Culture & Media

The Power of the Poster

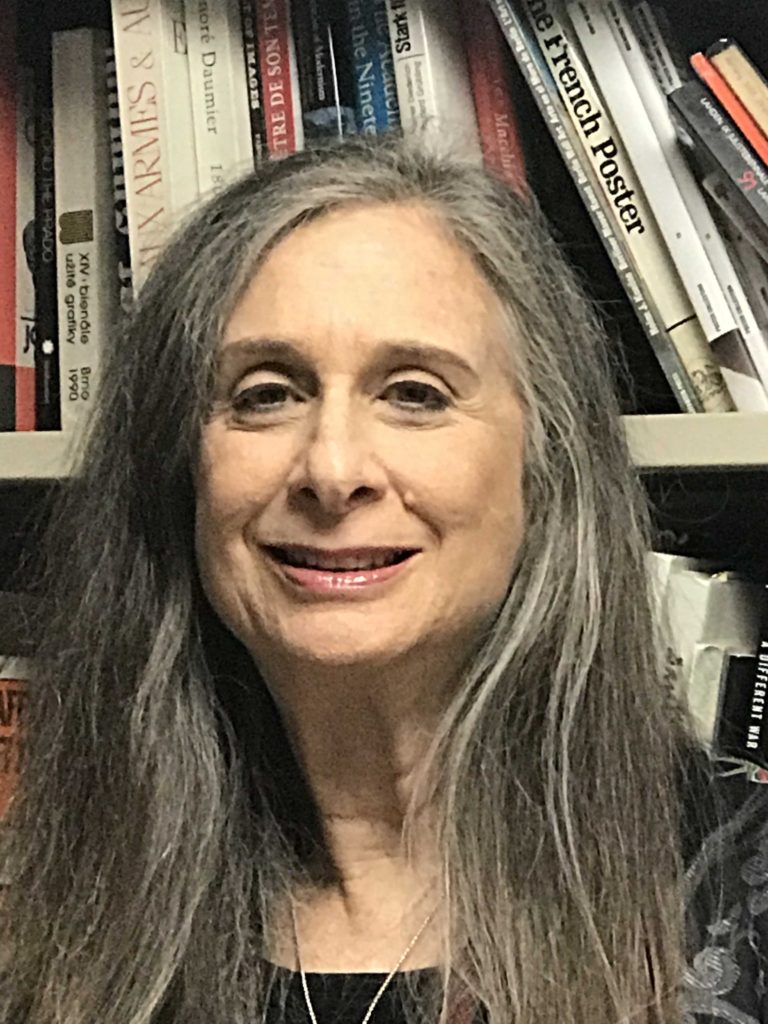

Carol Wells, the founder of the Center for the Study of Political Graphics in Los Angeles, talks to Capital & Main about the enduring power of political art.

Carol Wells remembers the exact moment she discovered her calling. An art historian at the time, she was on a trip to Nicaragua with her friend David Kunzle, a UCLA art history professor, who was collecting political posters to add to his burgeoning collection. While staying with friends, Wells watched a neighbor’s 8-year-old son approach a poster on the wall, stare at it intently, and then start to silently mouth the words. Wells was struck by how engaged the boy was. “In that moment I became obsessed with collecting posters.”

Carol Well, executive director of CSPG

Now over 40 years later, Wells is the founder and executive director of the Center for the Study of Political Graphics in Los Angeles. Wells has amassed approximately 90,000 posters, building one of the largest collections of its kind in the world. The Center shares its collection with the public in part through curated exhibits. This year the CSPG has produced Feminae: Typographic Voices of Women by Women and its latest is To Protect & Serve? Five Decades of Posters Protesting Police Violence, running through July 15 at the Mercado La Paloma in downtown Los Angeles.

Since that encounter in Nicaragua in 1981, Wells’ obsession with collecting posters hasn’t waned. In CSPG’s nondescript West L.A. office space, Wells pulls out poster after poster, lecturing passionately on the backstory and cultural impact of each, including one that superimposes text from a New York Times interview with a shocking image of the My Lai massacre (“Q: And babies? A: And babies.”). Recently, she managed to sit down with C&M to discuss her passion.

Capital & Main: So, you were an art history professor, you happen to see a kid on a trip, and suddenly your life was changed forever?

