Former colleagues hope that the organizer and activist’s outsized legacy can endure.

The civil rights leader showed that even in Los Angeles, color drives class divisions and racial justice drives economic justice.

The civil rights movement’s leading disciple of nonviolent protest reflects on the life and work of the late congressman.

Here at the end of President Obama’s final term in office, we seem to be having the national conversation about race that he called for at the beginning of his candidacy in 2008.

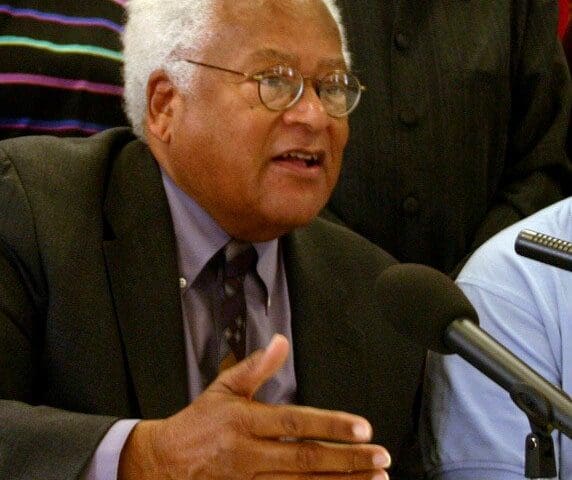

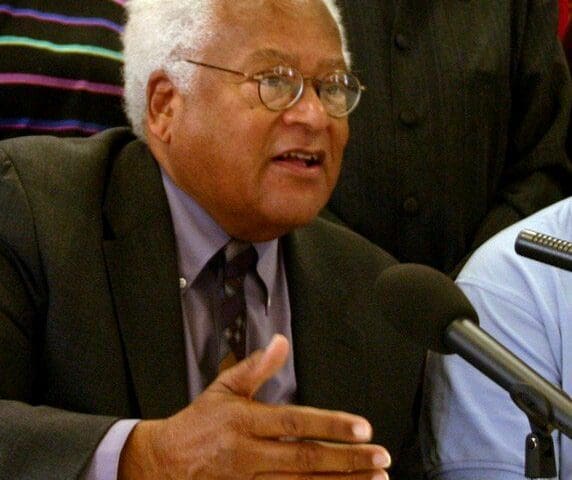

At age 88, civil rights leader, organizer and thinker Reverend James Lawson Jr. is still busy teaching all who will hear that nonviolence “represents a new day for activism.”

Civil rights leader Reverend James Lawson announced last Saturday that he’s planning to give himself to a new nonviolent direct action campaign with the Children’s Defense Fund, but wasn’t ready yet to discuss the details. The setting was his monthly workshop on the theory of nonviolence, where upwards of 35 people of diverse ages and backgrounds were gathered to hear Lawson present his provocative thoughts on basic human values, spirituality and the need for systemic social change.

Credited with introducing nonviolent direct action to the 1960s civil rights movement, Rev. Lawson feels the theory of nonviolence has had the equivalent impact on our understanding of the universe as Einstein’s theory of relativity. He sees the recent growth of California’s labor movement as an outgrowth of what Lawson calls “this science of social change” introduced to the state by farm worker leader Cesar Chavez in the 1960s and 70s.

Lawson was dressed last weekend in pressed khaki slacks,

» Read more about: James Lawson: Training for Nonviolence’s Next Step »

I have been wading through the three volumes of Taylor Branch’s history, America in the King Years, and reliving the dozen years between Montgomery and Memphis. The Montgomery bus boycott catapulted Martin Luther King, Jr., into the national headlines; Memphis was where he was assassinated. Throughout that tumultuous time, the Reverend James Lawson stood just offstage, a key partner in the nonviolent campaign for full citizenship for African Americans.

While King spearheaded the campaign to desegregate the buses in Montgomery, Lawson trained students in Nashville in the ways of nonviolence. He led small workshops tucked away in church basements. He taught his students not to react to taunts and threats. He gave them tools to remain calm and centered while undergoing arrest or physical attacks. Lawson believed that only by enduring the blows of hatred could haters see their own humanity. He brought Gandhi’s understanding of nonviolence to this country and he trained thousands of civil rights workers during those years.