Latest News

Presidential White Power

At least a dozen White House figures have ties to racist and anti-immigrant groups. But there’s a long history of this.

White supremacy is as American as the Constitution – and as presidential as the marbled halls of 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue. The White House, constructed with the labor of more than 200 African-American slaves, shows that from the very beginning, the phrase “all men are created equal” applied only to white male citizens. Unfortunately, white supremacy within this building is not only part of its foundation, but of its legacy.

Watch Video —

“The White Nationalist House: Extremism in the Trump Administration”

Most of our “founding” fathers, including our first president, were slave owners. But these important white men were more than mere products of their time. They laid the intellectual groundwork of American white nationalism. For example, Thomas Jefferson, the third U.S. president and the principal author of the Declaration of Independence, also authored white supremacist theories. Jefferson, in his only published full-length book, Notes on the State of Virginia, wrote: “The improvement of the blacks in body and mind, in the first instance of their mixture with the whites, has been observed by everyone, and proves that their inferiority is not the effect merely of their condition of life.” Jefferson also pushed Congress to pass the Act Prohibiting Importation of Slaves in 1808, ending the international slave trade — while legalizing domestic slave commerce.

“This is a country for white men, and by God, as long as I am president, it shall be a government for white men.”

— President Andrew Johnson

In 1830, the seventh president of the United States, Andrew Jackson, signed the Indian Removal Act. Jackson, who owned more than a hundred slaves, also felt that Native Americans were inferior to white men. Nearly 50,000 Native Americans were forcibly removed from their land via the law. He said: “Established in the midst of another and a superior race, and without appreciating the causes of their inferiority or seeking to control them, they must necessarily yield to the force of circumstances and ere long disappear.” The Indian Removal Act further solidified the cotton and slave industry in the South by opening up millions of acres of land to white settlers. More than 15,000 Native Americas died in the removals.

The American Civil War catapulted the nation into direct conflict with some of these founding principles and early statutes by eradicating slavery. These advances were stopped immediately after the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln; his successor, President Andrew Johnson, wrote: “This is a country for white men, and by God, as long as I am president, it shall be a government for white men.” Johnson returned seized Confederate land to its rebel owners.

