Living Homeless in California

Living Homeless in California: To Health and Back

One health-outreach group’s mandate is to get homeless people into sustainable living situations. Even after a client is placed in permanent housing, the team will follow up and, ideally, get the person to regularly visit a clinic.

Doctor: “Some medical conditions won’t get better until a person is housed. How do you store diabetes meds without a fridge?”

The 2018 Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority estimates that about 53,000 homeless people live in Los Angeles County, a slight drop that reverses a significant six-year surge. Their backgrounds are as varied as Los Angeles itself. Some are in shelters. Many more live in cars or in tents, or in any variety of unpermitted spaces. You wouldn’t necessarily know who’s homeless just by looking at them, as I discovered on a ride-along with a multidisciplinary outreach team in March.

The team is part of the Judy and Bernard Briskin Malibu/Pacific Palisades Homeless Project, which was launched in January 2017 to fund health care, temporary housing and case management in Malibu and Pacific Palisades, as part of a continuum of care for the most vulnerable homeless, usually those with medical concerns.

Also Read These Stories

I rode in a van with two professionals from the Venice Family Clinic, Dr. Coley King, DO, the clinic’s director of homeless services, and a psychiatrist, Dr. Wes Ryan. A social worker from partner homeless service agency the People Concern, Alex Gittinger, rounded out the team.

“Some medical conditions won’t get better until a person is housed,” King said. “How do you store diabetes meds without a fridge?”

The group’s mandate is to get people into a sustainable living situation, whether it’s nearby – super expensive – or in the San Fernando Valley or Inland Empire. Even after a client is placed in permanent housing, the team will follow up and, ideally, get the person to regularly visit the clinic.

Some of their clients obtain temporary housing through vouchers that pay for residential motels. The funding is limited and, as King puts it, “super complicated,” but is often a combination of money from the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) and Housing Authority of the City of Los Angeles (HACLA). The team has to be judicious with who gets a voucher for temporary or permanent housing, especially on Los Angeles’ Westside.

A tan and wiry 56-year-old, Michael was hit by a car while riding his bike on PCH. He insisted on using painkillers indefinitely.

“We don’t just drop people off at an apartment,” Gittinger said. “People who have been out on the streets for decades need continuous care to transition into living indoors [and] a new community, to build a network of friends, to become responsible with paying rent and utilities.”

The afternoon’s first stop was a small but clean Santa Monica motel where Michael was living while he recovered from injuries. A tan and wiry 56-year-old, Michael was hit by a car while riding his bike on Pacific Coast Highway in Malibu. It wasn’t his first time. He had a titanium rod in one leg from another hit-and-run on PCH. As Dr. King took his blood pressure, he reminded Michael that he has to be weaned off pain meds to avoid getting addicted.

Michael walked with a bamboo cane topped by a plastic golf ball and insisted on using painkillers at night — indefinitely. Dr. King warned against getting hooked, telling Michael that the voucher money for the medication in question would run out soon. Michael acquiesced and took a blister pack of new, less addictive meds.

After taking his vitals, King brought Michael to the Ocean Park Community Center in Santa Monica, where a nurse gave him a B12 injection. There, King and one of the center’s coordinators tried to convince him to consider one of the 70 beds in the OPCC shelter, noting that funding for his motel room will also soon run out.

Social Worker: “The first time I say, ‘I’m Alex and I do outreach,’ they shout at us to go away. And beer cans fly. But we keep showing up.”

“I’m too old to be around people who annoy me,” Michael replied. When King dropped Michael back at his motel, the injured man signed a form for $200 cash and a $200 EBT card, which will have to last him a month.

“You can buy a raw chicken with an EBT card but not prepared food,” King said, on his way to the next client. “How does that make sense? None of these places has a kitchen.”

At another small residential motel in Santa Monica, I met Dennis, a Vietnam vet in his 60s who’s bedridden with a serious leg wound in his shabby but livable room. He let me photograph him, but didn’t want to talk. While Dr. King took his vitals and asked him about his recent flu, Gittinger told me the Malibu team has been visiting Dennis for months, since they found him in an encampment in the bushes of Zuma Beach.

“Dennis didn’t want anything to do with us in the beginning, but we kept coming and bringing food,” Gittinger said.

Dennis is linked to the Veterans Affairs hospital in West Los Angeles, but didn’t like the organization’s red tape. He needed some consistency, someone to come to him, Gittinger said.

“We get to know the residents and the homeless population in an area, and it’s a small area so we’re not spread too thin,” Gittinger said. “We work with the sheriff, the city and over time we have found the hot spots. It’s all about building relationships. It may take 50 engagements with someone. The first time I say, ‘I’m Alex and I do outreach,’ they shout at us to go away. And beer cans fly. But we keep showing up.”

A secluded Zuma Beach encampment is called “Margaritaville” because it seems like a good spot for a college party. But nobody is partying.

Dennis is on a short list for senior housing in the Inland Empire. If it works out, he will be living with a friend he met in an encampment in Malibu, and will be permanently housed for the first time in more than two decades.

