Labor & Economy

New Hope for Parents Who Struggle to Find Affordable Daycare

Co-published by TIME.

Alissa Quart reports on how parents are navigating the increasingly expensive and unequal world of daycare.

Co-published by TIME

Zoe Hanson, the young mother of a year-old infant, was feeling down: She and her husband Scott had just moved to Pacifica, near San Francisco, to an apartment in a “crumbly house” that, nevertheless, at $3,000 a month, was untenably expensive. She didn’t have a job and didn’t know where to put her child while she looked for work.

Hanson, 29, began her hunt in a basic—albeit desperate—fashion. She Googled “daycare” and her new suburban town in quotes. Her search turned up only three candidates, which she called to find out their costs. “Daycare centers don’t have a lot of pricing transparency,” she says.

She then applied to them all; there were no spots. So she started looking further afield, near where her potential job might be in San Francisco. “No one had any openings,” she recalls. It seemed that in Pacifica there were “6,000 kids for only 3,000 daycare spots,” she says. Without daycare, she couldn’t even look for work.

Hanson and other parents are on the receiving end of an emerging type of unequal system that could be called daycare inequality.

Hanson’s problem is a familiar one to many mothers who would like to return to the workforce: For the most part, quality daycare is both affordable and accessible for the relatively wealthy only. In 31 states and Washington, D.C. — the yearly cost of an infant in a daycare center full time is higher than yearly tuition and fees at a state public college.

Plus, it’s scarce nationwide: Colorado’s licensed daycare spots only meet the needs of a quarter of the state’s young children. In Minnesota, the number of in-home childcare providers in three counties has declined by more than 17 percent in the last five years, leading to an extreme shortfall. Ditto in North Dakota, which also suffers from a shortage of child care providers. And the spots that do exist are hard to find.

On August 8, Republican Presidential candidate Donald Trump announced a plan to allow parents to “fully deduct the average cost of childcare spending from their taxes.” (Currently, parents can deduct up to $6,000.) Trump’s plan has been found to mostly favor high earners who paid enough in taxes to claim back the full outlay for childcare.

Meanwhile, Hillary Clinton wants no household to pay more than 10 percent of its income on childcare, using tax credits and taxpayer subsidized daycare. This would help low-earners but may not erase the problem of insufficient supply.

The market has stepped up to help wealthy parents. There are a host of new services to help them balance their work and family lives, including childcare concierges. “Life would be so much easier if we had personal assistants for our children,” says the website for one such company, Kid Care Concierge, of Bridgewater, New Jersey. It offers a “personalized and exclusive concierge service firm, establishing a harmonious work-life balance for busy families.” Benefits include “kid care assistants” who “manage your children’s busy schedules.”

If that’s a bit much, slightly more modest packages are provided by individual consultants, such as Nicole Van Giesen, a “personal childcare concierge” who, for $250, will recommend a preschool or a daycare for a child in New Jersey’s suburbs. And Daycare Discover in Chicago boasts on its site: “Traditionally, it takes 45 hours to find a daycare. We’ll do it for you for $150.”

For kids with packed schedules typical of the upper middle class, there’s even an on-demand ride-and-care service for children in Southern California and the Bay Area called Zum, which resembles Lyft and ferries children from 5 to 15 to and from school or, say, team practice, for rides that start at $16 for a kid, with childcare pre- or post-rides at $12 per half hour.

It’s part of a new America described in Arlie Russell Hochschild’s book The Outsourced Self: What was once part of private life is now outsourced, and then sold back to desperate consumer parents as high-end expertise.

Zoe Hanson could not afford any of these, but she did get help. She found her child a place in a daycare located through NurtureList, which she came upon when one of her acquaintances told her to try a “Golden Gate” mothers’ group. NurtureList is based in the Bay Area, a start-up with seed funding. The site offers a search engine filled with facilities and fastidious school profiles. Yin Li, NurtureList’s founder, is a San Francisco entrepreneur who says she wants to connect with “childcare providers and give them a way to get discovered and stand out to parents.”