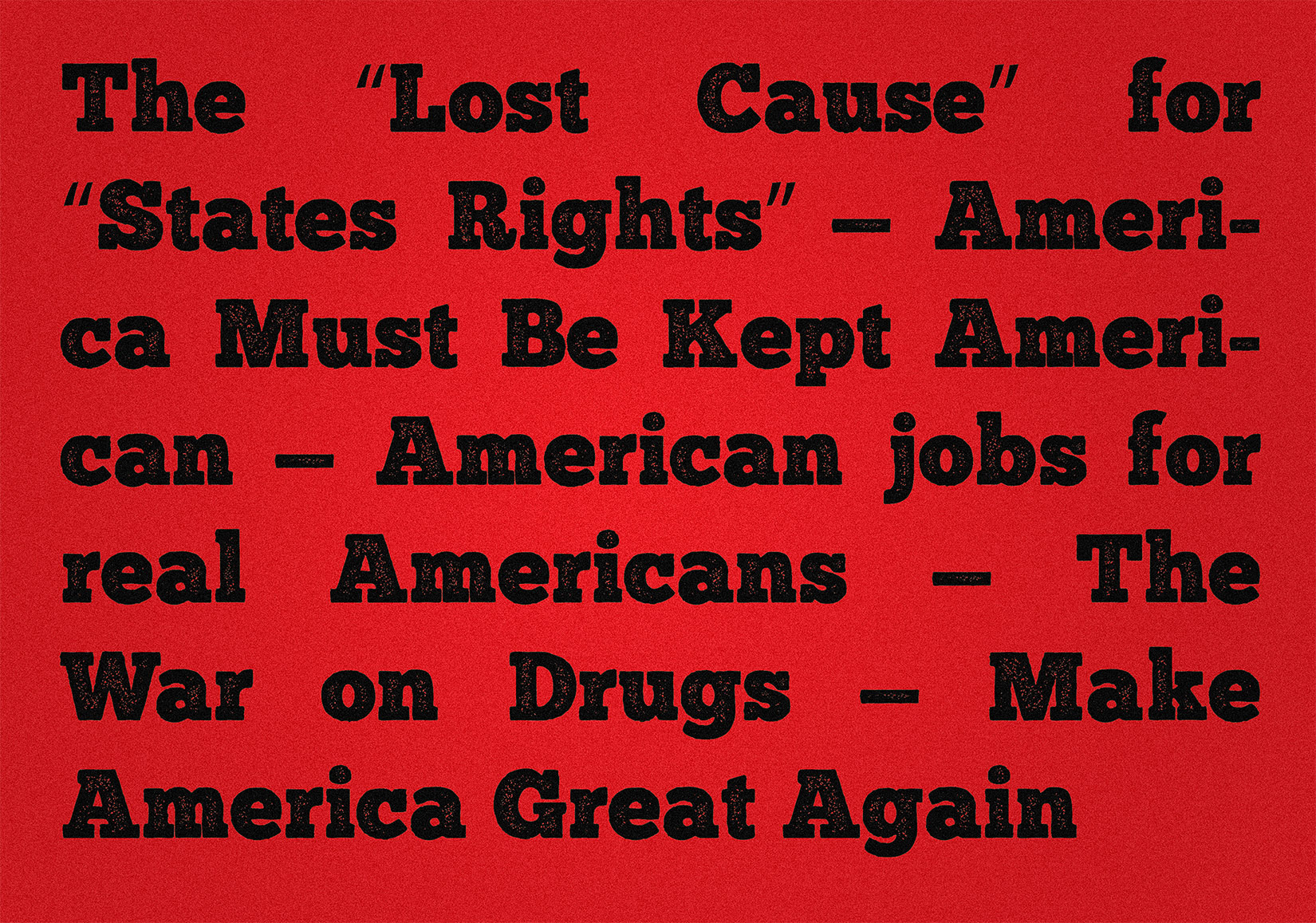

A half century later, President Woodrow Wilson hosted a screening of Birth of a Nation in the White House. The film is a cinematic adaptation of The Clansman, the second novel of a trilogy that depicts Ku Klux Klan members as romantic heroes who save the nation from freed African slaves and the chaos they unleash upon their former masters. The film and the book promoted the “Lost Cause” movement, whose pseudo-historical ideology claimed that the Civil War was not primarily about slavery and its abolition but was about Southern “states’ rights.”

Herbert Hoover supported and encouraged the illegal deportations of Mexicans and Mexican-Americans. His administration used the slogan,

“American jobs for real Americans.”

The film and the trilogy inspired the revival of the Klan months after the screening. But Wilson’s embrace of the film was not the only sign that his administration believed and supported white supremacy. Wilson’s Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels was an outspoken white supremacist and segregationist. Daniels was known as one of the perpetrators of the Wilmington massacre of 1898, a white race riot in Wilmington, North Carolina, in which 2,000 armed white men killed at least 60 African-Americans.

* * *

After World War I, white supremacists within the federal government turned their attention to immigration. President Calvin Coolidge signed the Immigration Act of 1924, legislation co-authored by Congressman Albert Johnson, a eugenicist who opposed interracial marriage and immigration. The bill was inspired by eugenics race theories that heavily favored migration from the “racially superior” Northern European countries. In his first address to Congress, President Coolidge said: “America must be kept American.”

The Great Depression would offer yet another opportunity to mix white supremacist thought and immigration policy. Due to soaring unemployment rates throughout the country, Mexicans and Mexican-Americans were targeted and blamed for the economic crisis. In 1929, President Herbert Hoover’s administration helped forcibly repatriate as many as 1.8 million Mexican and Mexican-Americans to Mexico; about 60 percent were American citizens.