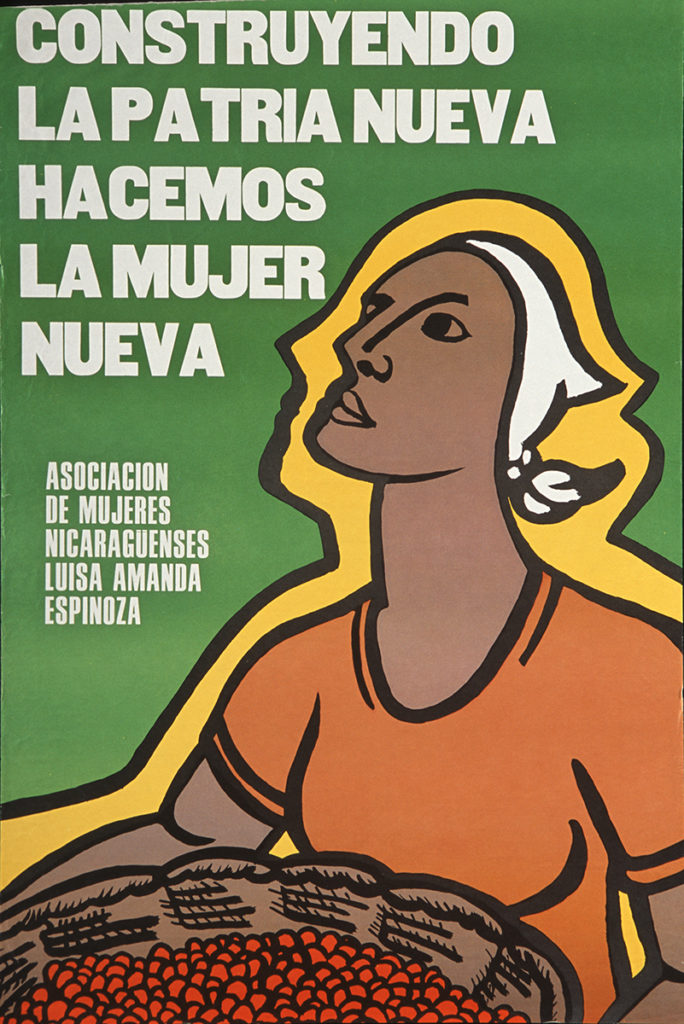

From the Asociación de Mujeres Nicaragüenses Luisa Amanda Espinoza

Nicaragua, 1981

Carol Wells: Yeah, I’m in Nicaragua alone in the living room with this kid. He’s looking around, and all of a sudden, he sees the poster. It was pretty big, bright green, a thick outlines of a woman holding a big basket of coffee beans. And the text in Spanish said, “In constructing the new country, we are becoming the new woman.” I see him walk over to the poster and I’m watching him mouth the words. It was a pretty sophisticated concept, so I doubt he figured it out. But I literally had this epiphany: “Oh my God. That’s how posters work.” You’re going about your daily life, and all of a sudden something breaks through the bubble, and it grabs your attention. It’s the graphic, it’s the color, it’s the combination, and it pulls you out of your head and into that poster and it makes you ask a question. “Why is this here? What is this about? What does this mean?” And every time you ask a question, you’re a different person than you were before you asked the question.

How many posters do you get a year?

We get between two to five thousand a year donated from all over the world. The bulk of our collection is [from] 1945 and later.

I assume technology has probably hurt the art form, but has it helped get the messages out?

Most people think that, and it’s actually not true. Since the internet age started, there’s actually a poster renaissance of works on paper. Because you can’t walk with your computer monitor in a demonstration. You can’t plant your monitor on your lawn.

And you can’t put a laptop on the wall…

Exactly. You want to hear a really great story? Truthdig.org published a cartoon [made by] a political cartoonist named Mr. Fish. It was during the Arab spring, and he had superimposed Che Guevara with the stylized beard and King Tut’s face, but it had Che’s beret. And it [was titled], “Walk like an Egyptian.” So, it was a reference to the music, but [it was also] a reference to what was going on the streets of Cairo. I sent it out as our poster of the week to 9,000 people. The very next day, somebody took a photograph on the street of Cairo, with somebody holding a piece of paper with that image on it. A poster can literally go around the world and people will print it out.

What struck me in viewing your exhibits is how many of these posters could still be used today, not only artistically but also, sadly, in the timeliness of their messages.

