central Valley »

(The following post appeared on the blog of the International Association of Machinists — IAM.)

If the Trans Pacific Partnership agreement (TPP) is signed into law at the end of this year, the rules for international trade and the global economy will change dramatically, and not for the better.

Despite the potential for the TPP to negatively impact hundreds of thousands of American jobs, the negotiations to create the massive trade pact are being conducted in unprecedented secrecy. Access to the pact’s draft language is limited almost exclusively to a handful of government negotiators and corporate advisers.

Among those denied access to the pending terms of the trade deal was Senator Ron Wyden (D-OR), chairman of the U.S. Senate Finance Subcommittee on International Trade, Customs and Global Competitiveness. Outraged, Wyden responded with a bill demanding greater transparency in the negotiations. Over 130 members of Congress also took action,

» Read more about: Trans Pacific Partnership: Exporting US Jobs »

On July 3 the Asian Pacific American Labor Alliance (APALA) and United Food and Commercial Workers Local 770 filed a lawsuit challenging the City of Los Angeles’ handling of Walmart’s controversial Chinatown store project.

On July 3 the Asian Pacific American Labor Alliance (APALA) and United Food and Commercial Workers Local 770 filed a lawsuit challenging the City of Los Angeles’ handling of Walmart’s controversial Chinatown store project.

The suit alleges that the L.A. City Department of Building and Safety failed to notify the public of its decision to issue a Notice of Exemption (NOE), which allows Walmart to move forward on its Chinatown project without environmental review. The lawsuit also asks a judge to stop construction at the store.

The plaintiffs in the lawsuit are asking a judge to find the exemption invalid and require that a new one be issued. Because the building permits are being appealed – an initial hearing is expected in August – the lawsuit argues that the exemption should not have been issued until the appeal process was exhausted.

The notice to the public of the exemption is intended to prevent the appearance of backroom deals.

» Read more about: Lawsuit Challenges City’s Actions on Walmart Chinatown Store »

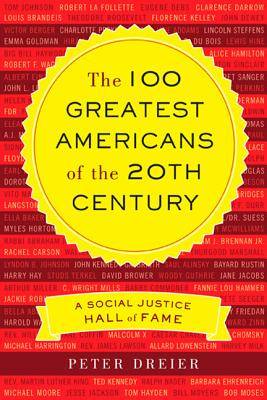

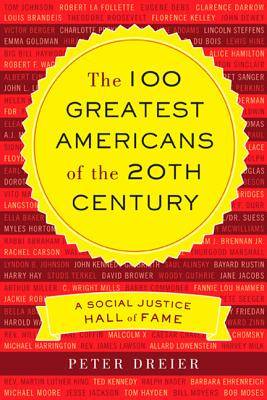

Writer/professor Peter Dreier’s new book is called The 100 Greatest Americans of the 20th Century, a nervy title that dares readers to take a poke at the author’s chin. A corrective to Greatest Generation blather, Dreier’s 100 profiles refract a century of progressive movements through the lives of leaders whose native radicalism helped push America toward a more humane vision of society.

Dreier’s inclusions and omissions will thrill some and bewilder others: Roger Baldwin’s here but not James Baldwin; there’s Mother Jones but no LeRoi Jones. Playwright Tony Kushner ends the list on an intellectual note, yet there’s no mention of a Philip Rahv or any Partisan Reviewers, Algonquin Tablemates, Beats or Bohemians.

Of course, provoking debate about who should be included in a “Social Justice Hall of Fame” (the book’s subtitle) is a clever way to stir discussion about history and activism.

» Read more about: Peter Dreier’s A-List of 20th Century Greats »