Our next stop was a Zuma Beach encampment of a half-dozen men in the high scrubby bushes near the parking lot. The location was secluded and if you’re homeless and living outside, you would probably want to crash there. The team called it “Margaritaville,” because it seemed like a good location for a college party. But nobody was partying.

At Margaritaville I met another Dennis — a beefy and well-groomed man in his 30s who told me he’s been at the encampment since last July 5 and that he wants to go back to school for photography. He was engaging and willing to talk, but vague about what led him to the beach. He had worked as a driver for Safeway and as a photographer, was an apprentice in the carpenters union for a while and had lived in San Francisco’s Tenderloin until he “couldn’t take the noise.” The beach may be a salubrious setting, and it even has outdoor showers – meant for swimmers, but the homeless population stealthily uses them too – but Dennis said it’s hard to fully relax. He worries that if he lets down his guard someone could take his things, and rats would come for his food.

“More and more are getting priced out. Either the rent has risen too much or they lost their job, and someone falls ill . . . The next step is a tent.”

Further down the coast highway, in Malibu, the team split up to check on several clients outside an upscale mini-mall. One was a man in his mid-60s. Tom – not his real name – was well-groomed and wearing khakis and a black polo shirt. He might have been a friend of the members of the team, hanging out with them in front of Starbucks — except that King was taking his blood pressure. Tom didn’t feel comfortable with my presence but I learned from the team that he was married and had owned a house, but has been living in his SUV for months and is suffering from chest pains, high blood pressure and general stress.

“He’s in denial about being homeless,” King said. The team has working on getting Tom a voucher for senior housing. They’re concerned that Tom’s age, health concerns and newness to being homeless make him more vulnerable to a life without shelter. A lot of the people living outdoors have been doing this for years and are very resourceful, knowing which establishments won’t hassle them for using the restroom. And sometimes, like the younger men at Zuma, they consider their experience as simply living off the land. That is, until their health fails or the weather goes bad.

There are about 30 people in the Venice outreach orbit, and about three dozen or so similar teams around Los Angeles County, all with different funding, each serving up to several hundred clients. “Nowhere near meeting the need of the entire homeless population,” Dr. King said.

Not everyone who experiences homelessness needs a team. But even those who pull themselves up by their bootstraps have relied on the kindness of strangers.

Gittinger said he looks at homelessness in the U.S. as a systemic problem, not an individual problem.

“More and more are getting priced out,” he said. “For whatever reason they can’t afford the rent anymore. Either the rent has risen too much or they lost their job, and someone falls ill. And with their last savings they may buy an RV or a van, and they try to keep it up. Then the van gets ticketed or towed and impounded, and they can’t pay to get it back. The next step is a tent.”

Copyright Capital & Main

-

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 22, 2026

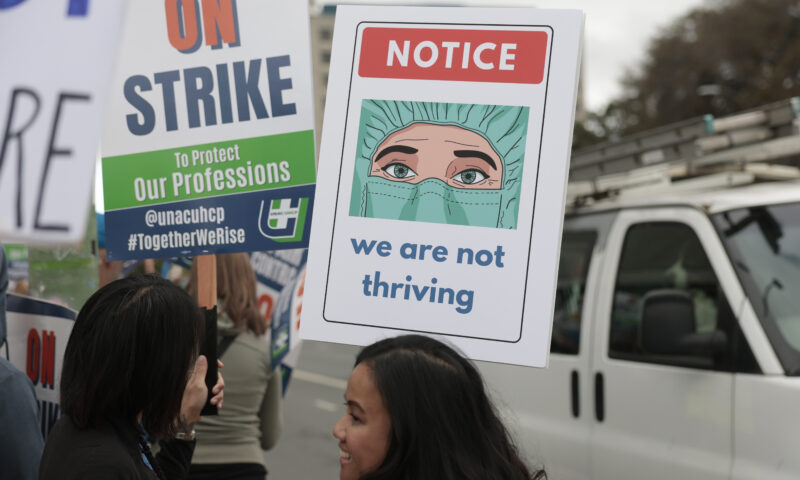

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 22, 2026On Eve of Strike, Kaiser Nurses Sound Alarm on Patient Care

-

Latest NewsJanuary 22, 2026

Latest NewsJanuary 22, 2026‘A Fraudulent Scheme’: New Mexico Sues Texas Oil Companies for Walking Away From Their Leaking Wells

-

The SlickJanuary 23, 2026

The SlickJanuary 23, 2026Yes, the Energy Transition Is Coming. But ‘Probably Not’ in Our Lifetime.

-

The SlickJanuary 27, 2026

The SlickJanuary 27, 2026The One Big Beautiful Prediction: The Energy Transition Is Still Alive

-

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 29, 2026

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 29, 2026Are California’s Billionaires Crying Wolf?

-

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026Amid the Violent Minnesota Raids, ICE Arrests Over 100 Refugees, Ships Many to Texas

-

Dirty MoneyJanuary 30, 2026

Dirty MoneyJanuary 30, 2026Amid Climate Crisis, Insurers’ Increased Use of AI Raises Concern For Policyholders

-

Featured VideoFebruary 4, 2026

Featured VideoFebruary 4, 2026Protesters Turn to Economic Disruption to Fight ICE