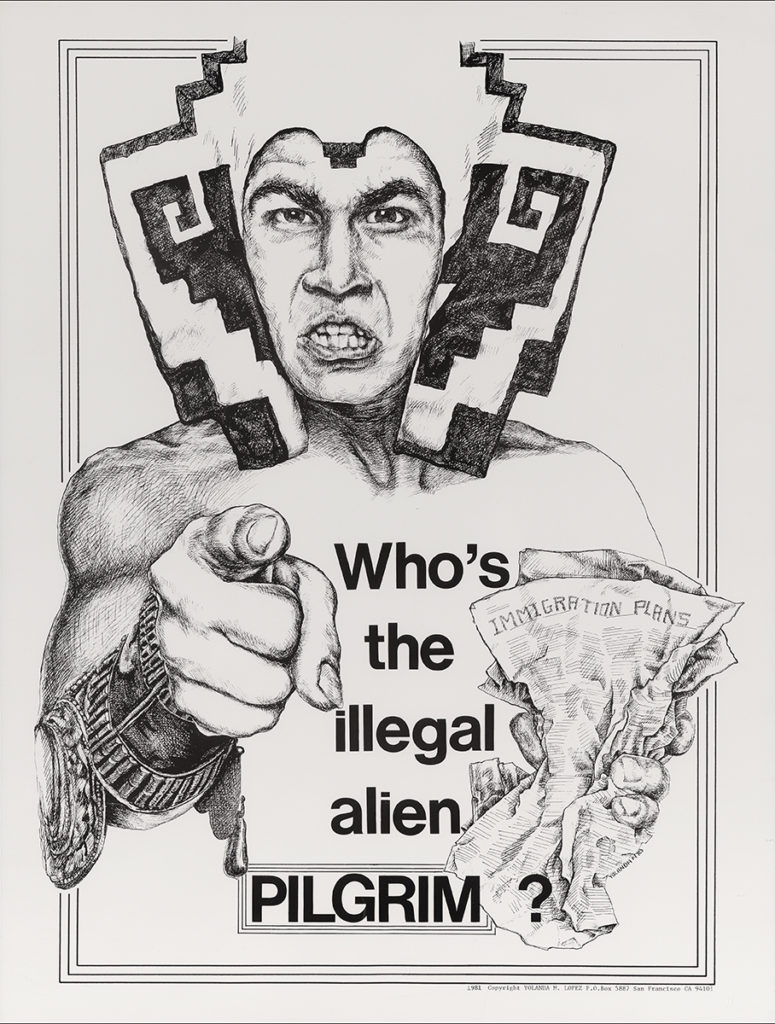

“Who’s the Illegal Alien, Pilgrim?”

by Yolanda M. Lopez, 1981

We had this fabulous poster by Yolanda Lopez, a Bay Area artist, which she first did in 1978. It depicts a young man in Aztec garb pointing a finger like Uncle Sam saying, “Who’s the illegal alien, PILGRIM?” And it’s a great poster, it’s simple, not too many words, funny, provocative. So, we had an exhibit at UCLA in the mid ‘90s and there were 4 or 5 high school students standing around this poster saying, “Wow, you’ve got posters up to the minute.” And I went over to them and I said, “Look at the date. This is before you were born.”

Is that one of your goals with the exhibitions? To show the evergreen nature of this work?

