The Slick

New Mexico Leaders Promote Hydrogen Production Despite Questionable Environmental Benefits

Hydrogen production would dramatically increase natural gas development in a state that already struggles to police natural gas operators.

Two big hydrogen-based business projects are the cusp of a wave of investment and jobs that New Mexico Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham hopes to see wash across the state — and they have arrived before her Hydrogen Hub Act had a chance to debut at the upcoming legislative session. That act is to be her signature bill for next year, and a draft version highlighted wide-ranging tax breaks for hydrogen production and use in everything from transportation to power generation.

All indications are that the state’s abundant natural gas deposits will fuel this hydrogen future, creating so-called blue hydrogen, as opposed to green hydrogen, which is derived from renewable energy sources and water. And blue hydrogen has much of the state’s environmental community up in arms.

That’s because making it “green” for the environment requires plugging leaks in the natural gas production chain and permanently sequestering the carbon emitted during the hydrogen-making process.

And a pair of recent scientific studies claim that leaks in the natural gas production chain — even if dramatically reduced — would negate any potential benefit of hydrogen made from natural gas.

New Mexico already has trouble policing natural gas operators, and hydrogen production would dramatically increase natural gas development in a state already breaking records for fossil fuel production. And one of the two hydrogen projects would require what may become one of the world’s largest carbon-sequestration programs.

New Mexico Environment Department (NMED) Cabinet Secretary James Kenney, who has enthusiastically supported the governor’s plans, readily admits the state’s problem with emissions from existing natural gas wells and infrastructure.

“One hundred percent, we are not where we need to be to hold the industry accountable,” he says.

“I have more violations than I have staff to work on them,” he continues. “That’s a huge struggle and point of frustration.”

Without dramatic funding increases for both his department and the state’s Oil Conservation Division (OCD), hydrogen production and its associated natural gas production could ramp up ahead of the state’s ability to stop fugitive gas field emissions.

That would quickly negate any environmental benefits of hydrogen fuel produced here and completely derail the governor’s statewide decarbonization goals. That’s because natural gas is composed of up to 90% methane, a greenhouse gas that is up to 80 times more potent in its heat-trapping properties than CO2.

And a pair of recent scientific studies claim that leaks in the natural gas production chain — even if dramatically reduced — would negate any potential benefit of hydrogen made from natural gas.

Making hydrogen has serious environmental pitfalls, especially when the gas is made via steam methane reforming, a process that compresses and heats natural gas to break off hydrogen.

Compared to traditional fossil fuels, hydrogen does offer impressive benefits, depending on how it’s consumed: It produces nothing but heat and water as waste when run through a fuel cell to make electricity; when blended and burned with natural gas it reduces — but doesn’t eliminate — the amount of resulting CO2 from burning natural gas alone. And when burned alone it creates nitrous oxides — potent air pollutants — but no CO2.

Yet making hydrogen has serious environmental pitfalls, especially when the gas is made via steam methane reforming (SMR), a process that compresses and heats natural gas to break off hydrogen. It is a highly energy-intensive process, and it creates a lot of CO2 as a byproduct.

That SMR process is at the center of two projects currently rolling out in New Mexico.

