After Muhammad Jawaid, a Chicago rideshare driver, was assaulted by two riders this spring, he changed — in more ways than one. He’d been beaten by two young men who’d used an Uber profile of a young woman to request a ride, he said. At pickup, Jawaid said, the men had jumped into the backseat, hit Jawaid in the head with guns, knocked out several of his teeth, and tried to steal his car.

“I’m not the person [that] I used to be anymore, because it made a huge impact on my life,” Jawaid said.

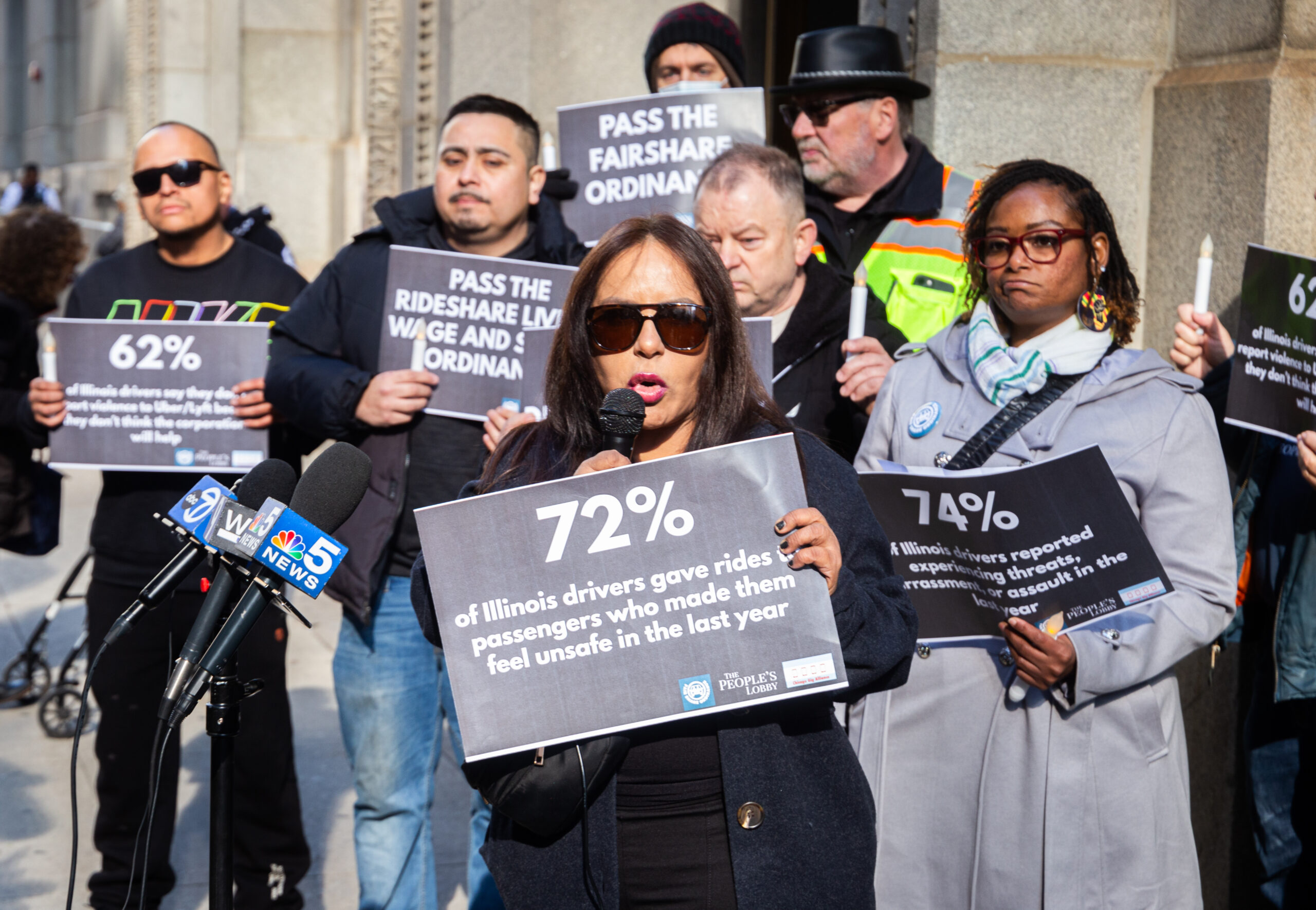

When Jawaid asked Uber to cover the cost of his injuries, he said, the company offered a fraction of his medical costs alone. Because Jawaid is not considered an employee but an independent contractor — a status both Uber and Lyft have fought hard to preserve for their drivers — he does not qualify for workers’ compensation. Without that protection, rideshare drivers can’t receive replacement wages when they’re injured on the job.

“This act of violence is deeply troubling,” Uber’s spokesperson said in response to questions about Jawaid’s case, adding that the company has spoken to Jawaid and worked with police to resolve the case. The company did not address questions about the cost of Jawaid’s medical care related to the incident. Representatives highlighted several in-app safety features for drivers and optional injury protection insurance that drivers can purchase for “less than $0.03 a mile.”

Frustrated by the company’s response, Jawaid did something new: He reached out to the Chicago Gig Alliance, a rideshare driver group that has been pushing for a city ordinance that would have required the rideshare companies to verify all passenger accounts and provide identity verification to drivers as they pick up passengers. His reason for contacting the group? “Maybe it would be helpful for other people,” he said. (The Chicago City Council tabled the proposed ordinance in June.)

Today, Jawaid’s experience is becoming more common — and not only among rideshare drivers. As workplace violence has risen over the last decade, it has driven an increasing number of workers to organize. Across the country, nurses and cashiers, drivers and food servers are fighting for a right that many take as a given: being safe from violence at work.