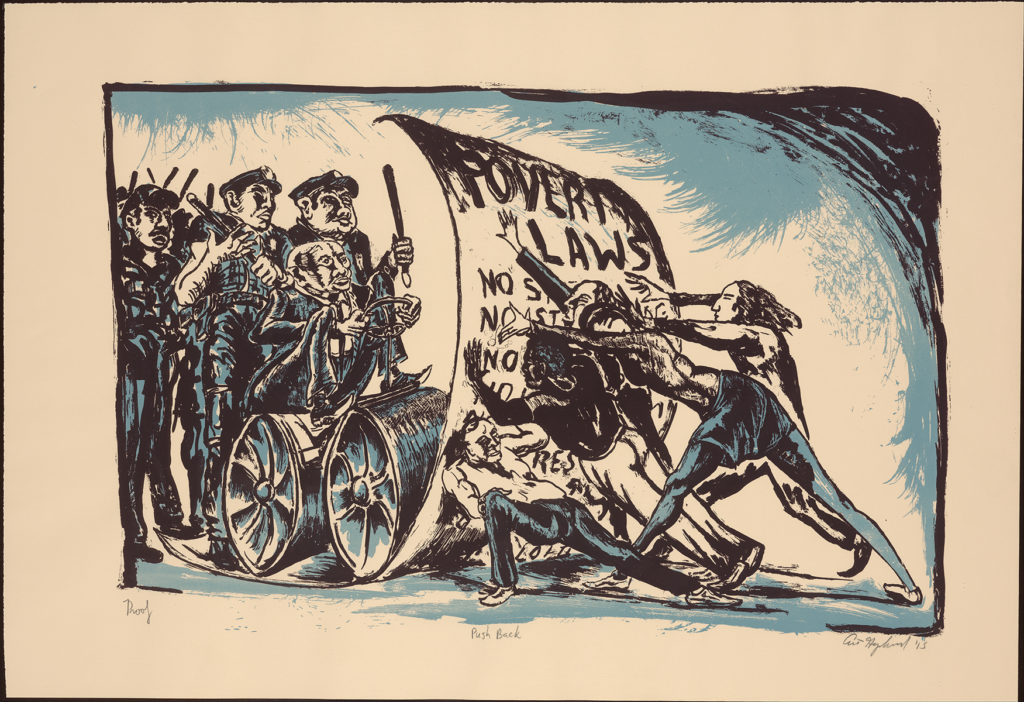

Absolutely. I mean that’s why we did the police abuse exhibition now. It basically goes back five decades. It’s 50 years of posters protesting police abuse. Mainly in the United States, but also internationally.

What’s the goal for CSPG?

Well the aim right now is really to digitize the collection and get it online. We have 10% of the collection digitized. But the mission is to collect and to document, because stories get lost. All the exhibitions, they’re showing massacres, they’re showing genocide, they’re showing police abuse, they’re showing all of these horrible things. And people often ask me, “How can you look at this stuff all day long?” I said, “Because the poster artists are optimists. They believe people can change if they have the information.”

Yes, that’s the reason why they’re doing it, right?

That’s why they’re doing it, and that’s why I’m doing this, because I believe that people can change if they knew the truth.

“Push Back” by Art Hazelwood, 2015. The poster is part of the CSPG exhibit “To Protect & Serve? Five Decades of Posters Protesting Police Violence.”

And what happens 20, 50 years from now?

Well, my goal is to stay independent, because the other option is to become part of the university. Universities, for all the fabulous things that they do, they also censor. We did an exhibition at USC in 1992 on the 500 years since Columbus, and how the legacy of racism and exploitation and genocide continues. And one of the board of trustees was Italian and took [the exhibit] as an affront to Columbus. It really wasn’t about Columbus, it was about colonialism. And he ordered it down.

Do you have a favorite poster?

I’m always amazed at the creativity and vision of artists. Every week I’ll say, “Oh my God, how do they think of that?” But it’s always still going to be the poster I saw that kid trying to figure out. It has to be my favorite one because that one changed my life.

What makes a perfect poster?

The right balance between aesthetics and message. If you only rely on the corporate press, the New York Times and L.A. Times, for your information, you’re not going to get the side from the street, from the movement, from the activists. The posters are primary historical documents that are recording the issues that were at the time, and the passions that were at the time, and the divisions that were at the time. You’re not going to get it anyplace else.

Copyright Capital & Main

-

Latest NewsApril 10, 2024

Latest NewsApril 10, 2024The Transatlantic Battle to Stop Methane Gas Exports From South Texas

-

Latest NewsApril 23, 2024

Latest NewsApril 23, 2024A Whole-Person Approach to Combating Homelessness

-

Latest NewsMarch 27, 2024

Latest NewsMarch 27, 2024Street Artists Say Graffiti on Abandoned L.A. High-Rises Is Disruptive, Divisive Art

-

State of InequalityApril 11, 2024

State of InequalityApril 11, 2024Dispelling the Stereotypes About California’s Low-Wage Workers

-

Latest NewsApril 24, 2024

Latest NewsApril 24, 2024An Author Reflects on the Effort to Rebuild L.A. After the ‘Violent Spring’ of 1992

-

State of InequalityMarch 28, 2024

State of InequalityMarch 28, 2024Los Angeles Hotel Workers Could Use the 2028 Olympics to Their Advantage

-

Striking BackApril 12, 2024

Striking BackApril 12, 2024Organizing the Slopes

-

State of InequalityApril 25, 2024

State of InequalityApril 25, 2024California Often Leads Change, but Not for Single-Payer Health Care