Labor & Economy

The Business of Change: One Private-Equity Pioneer Is So Fed Up With the Industry, He’s Ready to Quit

Co-published by Fast Company

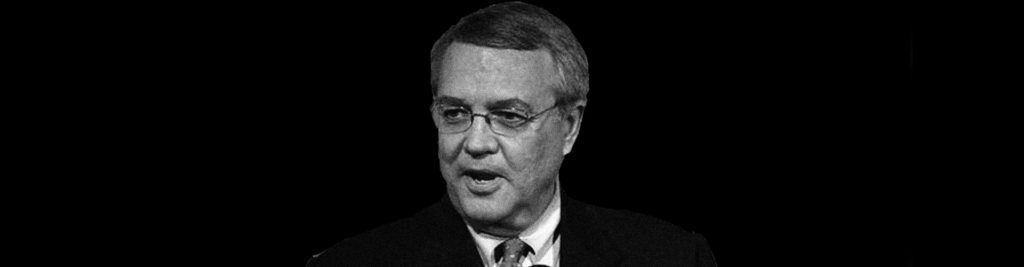

Leo Hindery has long been outspoken about super-rich fund managers who exploit a loophole that allows them to pay the capital-gains tax rate—about half the ordinary tax rate—on a huge chunk of their personal income.

For Leo Hindery, the declining standards in private equity are part of a larger picture in which the leaders of corporate America are focused on short-term profits at the expense of the greater good to society.

Co-published by Fast Company

“Greed is winning,” Leo Hindery tells me on the latest episode of my podcast, The Bottom Line. “I don’t like its trends. ” Hindery, a private-equity pioneer, is fed up with the mores of his $2.5 trillion industry.

“I’m not sure I’m going to stay in the business,” he says.

See Other Stories in This Series

Hindery, who runs New York-based InterMedia Partners, stresses that he looks forward to continuing to make “thoughtful investments” on behalf of others. But he is mulling a new vehicle outside the realm of private equity.

“I don’t like the fee structure,” he explains. “I think it’s usurious. I think it’s caused really unfortunate—almost unethical—behaviors by some of the managers. I’m not happy with it. So we’re going to change our own perspectives.”

Hindery’s displeasure comes in large measure from seeing private equity change over time. When the field began to take off in the mid-1980s, he says, there was more of an inclination to acquire businesses and hold onto them for five to seven years, building them up along the way.

But now, he says, there is so much capital chasing so few good deals, it has put pressure on private-equity managers—often young generalists with zero experience in the types of businesses that they’re buying—to become overleveraged and then try to turn a relatively quick profit.

“They’ve backed away from the longer hold, and they’ve gone for the more expedient action of cutting . . . costs, especially employee costs,” Hindery says.

His peers infuriate him in other ways, as well. Hindery has long been outspoken about super-rich fund managers who exploit a loophole that allows them to pay the capital-gains tax rate—about half the ordinary tax rate—on a huge chunk of their personal income. “It’s just unconscionable,” Hindery says. “It’s beyond intellectually absurd.”

“There’s nothing that suggests that what we do as managers of these monies is a capital gain,” he adds. “To call it a capital gain is to call an orange an apple.”

For Hindery, the declining standards in private equity are one piece of a larger picture in which the leaders of corporate America have become increasingly focused on short-term profits at the expense of the greater good to society.

When Hindery went to work for natural resources giant Utah International in the early 1970s, fresh out of business school at Stanford, he says he plunged into a world in which major CEOs “were patriots.”

“They believed in the value of their employees as assets,” he says. “They believed in their responsibility to their communities and to their nation.” Today, however, “I can’t make that generalization much anymore.”

Hindery acknowledges that social impact investing is a force to be reckoned with, as more and more public-pension funds, university endowments and charitable foundations steer their investment dollars into those companies that are good stewards of the environment and their workers.

But money managers and top corporate executives—the bulk of whose own compensation is typically linked to their company’s share price—are still often motivated by other concerns. At least for now, says Hindery, “greed is winning.”

You can listen to my entire interview with Hindery here, along with Larry Buhl reporting on efforts by a group of wealthy individuals called the Patriotic Millionaires to battle income inequality, and Rachel Schneider exploring why we need to develop new indicators that measure people’s overall financial health, not just their creditworthiness.

The Bottom Line is a production of Capital & Main.

-

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 29, 2026

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 29, 2026Are California’s Billionaires Crying Wolf?

-

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026Amid the Violent Minnesota Raids, ICE Arrests Over 100 Refugees, Ships Many to Texas

-

Dirty MoneyJanuary 30, 2026

Dirty MoneyJanuary 30, 2026Amid Climate Crisis, Insurers’ Increased Use of AI Raises Concern For Policyholders

-

Featured VideoFebruary 4, 2026

Featured VideoFebruary 4, 2026Protesters Turn to Economic Disruption to Fight ICE

-

The SlickFebruary 2, 2026

The SlickFebruary 2, 2026Colorado May Ask Big Oil to Leave Millions of Dollars in the Ground

-

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 5, 2026

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 5, 2026Lawsuits Push Back on Trump’s Attack on Child Care

-

Column - California UncoveredFebruary 6, 2026

Column - California UncoveredFebruary 6, 2026What It’s Like On the Front Line as Health Care Cuts Start to Hit

-

The SlickFebruary 10, 2026

The SlickFebruary 10, 2026New Mexico Again Debates Greenhouse Gas Reductions as Snow Melts