In addition to listing daycare openings geographically, the site writes up new schools and, say, unusual programs, like ones that take place outside of preschool. NurtureList and similar sites, such as New York City’s free, public school site, InsideSchools, offer a vision for equalizing childcare access, a central clearing house that not only helps parents in a bind, but might motivate more childcare centers to open their doors.

Hanson plugged potential neighborhoods and the age of her daughter into the site to try to locate an available daycare spot. “I was assuming I couldn’t afford anything but an institutional setting for my daughter—a big gray room full of toddlers,” she said. But the Hansons quickly found a place in a daycare center in San Francisco’s Mission District that was Spanish immersion, with home-cooked meals. At nearly the same time, Hanson also got a job, as a studio and marketing coordinator at a design and architecture practice.

So far, however, such databases are only available in wealthy and wired places like San Francisco and New York. But what if free online daycare finders could be popularized in parts of the country where problems accessing daycare availability are also hampering the workforce, as a modest kind of “inequality hack”?

“If these daycare sites were free and accessible to everyone, the transparency of childcare would increase,” says Hanson. “When you are a poor person, you are looking for daycare, maybe you don’t have a computer, so you are going online in the library or on your phone. And most centers don’t opt to have their pricing availability, either.”

“Imagine,” she adds, “if you could see [through an app or website] all the daycare openings and costs across the country. How helpful this would be!”

This story was produced with support from the Economic Hardship Reporting Project.

Alissa Quart is the author of three nonfiction books: Branded, Hothouse Kids and Republic of Outsiders. She has written features for the New York Times Magazine, The Atlantic, The Nation and other publications, and is executive editor of the Economic Hardship Reporting Project.

-

Latest NewsJanuary 8, 2026

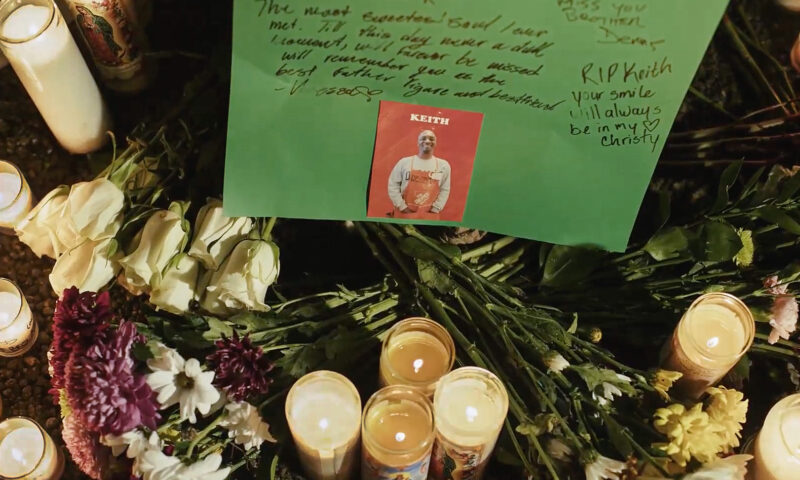

Latest NewsJanuary 8, 2026Why No Charges? Friends, Family of Man Killed by Off-Duty ICE Officer Ask After New Year’s Eve Shooting.

-

Latest NewsDecember 29, 2025

Latest NewsDecember 29, 2025Editor’s Picks: Capital & Main’s Standout Stories of 2025

-

Latest NewsDecember 30, 2025

Latest NewsDecember 30, 2025From Fire to ICE: The Year in Video

-

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 1, 2026

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 1, 2026Still the Golden State?

-

The SlickJanuary 12, 2026

The SlickJanuary 12, 2026Will an Old Pennsylvania Coal Town Get a Reboot From AI?

-

Latest NewsJanuary 6, 2026

Latest NewsJanuary 6, 2026In a Time of Extreme Peril, Burmese Journalists Tell Stories From the Shadows

-

Pain & ProfitJanuary 7, 2026

Pain & ProfitJanuary 7, 2026Trump’s Biggest Inaugural Donor Benefits from Policy Changes That Raise Worker Safety Concerns

-

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 8, 2026

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 8, 2026Can California’s New Immigrant Laws Help — and Hold Up in Court?