Coronavirus

Missteps in L.A.’s Pandemic Response Left Disadvantaged Communities Behind

New collaborations with community organizations may produce innovative solutions that could make the pandemic recovery more equitable.

As Los Angeles’ COVID-19 winter surge hit its deadly peak last December, the county government launched a new initiative meant to tap trusted community leaders to slow the virus’s spread through information campaigns and distribution of vaccines in hard-hit neighborhoods.

Community organizers told Capital & Main that they’re grateful for the support. But many say the slow rollout of the government-community partnership, which started after the recent surge was waning, is illustrative of both the missteps that have led to lives lost and the change of course needed ahead.

Also Read:

“How Were Los Angeles Hospitals Brought to the Brink by COVID?”

Mixed messages, inaccessible systems, bureaucratic delays, rushed reopenings and weak workplace and housing protections are among the biggest pitfalls, according to interviews with a dozen experts, ranging from public health researchers to policy advocates, community leaders and budget analysts.

“The county needs to listen to the communities and what’s happening on the ground,” said Maria Brenes, who directs InnerCity Struggle, a group on Los Angeles’ Eastside that will collaborate with the county in its new partnership, the Community Equity Fund.

“We can’t have business as usual when people are disproportionately dying.”

~ Maria Brenes, executive director of InnerCity Struggle

The local program, which organizers hope could become a model for statewide and nationwide implementation, is getting started following California Gov. Gavin Newsom’s recent lifting of statewide restrictions and L.A. County’s decision to reopen, even as more highly contagious variants of the coronavirus are spreading and vaccine supplies remain low.

“The definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting a different result,” Brenes said. “We can’t have business as usual when people are disproportionately dying.”

Brenes and other community organizers in South and East Los Angeles — areas bearing the brunt of the pandemic and ensuing economic recession — said that Los Angeles County and some L.A. City Council districts have shown a commitment to increasing equity in the response and recovery.

But the pace has been slow, and other obstacles and leadership blunders have in the meantime intensified the pandemic’s disparate impacts on low income communities of color, experts said. During the surge, from November through January, there were more than 780,000 new cases and 10,000 deaths in Los Angeles County. Since the start of the pandemic, almost 19,000 people have died from COVID-19 in the county. Latinx Angelenos account for more than half of those deaths, but have been underrepresented among those inoculated in early vaccination efforts.

Moving forward, new government collaborations with community organizations, like the Equity Fund, may open the door to innovative solutions that could save lives and make the pandemic recovery more equitable, experts and groups involved said.

* * *

Missteps

Los Angeles, California’s most populous county and city, took an early lead in the nation last year with public health measures and recognition of the pandemic’s disparate outcomes based on race and income. Even with limited federal leadership or assistance, the local government took some steps to respond to the crises’ expected effects on susceptible Angelenos.

A Los Angeles County spokesperson told Capital & Main in an emailed statement that under the leadership of its Board of Supervisors, it “has moved swiftly and urgently to meet the needs of our most vulnerable residents and hardest-hit communities.”

But low income Angelenos of color, who disproportionately work in essential jobs and live in overcrowded, multigenerational housing, have remained at higher risk of contracting the coronavirus and dying.

Los Angeles County has sought to build an “equity lens” into its pandemic response, including in its metrics for reopening and its COVID-19 relief grant-making.

“We’re being hindered by the ghosts of our racist past in terms of being able to effectively address this crisis,” said John Kim, the executive director of the advocacy and data analysis group Advancement Project California.

Biases built into health, housing, employment and other federal, state and local policies over the years have created a government-community trust gap, Kim said. And systems for distributing government assistance aren’t set up to direct resources to those who need them the most.

Nevertheless, Los Angeles County has sought to build an “equity lens” into its pandemic response, including in its metrics for reopening and its COVID-19 relief grant-making. And it has rolled out programs to provide food, housing and other basic necessities to some Angelenos. A county statement emailed to Capital & Main said that the Board of Supervisors and the departments under its purview have been “laser-focused on meeting our safety net responsibilities vigorously, compassionately and with a keen understanding of inequities that this virus has inflicted, especially on Latinx and Black residents and on those who are low-income.”

But a series of missteps have worked counter to that goal, experts told Capital & Main.

Public safety messaging released by Gov. Newsom and local health districts, including the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health, has been inconsistent throughout the pandemic, causing confusion and fueling distrust, said Steven Wallace, a professor at the University of California, Los Angeles, Fielding School of Public Health.