Although most of the “repatriation drives” were executed by local and state officials, President Hoover supported and encouraged them. “American jobs for real Americans” was his administration’s slogan to justify these illegal deportations. Hoover’s Secretary of Labor, William N. Doak, said, “My conviction is that by strict limitation and a wise selection of immigration, we can make America stronger in every way, hastening the day when our population shall be more homogeneous.”

In 1953, Dwight Eisenhower launched “Operation Wetback,” a military-style deportation campaign aimed at Mexicans and Mexican-Americans.

On February 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, allowing the U.S. government to forcibly relocate and incarcerate more than 117,000 Japanese and Japanese-Americans in concentration camps after Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor. The executive order was challenged as unconstitutional in the U.S. Supreme Court, but it was ultimately upheld. Associate Justice Hugo Black wrote the majority opinion in favor of supporting the order. Black, a Roosevelt appointee, had belonged to the Ku Klux Klan before his political and legal career. Dissenting Associate Justice Frank Murphy wrote that the executive order “falls into the ugly abyss of racism” and represented the “legalization of racism.” The concentration camps remained in operation until 1946.

* * *

Even after some historic victories against Jim Crow laws, President Dwight Eisenhower refused to endorse Brown v. Board of Education. Eisenhower allegedly told Supreme Court Chief Justice Earl Warren that white Southerners “are not bad people” and that they were concerned that “their sweet little girls [are not] required to sit in school alongside some big black buck.” Eisenhower’s public protest only continued to delay the court-mandated desegregation of schools. But this was not the only example of Eisenhower’s administration showing its sympathy for white supremacist ideas. In 1953, Eisenhower launched “Operation Wetback,” a military-style deportation campaign aimed at Mexicans and Mexican-Americans. The U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service reported that 1.1 million people had been deported or removed under the operation.

In 1964, Lyndon Johnson’s signing of the historic Civil Rights Act challenged decades of white supremacy; unfortunately, we now know that many of LBJ’s private and off-the-record conversations were laced with racial slurs to describe African-Americans. Almost at the same time, Johnson’s administration ordered the FBI to run surveillance of African-American civil rights leaders and organizations. LBJ’s administration saw the expansion of programs like COINTELPRO (created in 1956 to track the Communist Party’s activities), whose attention was shifted almost entirely to the Black freedom movement. Johnson’s support for then-FBI director J. Edgar Hoover’s efforts to “disrupt, misdirect, discredit, or otherwise neutralize” these individuals and organizations are historically unquestionable. Hoover and his COINTELPRO program continued to wreak havoc on African-American, Indigenous, Puerto Rican and Mexican-American communities during the Johnson and Nixon administrations.

Donald Trump’s administration seems to be resurrecting the long historical line of blatant,

unabashed support for white supremacy.

As the United States drew closer to the 21st century, White House support for white supremacy was muted into racially coded policies, including presidents Nixon’s and Reagan’s “War on Drugs.” These policies led to generations of mass incarceration and racial stereotyping that are still affecting communities today. Recently rediscovered taped conversations between then-California Gov. Reagan and President Nixon captured Reagan musing, “To see those, those monkeys from those African countries—damn them, they’re still uncomfortable wearing shoes!”

Today, President Donald Trump’s administration seems to be resurrecting the long historical line of blatant, unabashed support for white supremacy. From the day of its launch in 2015, Trump’s first presidential campaign reverberated with the wailing of anti-immigrant xenophobia. “They’re bringing drugs,” he said of Mexican immigrants. “They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists.” Trump’s then-chief strategist was Steve Bannon, the executive chairman of Breitbart News, the self-proclaimed “platform for the alt-right” – a term created by white nationalist Richard Spencer to describe a far-right movement centered on white nationalism. Although President-elect Donald Trump would disavow the alt-right movement and Bannon denied being a white nationalist, the stage was set for the Trump administration’s acceptance of white supremacy and white supremacists.