* * *

The clearest reason that more workers are fighting to end violence at work is that more workers are experiencing violence on the job.

Violent incidents at work have risen by nearly 20% since 2015, going from 34,750 that year to 41,440 in 2022, the most recent year for which statistics are available. Meanwhile, there is no federal workplace safety standard to prevent violence on the job. About two dozen states have proposed or enacted legislation to prevent workplace violence, but the problem persists across the country, per a review of bills and legislation tracked by BillTrack50.

“The experience of workplace violence is being felt most acutely by workers who already are in occupations where their wages have been suppressed,” said Jennifer Sherer, director of the State Worker Power Initiative at the Economic Policy Institute.

The push to address violence on the job appears to be strongest among service and care workers — and especially health care workers. Most of those jobs were not protected by wage and hour laws until the 1960s. In 2021-22, those workers experienced 86% of workplace injuries by another person, according to a Capital & Main analysis of Bureau of Labor Statistics data.

“Unionization in those sectors, I think it’s more important than almost any other,” said Sherer.

* * *

In New Orleans, for instance, nurses at University Medical Center New Orleans went on a one-day strike on May 1, and cited workplace violence as the key issue. Indeed, violence at work fueled worker unrest that led to a successful union election in December 2023, said Heidi Tujague, a registered nurse and UMCNO bargaining team member, via a union spokesperson. It has since been a core bargaining chip in the negotiations for their first contract, an effort that began in March 2024.

Nurses picket outside of University Medical Center New Orleans on May 1. Photo courtesy National Nurses United.

Nurses experience various kinds of violence on the job, ranging from pinches and slaps to being kicked in the stomach while pregnant and being choked with stethoscopes, said Jane Thomason, lead industrial hygienist of National Nurses United. They also experience violence far more frequently than many other workers. Health care workers experience violence at work nearly twice as often as workers in education, and 10 times as often as those in retail and food service, according to Bureau of Labor Statistics data. (Disclosure: National Nurses United is a funder of Capital & Main.)

Smaller surveys suggest that federal statistics reflect “a tiny fraction” of violence in health care, said Thomason. Nearly 82% of 1,000 nurses surveyed by National Nurses United in February 2024 reported at least one violent incident at work in the prior year.

“Workplace violence at UMC is a serious part of what we’re trying to address with our unionization,” Tujague said in a statement. “It’s part and parcel with safe staffing, another one of our key demands. When we’re safely staffed, it makes de-escalation easier.”

LCMC Health, the parent company of the University Medical Center in New Orleans, did not answer emailed questions from Capital & Main.

* * *

Violence at work is driving restaurant workers to organize, too. Such violence has become so prevalent that a video of it has gone viral on social media, becoming popular fodder that overshadows the impact on workers.

For three days starting on May 16, Waffle House employees across the South staged a protest over workplace violence and low pay at the chain.

For Waffle House workers, violence and harassment were part of the job until concerns over workplace violence reached the boiling point when a man forced his way behind the counter of a Marietta, Georgia, Waffle House in April. It was around 6 a.m., a Union of Southern Service Workers spokesperson confirmed. The man pushed an employee to the ground, then ran behind the counter and into the back office of the restaurant, the spokesperson said. He didn’t leave until the police arrived 20 minutes later and escorted him out. ((Disclosure: the Union of Southern Service Workers is a cross-sector affiliate of the Service Employees International Union, a financial supporter of Capital & Main.)

Store management appeared to laugh off the incident, said Melissa Steach, a server at the Marietta restaurant. Nothing changed, she said, until workers took action.

Waffle House did not respond to a request for comment.

Without a robust response from management or corporate leadership, Waffle House workers decided they were fed up. Workers from across the region delivered a list of demands to Waffle House offices and held a protest on the first day of the strike. They used the Marietta incident as a catalyst to repeat their ongoing demands for a $25 per hour minimum wage, safer working conditions (including security staff on site) and the end of a mandatory meal deduction policy.

Waffle House workers and members of the Union of Southern Service Workers protest workplace violence and low pay on May 16 in Atlanta. Photo courtesy USSW.

Even with companywide raises announced last year and working full time, Steach said she earns about $2,300 a month: $4.25 an hour in wages that come to roughly $680, and the rest in tips. She has been unable to afford a one-bedroom apartment or studio, both of which cost around $1,300 a month in Marietta, according to Zillow. For now, she lives in a motel and walks to work.

Following the strike, management did not hire security staff. Instead, they changed protocol on the Marietta store’s third shift, locking the store’s doors and limiting service to takeout in the wee hours of the morning, said Steach. For Steach, that decision has led to lower tips, she said.

It has also made Steach more willing to fight — even if she feels a little scared to speak up.

“I know how companies will react,” she said. “Even though it is against federal law to fire someone for organizing, it doesn’t mean they can’t.”

But having her fellow union members’ support meant a lot to her, she said. “I’m tired of looking over my shoulder and wondering, ‘Is this going to be the day that someone decides that they’re going to pull a gun on me?’” Steach said. “I’d like the public to understand that all work has dignity… We are all fighting for the same thing. We’re all fighting for that slice of comfort. That slice of stability. Security.”

Copyright 2025 Capital & Main

The SlickJanuary 23, 2026

The SlickJanuary 23, 2026

The SlickJanuary 27, 2026

The SlickJanuary 27, 2026

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 29, 2026

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 29, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026

Dirty MoneyJanuary 30, 2026

Dirty MoneyJanuary 30, 2026

Featured VideoFebruary 4, 2026

Featured VideoFebruary 4, 2026

The SlickFebruary 2, 2026

The SlickFebruary 2, 2026

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 5, 2026

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 5, 2026