“Pronouncements are made and then they’re changed. Oftentimes for good scientific reasons. But the reasons aren’t really well explained,” Wallace said. And the information is rarely released in the wide range of languages spoken by Californians or tailored to be culturally relevant for the Latinx, Black and other communities of color that have been most affected, Wallace added.

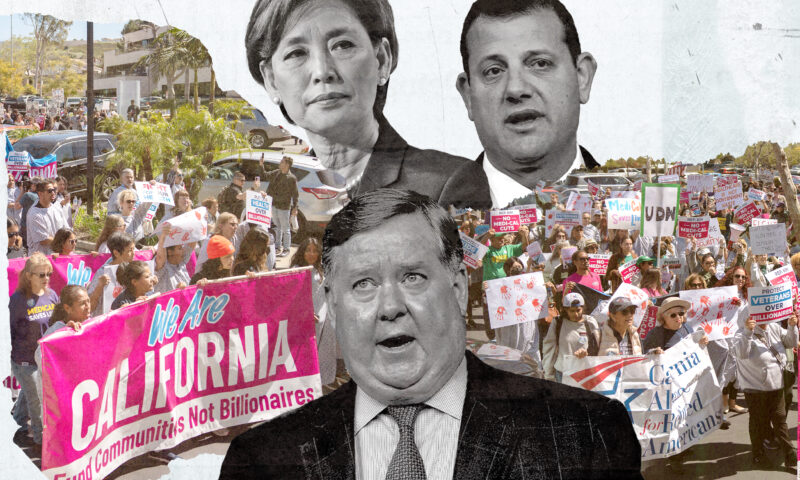

Divided politics have also contributed to the mixed messages. In early December, as hospitals filled to intensive care capacity and death counts grew, the L.A. County Department of Public Health ordered restaurants to close outdoor dining, among other measures meant to control the virus’s spread. Officials with another county agency fired back: L.A. County Supervisors Janice Hahn and Kathryn Barger vowed in an op-ed that they would “fight this seemingly baseless restriction.”

This disunity within the local government helped fuel pushback from Angelenos who have rejected public health guidance, said Kim. “With the thousands of deaths we saw in this surge, particularly of people of color in the working class, that kind of not speaking with one voice is unconscionable.”

One unified message coming from the state and local health departments, however, is that “COVID fatigue” is behind the devastation of the winter surge, as Dr. Mark Ghaly, California’s health and human services secretary, recently told the Los Angeles Times.

This narrative claims that Californians, tired of isolation, gathered over the winter holidays, despite best efforts by public health departments to discourage such behavior. But Wallace said a major communications mistake committed by officials has been to focus on absolutist rules that say “you can’t do this and you can’t do that,” rather than providing risk reduction advice that more closely mirrors human behavior.

“The state and local system of public health has always been underinvested in. And that underinvestment is clearly being challenged by the pandemic now.”

~ Chris Hoene, executive director of the California Budget & Policy Center

“It’s very tough when our communities are used to celebrating,” said Charisse Bremond-Weaver, the president and CEO of the Brotherhood Crusade, a grassroots group in South Los Angeles. Bremond-Weaver said groups like hers tried to get the message out, but the government could have done a better job educating those communities on how to keep safe. For example, social media influencers on platforms like Instagram and Facebook can reach at risk Angelenos online in ways that a government website can’t. And pamphlets distributed at churches or inserted into food assistance boxes are more likely to resonate than a government press release, community organizers said.

Many of the systems rolled out by L.A. county and city governments to provide information and access to COVID-19 testing, vaccines and treatment are by design inaccessible to many of those who need them most, experts said. For example, receiving a COVID-19 vaccine at the Dodger Stadium mega-site requires online sign-up, a vehicle to drive up in and a home address for follow-up — challenges for Angelenos who are unhoused, bed-bound or don’t have access to a car or the internet. The federal government, under the new Biden administration, has opened mass vaccination sites at the Oakland Coliseum and California State University, Los Angeles, both of which offer walk-up options but otherwise have similar requirements and limitations in reaching those at highest need.

Some L.A. City Council districts, such as Marqueece Harris-Dawson’s District 8 and Curren Price’s District 9, have made efforts to overcome these issues, including by providing walk-up services and rapid results. (None of the 15 Los Angeles City Councilmembers’ offices responded to requests for comment, nor did Mayor Eric Garcetti’s office).

Money has also been a major obstacle. Los Angeles, like other local jurisdictions across the country, has been cash strapped throughout the pandemic due to the economic impacts of closures and limited assistance from the federal government, said Chris Hoene, the executive director of the Sacramento-based California Budget & Policy Center.

“The state and local system of public health has always been underinvested in. And that underinvestment is clearly being challenged by the pandemic now,” Hoene said.