* * *

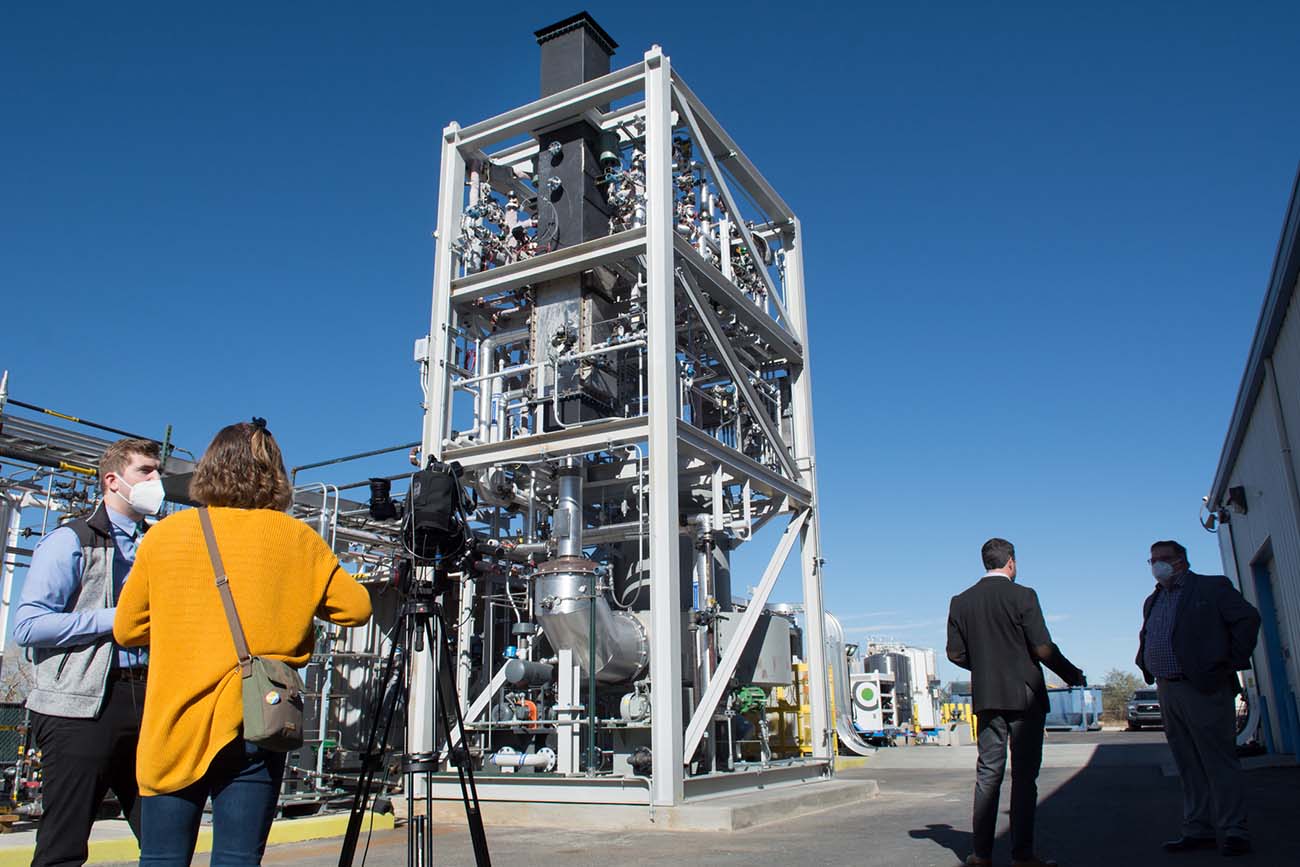

In early December, Lujan Grisham toured Albuquerque-based BayoTech, marking that company’s partnership with the New Mexico Gas Company (NMGC). The gas company is the first customer for BayoTech’s new compact hydrogen-making machine — a shiny, two-story scaffold of pipes and tanks, the size of three shipping containers tipped on end.

“The best way we address the climate crisis is by decarbonizing all of the different sections and sectors,” she said during a talk on the factory floor.

“We are decarbonizing the utility sectors,” she said, and “here’s an opportunity with BayoTech investments and efforts to decarbonize the transportation sector.”

Sort of.

Like the state itself as envisioned in the governor’s plan, this machine, too, is called a hydrogen hub. NMGC is buying one to test blending hydrogen into its gas supplies, and hub production is set to ramp up quickly from there.

“We have plans to deploy three [hydrogen hubs] next year, growing to 14 the year after, and then 50 in the 2024 timeframe,” says Catharine Reid, chief marketing officer at BayoTech.

