Politics & Government

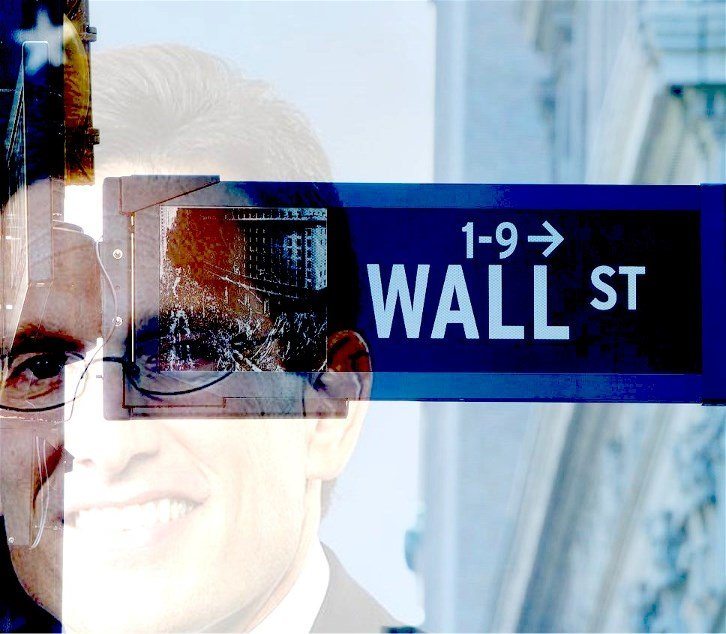

The Big Money: Eric Cantor Goes to Wall Street

When House Majority Leader Eric Cantor lost his primary bid for re-election, he wasted no time cashing in on new opportunities. He didn’t even wait for his term to end before resigning his office August 18 – leaving his constituents unrepresented for three months, and making the leap to big bucks on Wall Street. His base pay in his new position with the investment firm Moelis & Co. is $400,000 for the remainder of the year, plus a $400,000 signing bonus. He also gets a million dollars-worth of restricted stock – altogether about 26 times the average income of Virginians in his old district.

What makes an ex-Congressman so valuable to an investment firm based in New York City? To be clear, he cannot return to the floor of the House to lobby his former colleagues on a bill. Congress ended that practice in the middle of the last decade. Nor does he have life-long access to Congressional workout rooms, restaurants or recreation areas, unless he rejects registering as a lobbyist. Congress ended that one too. He’s even barred from lobbying Administration officials on any issue for two years.

What makes Cantor so valuable is this: He knows people, he knows how the place works and he knows where to put the money to get what he wants. After all, that is what he did as Majority Leader. The people in power positions in Congress – party leaders or committee chairs – raise money from major sectors of the economy and steer it toward districts where the cash will secure seats for their party. Democrats do it just like Republicans. They know the rules and how the process works to either stop or modify legislation. Even if they don’t register as lobbyists, former electeds can plan the strategy for a lobbying effort’s success. A former representative knows the current Congress people or staff members who have the power to get things done in the interest of an industry.

While an ex-member of Congress doesn’t need to be an official lobbyist to do those things, about a quarter of all Democratic and half of all Republican ex-members eventually become lobbyists. Democrat Dick Gephardt is a good example, a former House Majority Leader who created his own firm after a failed gamble for his party’s presidential nomination. The man who once led the efforts for universal health care and tirelessly supported labor unions now represents the likes of coal companies, financial institutions and a Who’s Who of multinational corporations. So, moving from a legislative office or a regulatory agency to the private sector and back again as a lobbyist has become common practice – it’s the revolving door of politics.

Some corporations even offer what might be called a resignation bonus if the person leaving the firm is headed to Washington to run a regulatory commission. Jack Lew received a small bundle when he left Citigroup to become Secretary of the Treasury – where he would make financial policy decisions seriously affecting banks and brokerages. I suppose this was meant to tide him over during the lean years on a government salary.

On the other end, offering a Congressional committee staffer or a federal commission employee a future with the industry they currently help regulate virtually buys them, or at least that is what one disgraced ex-lobbyist said. How many underpaid but key people in the decision-making process will want to implement policies that might antagonize their future employers? It’s a calculated choice made all the time in Washington.

So for groups that transact business regulated by federal laws or commissions, paying for a friendly voice hedges against expensive decisions that might cost their industries serious money. It’s why corporations and industrial sectors dealing in pesticides, biotechnology, homeland security, media, military contracts, auto safety and fossil fuels, among others, all contract with lobbyists and hire former Congress or commission members or their staff.

When Toyota had a problem with sudden-acceleration, getting to the right people in government for a sit-down saved the company an estimated $100 million. Or when Dow Chemical faced a phase-out of one of its big-selling but lethal agricultural products, getting the regulators on the same page kept the poison flowing onto our fruits and vegetables, while sickening field workers. The lobbying money and the big salaries paid for themselves tens of times over.

No wonder Eric Cantor took the big paycheck and left office early. He was just moving from one position to another in the same arena. He went from carrying water for the big financial institutions in Congress to carrying that same water to Congress. Only now he can make a lot more money for the service.

-

State of InequalityApril 4, 2024

State of InequalityApril 4, 2024No, the New Minimum Wage Won’t Wreck the Fast Food Industry or the Economy

-

State of InequalityApril 18, 2024

State of InequalityApril 18, 2024Critical Audit of California’s Efforts to Reduce Homelessness Has Silver Linings

-

State of InequalityMarch 21, 2024

State of InequalityMarch 21, 2024Nurses Union Says State Watchdog Does Not Adequately Investigate Staffing Crisis

-

Latest NewsApril 5, 2024

Latest NewsApril 5, 2024Economist Michael Reich on Why California Fast-Food Wages Can Rise Without Job Losses and Higher Prices

-

California UncoveredApril 19, 2024

California UncoveredApril 19, 2024Los Angeles’ Black Churches Join National Effort to Support Dementia Patients and Their Families

-

Latest NewsMarch 22, 2024

Latest NewsMarch 22, 2024In Georgia, a Basic Income Program’s Success With Black Women Adds to Growing National Interest

-

Latest NewsApril 8, 2024

Latest NewsApril 8, 2024Report: Banks Should Set Stricter Climate Goals for Agriculture Clients

-

Striking BackMarch 25, 2024

Striking BackMarch 25, 2024Unionizing Planned Parenthood