* * *

Capital & Main has found that at least 12 current and past vital officials and staffers within the Trump administration have ties to neo-Nazi, anti-Muslim and anti-immigrant nativist hate groups. Stephen Miller, President Trump’s senior policy adviser, is deeply connected with a known hate group, the Federation for American Immigration Reform (FAIR). He was the principal architect of Executive Order 13769, otherwise known as the Muslim Ban, and the Trump administration’s family separation policy. In September 2019, hundreds of Miller’s private emails were leaked to the Southern Poverty Law Center, a nonprofit organization known for its identification of hate groups and other extremist organizations.

The emails were direct communications with Breitbart News editors from March 2015 through June 2016, with the majority exchanged before Miller joined the Trump campaign team. The emails show a pattern of sympathy for white nationalism and anti-foreigner conspiracy theories — all while referencing a “white genocide”-themed novel called The Camp of the Saints. The book was written in 1973 and is considered a racist, xenophobic and anti-immigrant classic. The Camp of the Saints is a favorite among white nationalist websites like VDare and the American Renaissance. The French novel depicts the end of modern Western civilization due to immigration. The book was promoted by Steve Bannon, Republican Congressman Steve King, France’s National Rally leader Marine Le Pen and by Special Assistant to President Trump Julia Hahn.

When COVID-19 began to rage through the United States, its citizens looked to the administration for hope and unity. Instead, they found xenophobic policies and statements by the president and his staff. As the virus took hold, President Trump intentionally coined the term “Chinese Virus”; not soon after, harassment and crimes targeting Asian-Americans began to rise. The organization Stop AAPI Hate Reporting Center recently released a report documenting more than 800 incidents of discrimination and harassment in the last three months in California against Asian-Americans. But instead of apologizing and changing course, the president doubled down. At his highly criticized campaign rally in Tulsa, the president called the coronavirus the “Kung Flu.” And during the first night of the 2020 Republican National Convention, Trump said, “We are doing an incredible job on the China virus!”

The president’s words recall the xenophobic environment created by another president, Chester A. Arthur, who signed, in 1882, the infamous “Chinese Exclusion Act,” which stopped Chinese workers from migrating to the United States. On the policy level, instead of confronting the COVID-19 crisis head on, the Trump administration tried to use the coronavirus to further its restrictive immigration agenda. In April, the president vowed to halt all immigration to the United States. The executive order eventually fell short of that pledge but it continues to be updated, with more restrictions being added.

Today the United States is the epicenter of the global pandemic, while racial inequalities have made themselves very apparent – we see that Black and Latino Americans are affected by COVID-19 at disproportionately higher rates than whites. But we have also witnessed a reckoning against the inequalities that the virus has exposed, from mass marches to end the police killing of Black people to the toppling of Confederate and other historical statues that represent white supremacy. History reveals that white supremacy in America is older than the White House, but current events show that many Americans, especially the young, seem ready to fight it.

Copyright 2020 Capital & Main

-

The SlickFebruary 10, 2026

The SlickFebruary 10, 2026New Mexico Again Debates Greenhouse Gas Reductions as Snow Melts

-

Latest NewsFebruary 12, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 12, 2026Trump Administration ‘Wanted to Use Us as a Trophy,’ Says School Board Member Arrested Over Church Protest

-

Latest NewsFebruary 10, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 10, 2026Louisiana Bets Big on ‘Blue Ammonia.’ Communities Along Cancer Alley Brace for the Cost.

-

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 12, 2026

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 12, 2026They’re Organizing to Stop the Next Assault on Immigrant Families

-

The SlickFebruary 16, 2026

The SlickFebruary 16, 2026Pennsylvania Spent Big on a ‘Petrochemical Renaissance.’ It Never Arrived.

-

The SlickFebruary 17, 2026

The SlickFebruary 17, 2026More Lost ‘Horizons’: How New Mexico’s Climate Plan Flamed Out Again

-

Latest NewsFebruary 18, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 18, 2026Effort to Fast-Track Semiconductor Manufacturing Faces Community Pushback

-

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 19, 2026

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 19, 2026Cuts Aimed at Abortion Are Hitting Basic Care