To restart the flow of tax revenues, Los Angeles and other Californian districts have pushed forward with reopenings. But these attempts to jumpstart the economy have consistently been followed by COVID-19 spikes in low income communities of color, according to data analysis by the Advancement Project California. For example, Los Angeles County allowed nonessential retail businesses like malls to continue operating through the winter despite outbreaks, and with minimal fines for violations. And reopenings are forging ahead even though essential workers, who had initially been at the top of the state’s priority list for receiving vaccines, got bumped back in the line behind elderly Californians.

“People are dying and we’re concerned about whether we can eat dinner inside,” said Leslie Johnson, the vice president of organizational development for the South L.A. organization Community Coalition. “It feels like economic interests are being prioritized, and it’s really impacting our communities in devastating ways.”

* * *

Next Steps

As Los Angeles moves past its deadly winter surge and seeks to strengthen its response in devastated communities, grassroots organizers say they’re ready to take on a larger role.

“It’s easy for us to reach out to the community at large,” said Senait Admassu, executive director of the African Communities Public Health Coalition, one of the groups selected by Los Angeles County to help neighborhoods experiencing high case and death rates to connect with health and social services.

“There’s this big gap between the government and the communities,” Admassu said. But there are different ways to reach out through trusted messengers, and she hopes the Community Equity Fund will serve as a pilot program to prove the effectiveness of these alternative methods.

Earlier in the pandemic, community organizations worked directly with local government to distribute personal protective equipment (PPE) and cash assistance for undocumented Californians. Groups also provided consultation for ramped up social support programs, which they are advocating be expanded and bolstered by long-term solutions that can follow up on temporary measures. For example, advocates are calling for rent and mortgage relief for those currently protected by the temporary eviction moratoriums at the state and local levels, as well as hotel vouchers, like those distributed through Project Roomkey, for low income Angelenos who contract COVID-19 and need to isolate themselves outside of their home.

However, the Los Angeles county and city governments didn’t fully utilize the robust network of established community organizations that have been built up over several decades, unlike San Francisco, which quickly coordinated a hyperlocal response through partnerships with groups on the ground.

Los Angeles County’s first major pandemic partnership with grassroots groups was the Community Health Worker Outreach Initiative launched last October and recently extended with CARES Act pandemic relief funding from the federal government.

The newly launched Equity Fund was supposed to start before the winter surge too. But community organizers said that government bureaucracy, including onerous contracting regulations and delays acquiring funding, slowed its start. The county did not comment on the project’s launch.

Los Angeles County will give 51 groups between $100,000 and $500,000 each, along with training and other resources. In return, the organizations will educate their communities and guide them to services. To do so, the groups will hire people directly from the affected communities.

Both of Los Angeles County’s community-based programs are being funded by private foundations and coordinated through two major nonprofit organizations, California Community Foundation and Community Partners.

If successful, this approach to funding communities to do their own outreach could be a model for statewide implementation, said John Kim, whose Advancement Project California calls the proposal an “Equity Corps.”

“We may likely have another surge… and are currently having a lot of problems around equity and vaccinations,” Kim said. “For a lot of these communities, this Equity Corps can be absolutely critical in this next leg of the race.”

Copyright 2021 Capital & Main

-

Striking BackApril 10, 2025

Striking BackApril 10, 2025USC Follows Amazon and Musk’s SpaceX in Calling Labor Board Unconstitutional

-

Latest NewsApril 9, 2025

Latest NewsApril 9, 2025Democratic and Republican Lawmakers Work to Undermine Voter-Backed Wage and Sick Leave Laws

-

Latest NewsApril 28, 2025

Latest NewsApril 28, 2025A Majority of Californians Support Affordable Health Care for Undocumented Immigrants, Polls Show

-

Latest NewsApril 11, 2025

Latest NewsApril 11, 2025California Showdown Over Medicaid as GOP Approves Massive Cuts

-

Column - California UncoveredMay 5, 2025

Column - California UncoveredMay 5, 2025How Did Farmers Respond When the Trump Administration Suddenly Stopped Paying Them to Help Feed Needy Californians?

-

Column - State of InequalityApril 11, 2025

Column - State of InequalityApril 11, 2025California State University’s Financial Aid Students Learn Chaos 101

-

The SlickApril 30, 2025

The SlickApril 30, 2025Fracking-Powered Crypto Mine in Pennsylvania Shuts Down Without Word to Regulators

-

The SlickApril 16, 2025

The SlickApril 16, 2025In Colorado, Gas for Cars Could Soon Come With a Warning Label