The news for both climate change and economic inequality has been undeniably dire. In December the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s annual Arctic Report Card concluded that a critical cooling system around the North Pole may be breaking down, just the latest ominous survey about the existential threat of the climate crisis. On the economic front, a recent report by the Brookings Institution showed that 44 percent of American workers are stuck in low-wage jobs paying a median of $18,000 per year.

Addressing one of these crises is a monumental challenge for one nation; tackling both at once might appear to be insurmountable. But there are lawmakers, academics, and leaders in business and labor who believe that not only should the U.S. deal with both crises simultaneously, it must and it can. Indeed, a growing body of research indicates that many of the solutions to address the climate crisis and economic inequality are the same.

How a Green New Deal Could Grow High Wage Jobs

On a November day outside the U.S. Capitol, U.S. Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, (D-N.Y.), and Senator Bernie Sanders (D-Vt.) told a shivering crowd that they would be introducing legislation to invest $172 billion in retrofitting the nation’s public housing stock to improve energy efficiency, as part of a sweeping Green New Deal. “This bill shows,” they announced, “that we can address our climate and affordable housing crises by making public housing a model of efficiency, sustainability and resiliency.” The broad outline for a Green New Deal, endorsed by 60 representatives, made news for its climate change goals, including decarbonizing manufacturing and agriculture, upgrading all buildings to be energy efficient and building a “smart” grid. But the Green New Deal also addresses income inequality, acknowledging that the effects of climate change fall hardest on lower income people.

A September United Nations report endorsed the general framework for an international green new deal as a way of lifting up poor and vulnerable communities. It concluded that “achieving human well-being and eradicating poverty for all of the Earth’s people—expected to number 8.5 billion by 2030—is still possible, but only if there is a fundamental—and urgent—change in the relationship between people and nature.”

The Trump administration remains hostile to any efforts to cut back on fossil fuel extraction or consumption, and no Republican in Congress has embraced any renewable climate goals, let alone ones that benefit workers. Meanwhile, Democratic presidential candidates run the gamut of “green-blue” advocacy.

Where the Candidates Stand

Not only have all Democratic presidential contenders identified climate change as an urgent issue, many also recognize the intersection of environmental and economic impacts of climate change.

Joe Biden: In his campaign’s climate platform, Biden embraced the Green New Deal as a “crucial framework,” and pledged $1.7 trillion in spending over a decade, and $3.3 trillion in investments by state and local governments and the private sector. His policy agenda for rural America calls for expanding a program that pays farmers for techniques that store carbon in the soil. He also calls for support for economically impacted communities. Biden signed a No Fossil Fuel Money pledge.

Joe Biden: In his campaign’s climate platform, Biden embraced the Green New Deal as a “crucial framework,” and pledged $1.7 trillion in spending over a decade, and $3.3 trillion in investments by state and local governments and the private sector. His policy agenda for rural America calls for expanding a program that pays farmers for techniques that store carbon in the soil. He also calls for support for economically impacted communities. Biden signed a No Fossil Fuel Money pledge.

Elizabeth Warren: When Washington Gov. Jay Inslee exited the race, Warren adopted his aggressive $5 trillion investment in green research, manufacturing and exporting. Her environmental justice plan includes investments of “at least $1 trillion” to vulnerable communities most impacted by climate change. Warren’s agriculture plan would incentivize farmers to invest in sustainable farming practices that reduce carbon emissions. Her “Blue New Deal” plan for the oceans would fast-track permitting of offshore wind energy while phasing out offshore drilling for oil and gas. She also calls for electrification of ports to reduce local air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions.

Elizabeth Warren: When Washington Gov. Jay Inslee exited the race, Warren adopted his aggressive $5 trillion investment in green research, manufacturing and exporting. Her environmental justice plan includes investments of “at least $1 trillion” to vulnerable communities most impacted by climate change. Warren’s agriculture plan would incentivize farmers to invest in sustainable farming practices that reduce carbon emissions. Her “Blue New Deal” plan for the oceans would fast-track permitting of offshore wind energy while phasing out offshore drilling for oil and gas. She also calls for electrification of ports to reduce local air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions.

Bernie Sanders: Last year Sanders unveiled an ambitious climate plan promising to declare climate change a national emergency and put the Green New Deal into action by investing $16.3 trillion over 10 years — far more than what other candidates are proposing. He promises 20 million new jobs in clean energy, energy efficiency and technology. He also vows to transition to more sustainable farming and to break up big agribusinesses. He says his plan can get 100 percent renewable energy by 2030 and complete decarbonization by 2050.

Bernie Sanders: Last year Sanders unveiled an ambitious climate plan promising to declare climate change a national emergency and put the Green New Deal into action by investing $16.3 trillion over 10 years — far more than what other candidates are proposing. He promises 20 million new jobs in clean energy, energy efficiency and technology. He also vows to transition to more sustainable farming and to break up big agribusinesses. He says his plan can get 100 percent renewable energy by 2030 and complete decarbonization by 2050.