The hydrogen production system at the BayoTech facility in New Mexico. Photo: Jerry Redfern.

BayoTech’s hub uses an SMR process developed across town at Sandia National Laboratories that makes hydrogen much more efficiently than previous industrial processes. But it still uses a lot of natural gas to do so, and creates CO2 as a byproduct.

How much CO2?

While the hub in BayoTech’s lot produces only one-fifth the hydrogen of their commercial units, a company executive said that a fully operational, final production hub could fuel 200 hydrogen-powered vehicles. Those vehicles would be very green, but according to figures from the company’s website and the EPA’s carbon calculator, over the course of a year, the hub itself would emit as much CO2 as 720 gas-powered cars.

And though they are working with two other companies on possibilities, BayoTech does not make carbon capture technology for their hubs. Unless a customer adds a carbon capture device, it’s just vented to the sky.

And there’s no free lunch in physics and chemistry: It takes more energy to make hydrogen than you get in the hydrogen that results from the process.

* * *

About a hundred miles due west of the BayoTech office in Albuquerque, the mothballed Escalante coal-fired power plant sits in the tiny town of Prewitt, New Mexico. Two days before the event at BayoTech, Kenney and New Mexico Economic Development Department Secretary Alicia Keyes toured the facility that a Texas-based businessman wants to reopen and retrofit to run completely on hydrogen.

Escalante’s previous owner, Tri-State Generation, closed the plant in 2020 to reduce the company’s overall carbon footprint and replace the generated electricity with solar generation.

But to hear Wiley Rhodes tell it, the empty facility is the next best thing to a gold mine.

A few years back, Rhodes, the CEO of Texas-based Newpoint Gas and co-founder of Escalante H2 Power, looked over the horizon and saw the possibility of producing electricity from hydrogen. And then a business associate pointed out the empty Escalante plant.

“The scale of the opportunity and the quality of the opportunity is so big,” he says. “It’s in perfect condition.” Plus, he says, unlike BayoTech, “We were able to take existing technologies and just put them together in a unique sequence to do the project.” Even so, existing technology isn’t cheap. He says the project will cost $600 million and is being funded by Tallgrass Energy, a division of the Blackstone Group investment fund.

His excitement for the project is almost palpable, but it is constrained by one massive physical limitation.

“The scale at which we can develop is going to be determined by how much carbon we can store away.”

He’s talking about a lot of carbon to store, coming from a lot of natural gas.

“Carbon emission reduction and job creation, those have to be the first two topics that you discuss and they have to take priority.”

~ Wiley Rhodes, co-founder of Escalante H2 Power

By Rhodes’ calculations, the plant will use about 78 million cubic feet of natural gas, producing 75 million cubic feet of CO2, and create enough hydrogen to burn for 270 megawatts of energy production — every day. All of the natural gas would be used on-site as the feedstock to make hydrogen.

Rhodes says the hydrogen-powered power plant will be the biggest on the planet.

Current technology doesn’t allow hydrogen to be efficiently burned in a turbine like natural gas, though small amounts can be combined with natural gas to reduce overall emissions, a scenario that carries tax breaks in the governor’s proposed Hydrogen Hub Act.

At Escalante, Rhodes plans to burn the hydrogen directly, boiling water to spin a turbine to make electricity. While burning hydrogen creates no CO2, it does create nitrous oxide (NOx), a potent air pollutant. According to an article from the Union of Concerned Scientists, it can create more than you get from burning natural gas.

Directly downwind from Escalante are the pueblos of Acoma and Laguna, Navajo lands and, eventually, Albuquerque.

“The NOx emissions, it’s a big one. And it’s an important one. And it’s one that is being addressed,” Rhodes says. But, he continues, “Carbon emission reduction and job creation, those have to be the first two topics that you discuss and they have to take priority.”

And then there is the carbon sequestration question.

