As with many states in the country, North Carolina’s historically low unemployment rate – 3.7 percent in December – conceals trouble: persistent racial disparities, the geographic isolation of low income and struggling rural communities, and an affordable housing crisis.

But unlike the rest of the country, North Carolina has also seen a growth in the percentage of people living in or near poverty. The proportion of people living below twice the poverty level – $41,560 for a family of three in 2018 – grew to 33 percent between 2016 and 2018, a 2.6 percentage point increase, according to the D.C.-based Economic Policy Institute. (Nationally, the percentage living below twice the poverty level declined by 0.9 percent during the same period.)

Meanwhile, well-to-do North Carolinians continue to thrive. In 2018, the top 20 percent of households took in more than half of all state income; the bottom 20 percent took in just three percent.

“North Carolina never truly recovered from the Great Recession,” explains Patrick McHugh, an economic analyst with the North Carolina Justice Center. “A smaller share of people are working today than before Wall Street recklessness and greed crashed the economy. Many communities across the state still have fewer jobs, and over 40 percent of North Carolinians don’t earn a decent living wage.”

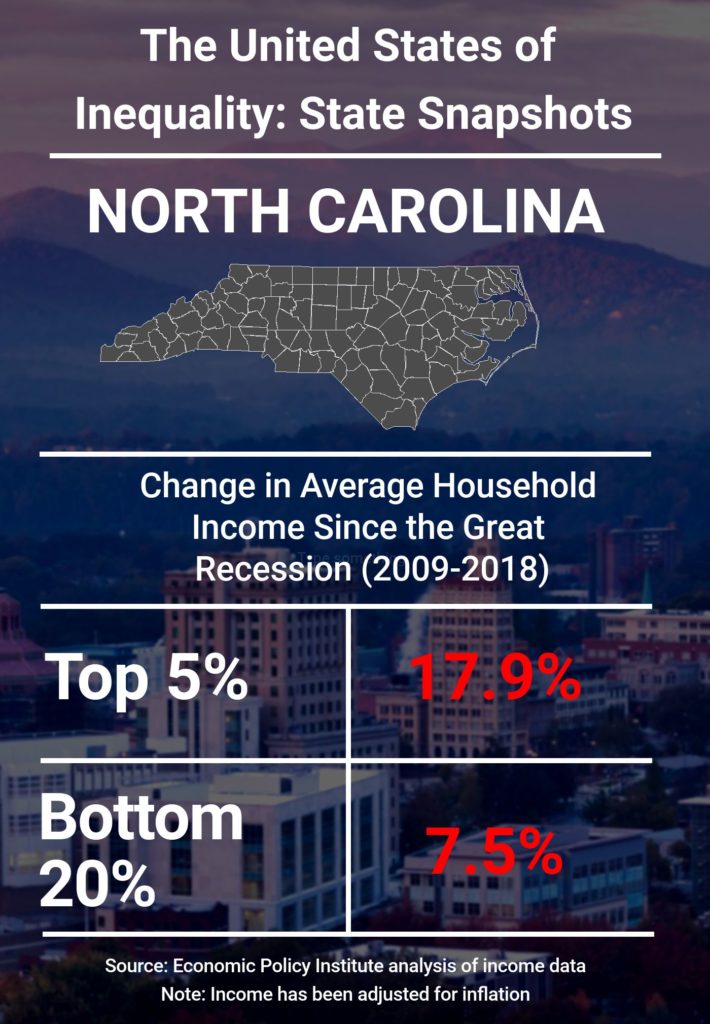

From 2009 to 2018, incomes for the bottom 20 percent of households grew 7.5 percent when accounting for inflation, while those in the top five percent saw their incomes balloon 17.9 percent, at two-and-a-half times the economic benefit flowing to those at the bottom, according to a new analysis from the EPI.

From 2009 to 2018, incomes for the bottom 20 percent of households grew 7.5 percent when accounting for inflation, while those in the top five percent saw their incomes balloon 17.9 percent, at two-and-a-half times the economic benefit flowing to those at the bottom, according to a new analysis from the EPI.

In urban areas, like Charlotte’s home county of Mecklenburg, unemployment is low, but workers face an increasingly expensive housing market. Statewide, a minimum wage worker would need to clock 94 hours per week to afford a two-bedroom rental – and even more hours in Mecklenburg County, according to the National Low Income Housing Coalition. Charlotte, the state’s largest city, was ranked dead last in economic mobility among the 50 largest U.S. cities in 2014.

North Carolina’s racial wage gap is compounded by an unemployment gap and, most distressingly, by an infant mortality gap. African Americans and Latinos in the state are at least twice as likely to be unemployed as whites, and the disparity between black and white long-term unemployment outstrips both the national average and the average for the South Atlantic states. A black baby in Charlotte is nearly five times as likely to die before the age of one as her white counterpart.

Meanwhile, the state’s rural workers have increasingly “been mired in a pattern of stagnant employment or actual loss of jobs,” according to the North Carolina Justice Center’s William Munn. The state’s four main metro regions – Charlotte, Raleigh, Wilmington, and Asheville – appear to be on a different economic trajectory than the 13 more rural parts of the state that have lost jobs since the recession.

And low-income workers are having to travel increasingly greater distances to find employment in North Carolina’s largest cities. Between 2000 and 2012, the number of jobs in or near low-income neighborhoods dropped dramatically, according to the North Carolina Justice Center.

Contributing to these trends is a state legislature that has bound cities by adopting so-called preemption laws, which prevent them from using one of the strongest anti-poverty and anti-inequality tools: raising the minimum wage.

Copyright Capital & Main