Pete Buttigieg: Last year Buttigieg released a climate program touting his own “bold and achievable Green New Deal,” claiming a zero-emissions economy was achievable by mid-century. He pledged to create 3 million new jobs through a 10-year, $200 billion investment in retraining workers displaced by a decarbonizing economy. He also proposed a Climate Corps service program to help communities with sustainable development.

Cory Booker: Booker’s climate plan highlights environmental justice and includes a $3 trillion investment in programs to move the nation to 100 percent carbon-free electricity by 2030, helped by grants for regional high-speed rail and electric buses. Booker wants to end fossil fuel subsidies, phase out fracking, ban new fossil fuel leases on federal lands and revoke federal approvals for major oil pipelines. He also supports tax credits for wind, solar, energy storage and electric vehicles. His housing plan encourages more efficient housing and communities that reduce reliance on cars.

Cory Booker: Booker’s climate plan highlights environmental justice and includes a $3 trillion investment in programs to move the nation to 100 percent carbon-free electricity by 2030, helped by grants for regional high-speed rail and electric buses. Booker wants to end fossil fuel subsidies, phase out fracking, ban new fossil fuel leases on federal lands and revoke federal approvals for major oil pipelines. He also supports tax credits for wind, solar, energy storage and electric vehicles. His housing plan encourages more efficient housing and communities that reduce reliance on cars.

Amy Klobuchar: Last year Klobuchar released a “Plan to Tackle the Climate Crisis” that promises to quickly restore climate and clean energy policies rolled back by Trump. She sets a goal of zero emissions by 2050, similar to the Paris accord goals, and proposes a $1 trillion energy infrastructure package that includes grants and tax credits to encourage investment in clean energy and efficiency. Klobuchar co-sponsored the Green New Deal resolution in Congress but hasn’t embraced it in her own climate plan.

Andrew Yang: Yang’s climate plan proposes investing $4.9 trillion over 20 years to deal with climate change, $400 billion of which would fund federal campaigns to reduce the influence of fossil fuel companies. His goal of net zero emissions across the economy by 2050 would be achieved by federal rules requiring new buildings to have net zero emissions by 2025, and all new car models to be zero emissions by 2030. He would aim to get the country to 100 percent zero-emissions electricity by 2035, while mandating all transportation sectors to be net zero by 2040. Yang is the only Democratic candidate backing investment in new nuclear technologies.

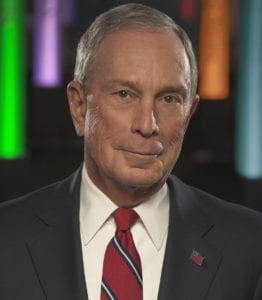

Michael Bloomberg: The newest entry in the race, Bloomberg has suggested that a Green New Deal could not happen with a Republican-controlled U.S. Senate. Like the other Democratic candidates, he has embraced 100 percent clean energy by 2050, with an interim goal of cutting emissions 50 percent by 2030. He said he would work to replace the remaining U.S. coal plants with clean energy, and work with community leaders and local officials to ensure that community transition plans are in place and “prioritize the frontline communities that have suffered most from coal pollution or have been left behind in the transition to clean energy.”

Michael Bloomberg: The newest entry in the race, Bloomberg has suggested that a Green New Deal could not happen with a Republican-controlled U.S. Senate. Like the other Democratic candidates, he has embraced 100 percent clean energy by 2050, with an interim goal of cutting emissions 50 percent by 2030. He said he would work to replace the remaining U.S. coal plants with clean energy, and work with community leaders and local officials to ensure that community transition plans are in place and “prioritize the frontline communities that have suffered most from coal pollution or have been left behind in the transition to clean energy.”

Tom Steyer: Climate change has been a major focus of Steyer’s money and activism for years. As a candidate his extensive “Justice-Centered” climate plan includes declaring climate change a national emergency and support for Green New Deal legislation. The plan calls for 100 percent clean electricity and net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2045 across all sectors. Steyer promises to build a “Civilian Climate Corps” funded with $250 billion in bonds over a decade and create 1 million jobs. His plan also commits $50 billion to wages and benefits lost by fossil fuel workers. And he has vowed to commit $2 trillion over a decade to make infrastructure more climate-friendly and resilient.

* * *

As long as Republicans control the White House and one branch of Congress, states that want an equitable transition to clean energy will have to go their own way. California has picked up the torch that congressional Republicans refuse to even touch. And at least one labor group is embracing, not fighting, a Green New Deal. In March, the Los Angeles County Federation of Labor touted the broad outline of a Green New Deal that would benefit the environment and the economy. “Economic inequality and threats to the environment are deeply intertwined, and a Green New Deal framework is vital to fighting both,” the statement read. “We don’t have time to pit jobs against the environment. We never did.”

There are some individual examples of transitions that could be replicated or serve as models. Sitting between rugged hills and the ocean on the central coast, Diablo Canyon in 2016 was ordered to close by its operator, Pacific Gas & Electric (PG&E). But the utility also asked Governor Jerry Brown to not leave its employees out in the cold. In signing legislation to close Diablo, Governor Brown agreed that the state would cover a $350 million tab for employee retention and $85 million for community impact.