Massive carbon sequestration projects have a rocky history in North America. And earlier this year, the world’s largest carbon capture and sequestration project closed. Chevron’s massive Gorgon facility on the west coast of Australia simply couldn’t pump enough CO2 into the ground to keep up with production. If Rhodes’ plans hold true, the Escalante project will sequester 1.4 million metric tons of CO2 annually. If it were operational now, it would be among the top-10 sequestration projects on the planet.

* * *

When speaking at BayoTech before the crowd of businesspeople, journalists and TV reporters, Lujan Grisham celebrated the day: “We’re together, literally joined productively at the hip for making meaningful change.”

The early December New Mexico sky was perfectly clear, and the temperatures continued their streak of 15-plus degrees above average, another likely example of a changing climate, fueled by ever-increasing amounts of CO2 in the atmosphere.

That changing climate was the focus for so much of the governor’s efforts during her first three years in office. She pledged to decarbonize the state by 2050, and charged state agencies like OCD and NMED to shut down spills, leaks and waste in the oil and gas sector, which produces more than half of all carbon emissions in the state.

“We’re not going to meet our 2030 goal of a 45% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions unless we do more. And more includes things like hydrogen.”

~ James Kenney, cabinet secretary, New Mexico Environment Department

To that end, the state’s recently implemented methane rules, and soon-to-be implemented ozone precursor rules are, as the governor likes to point out, some of the most progressive in the country.

But those policies still aren’t enough.

“We’re not going to meet our [state] 2030 goal of a 45% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions unless we do more,” Kenney says. “And more includes things like hydrogen.”

Kenney and Lujan Grisham both attended COP26 in Scotland last month. He says there was “a consensus that if you don’t use hydrogen … the ability to get to net zero by 2050, or even meet climate goals by 2030, are in jeopardy.”

While he couldn’t talk in detail, Kenney says that state agencies are talking with companies that are considering making hydrogen from sources other than natural gas, like wastewater treatment or landfill gas. And agencies are considering how to enter the carbon sequestration regulation sphere alongside the federal government.

But success for all of that state work depends on funding.

“You can promulgate all the legislation and rules you want,” he says. “If nobody is complying with them, you don’t gain the benefit environmentally or for public health.” Compliance takes enforcement, and enforcement takes money.

For the upcoming legislative session — which deals almost exclusively with state funding issues — OCD has asked for a 27% increase in funding that would cover 25 new positions to monitor permitting, inspections and compliance. Kenney has asked for a 44% increase at the Environment Department, in part to better monitor emissions from the oil and gas sector. While he hopes that the money will come through, “I can’t be confident.” he says. In the end, “you know, that’s up to the Legislature.”

Copyright 2021 Capital & Main

-

Column - California UncoveredFebruary 6, 2026

Column - California UncoveredFebruary 6, 2026What It’s Like On the Front Line as Health Care Cuts Start to Hit

-

The SlickFebruary 10, 2026

The SlickFebruary 10, 2026New Mexico Again Debates Greenhouse Gas Reductions as Snow Melts

-

Latest NewsFebruary 12, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 12, 2026Trump Administration ‘Wanted to Use Us as a Trophy,’ Says School Board Member Arrested Over Church Protest

-

Latest NewsFebruary 10, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 10, 2026Louisiana Bets Big on ‘Blue Ammonia.’ Communities Along Cancer Alley Brace for the Cost.

-

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 12, 2026

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 12, 2026They’re Organizing to Stop the Next Assault on Immigrant Families

-

The SlickFebruary 16, 2026

The SlickFebruary 16, 2026Pennsylvania Spent Big on a ‘Petrochemical Renaissance.’ It Never Arrived.

-

The SlickFebruary 17, 2026

The SlickFebruary 17, 2026More Lost ‘Horizons’: How New Mexico’s Climate Plan Flamed Out Again

-

Latest NewsFebruary 18, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 18, 2026Effort to Fast-Track Semiconductor Manufacturing Faces Community Pushback