In production and manufacturing, electric bus startup Proterra recently allowed its 60 City of Industry employees to join the United Steelworkers Union (USW). Dave Campbell, secretary-treasurer of USW Local 675, told Capital & Main that although Proterra members have yet to agree to a contract, doing so could represent a promising model for how union jobs fit into a decarbonizing economy. “Our members make two times as much as those of non-union workers in the electric vehicle industry,” he said.

Campbell admits that many unions that have relied on fossil-fuel-related jobs are hunkering down rather than looking forward. “Many are oblivious,” he said, adding that some, when they saw the timeline of how California planned to decarbonize by 2045, said, “Oh my God!”

“I do know these policies at the state, county and city [levels] will take customers away from refineries,” Campbell continued. “The days of refineries are numbered. We don’t think it will immediately affect us, but we must start to prepare for it. We’re trying to figure out the plan.”

Labor advocates say two types of agreements can bring high quality jobs that will help the state reach its climate goals. Project labor agreements mandate bargaining between management and construction unions over development of solar farms, retrofitting, and other green economy projects. They generally require that work pay prevailing—typically, union—wages on all public projects, and sometimes require projects to hire new workers from union or joint union-management apprenticeship programs. Community workforce agreements can also be forged, to help employ workers directly from local communities where the construction will occur.

“The building trade has been supportive of climate policy and they helped write the renewable standards because they saw their future in it,” said Carol Zabin, director of the University of California, Berkeley, Labor Center’s Green Economy Program. But Zabin added that labor is not monolithic, and not all industries are rowing in the direction of the state’s climate goals. Furthermore, Zabin is concerned about the future of the trucking industry, both with regard to its ability to reduce greenhouse gases and to support its drivers.

“We have port truckers doing short haul, which is a source of pollution and greenhouse gasses. This uses independent contractors, who must lease their trucks, and they bear the cost of climate policy, complying with clean truck standards. These are bad jobs that can’t implement [climate] policy. It’s a lose-lose situation right now.”

A recent report on decarbonizing California’s buildings from the University of California, Los Angeles, Luskin Center for Innovation projected an increase in renewable construction activity, electricity generation and transmission until 2045. In a webinar explaining the study’s findings, author Betony Jones said these new jobs would more than offset losses in oil and gas distribution and production, but it wasn’t yet clear whether they would all be high wage jobs. She recommended that the state workforce board come up with something like a “G.I. Bill, to retrain workers and give a range of good jobs to choose from.”

* * *

Utilities All Over the Map

California’s utilities are not all on board for a decarbonized future, let alone for a just transition for their oil and gas workers. In an email to Capital & Main, a PG&E spokesperson touted the company’s green credentials, claiming it had achieved “California’s 2020 renewable energy goal three years ahead of schedule.” But in the email the PG&E spokesperson also said, “Natural gas would remain an important fuel for customers beyond 2045” and did not address any plan for how to move workers phased out of oil and gas into clean energy jobs. However, earlier this year, at a Berkeley City Council meeting to discuss a ban on natural gas in new construction in that city, PG&E, which delivers natural gas and electricity to Berkeley residents, said it supports local government policies that promote new all-electric construction.

“We welcome the opportunity to avoid investments in new gas assets that might later prove underutilized as local governments and the state work together to realize our long term decarbonization objectives,” Darin Cline, a PG&E manager for public affairs and government relations, said at the city council meeting in July.

Sempra Energy, parent company of San Diego Gas and Electric and Southern California Gas Company (SoCalGas), did not respond to requests for information about “just transitions.” SoCalGas, for its part, has been doubling down on its commitment to natural gas by using a front group to persuade communities to not abandon gas in the near future. SoCalGas employees, claiming to be concerned citizens, not company representatives, have showed up at community meetings touting the corporation’s line that state efforts to electrify buildings would take away their freedom of choice.

“SoCalGas is in denial and opposition [to decarbonization],” said Rachel Golden, deputy director of the Sierra Club’s Building Electrification program. Golden suggested that the state should step in and make companies like SoCalGas get on board with not only the 2045 clean energy goals, but in creating jobs to get there. “Government has a big role to play on Green New Deal and inequality. It shouldn’t be left to the market. Government needs to sketch out what does each sector look like in 2045 — energy, construction and the grid. Gavin Newsom needs to hold public stakeholder meetings throughout the state and . . . discount what SoCalGas is saying.”

Golden was the lead author in a recent Building Electrification Plan that would not only lower energy bills and reduce the cost of new housing, but also “create roughly 100,000 new jobs in construction, HVAC [heating, ventilation and air conditioning] installation, electrical work, energy efficiency and load-management services.”

Golden told Capital & Main that major job losses in the oil and gas industry are still at least a decade away, but industry shouldn’t become complacent about the seemingly large time window. “There are many ways to go about the transition, but we must incentivize workers to transition now.”

Photo credits: Michael Stokes (Biden); Elizabeth Warren for President (Warren); Joanne Kim (Sanders); U.S. Senate (Booker, Klobuchar); Bloomberg Philanthropies (Bloomberg); Gage Skidmore (Yang, Steyer).

Copyright Capital & Main