The National Employment Law Project’s Michele Evermore makes it her business to understand the nation’s unemployment system, a bureaucracy that receives attention only during recessions like the one we are now experiencing.

Last summer, when she contemplated the possibility of another economic crash, she didn’t think the rickety state-run programs could handle one.

Then came COVID and a tsunami of claims, which crested in late March, when 6.8 million people applied for unemployment insurance in one week. (Prior to that, the largest number of claims filed in one week was 695,000, in 1982).

In some ways she was right. State unemployment offices buckled from the pressure of millions suddenly needing assistance. The crisis had hit at a moment when agencies intentionally made their application processes more onerous, according to Evermore.

States emerged from the Great Recession with depleted unemployment trust funds and no appetite for taxing employers in order to restore their fiscal health.

That’s because states emerged from the Great Recession with depleted unemployment trust funds and no appetite for taxing employers in order to restore their fiscal health. So states have tried to keep the unemployed from entering the system. “They made the systems less penetrable. They made the questions harder. They made the computer systems more restricted,” says Evermore.

But if the massive surge in claims revealed the system’s flaws, Congress’ rapid and uncharacteristically generous response to the pandemic – $600 a week in supplemental unemployment benefits – also underscored the benefits of unemployment insurance to an economy in freefall.

The most urgent – and overdue – question facing federal lawmakers in the coming weeks is the fate of as many as 30 million workers, many of whom saw their expanded benefits expire last week.

The administration and Senate Republicans have put forward a plan to reduce weekly benefits by $400 until states can update their systems to allow them to pay the unemployed 70 percent of their income before they lost their jobs. Democrats would like to restore the $600 weekly benefit and avoid burdening state systems with new, difficult-to-administer funding formulas.

The standoff has left Florida resident – and out-of-work cruise line singer – Eileen Lymus-Sanders in a state of high anxiety. Her savings are depleted, and she is attempting to defer payments on bills. “A lot of my bills are two or three months behind,” she says. “It’s very stressful.” Now she is living off just $125 per week in benefits.

“It’s not a matter of me not wanting to go back to work. It’s a matter of there being no work to go back to,” says Lymus-Sanders, who is 53 and lives in Clearwater, northwest of Tampa.

She has been unemployed since March, when her industry shut down as COVID cases shot up. A virtue of the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act, passed by Congress in late March, is that it expanded unemployment insurance’s reach to include gig workers like her.

But because of glitches in Florida’s notoriously difficult-to-access unemployment system, she did not receive benefits until mid-May, by which time she had exhausted her savings. Florida, a critical battleground in November, has been subject to widespread criticism for the state’s handling of unemployment claims, as Capital & Main has reported. The state had the slowest rate of processing initial claims of any state in the country during the initial weeks of the outbreak. Donald Trump ally Gov. Ron DeSantis has blamed the failures of the state’s system on his predecessor, fellow Republican Rick Scott, and on claimants themselves.

Still, for a period of time, the weekly lifeline allowed Lymus-Sanders to pay essential bills while deferring others. (This month, she will be able to cover only her mortgage, cell phone bill and car insurance payment).

Spending among unemployment benefit recipients created a needed economic stimulus, according to a study by JP Morgan Chase.

The CARES Act unemployment assistance – which provided a $600 per week boost on top of any state benefit a worker might be eligible for before it expired last week – has helped the unemployed pay for rent, food, medicine and other necessities. It has also propped up the economy overall. Spending among unemployed people created a needed stimulus, according to a July study by JP Morgan Chase.

The pandemic assistance programs also embodied some of the weaknesses of the U.S. unemployment system. Blacks and Latinos are generally less likely to receive unemployment insurance benefits than their white counterparts. That has continued to be the case for CARES Act-authorized assistance, according to congressional testimony by William Spriggs, chief economist at the AFL-CIO.

“Their plight from the loss of income is compounded because of their low levels of wealth and specifically their low levels of liquid wealth,” he wrote.

But what bothers Republicans – including the president – is that the $600 in weekly pandemic assistance is more than what most unemployed workers earned at their last jobs.

“We had something where it gave you a disincentive to work last time… We want to create a very great incentive to work,” Trump told a Fox Business interviewer.

There is no evidence that the pandemic assistance has contributed to job losses or impeded the economic recovery.

There is no evidence that the pandemic assistance has contributed to job losses or impeded the economic recovery. But it is true that, unlike Lymus-Sanders, a majority – or 68 percent of unemployed people – are bringing in more from unemployment insurance than they did in weekly earnings from their last job, according to an analysis from the Becker Friedman Institute at the University of Chicago.

Evermore says the large number of workers whose pandemic unemployment insurance exceeds their prior earnings points to how hard low wage workers have been hit by the COVID recession. “So what if they get a little bit more right now! These are people who have struggled mightily for years, and so for a few months of their life, they get a little bit more money on unemployment than they would have gotten on their jobs,” she says.

But the concern that the now-expiring unemployment benefits were too high has put some more conservative Democrats in a difficult spot, according to Lindsay Owens, a fellow at the Roosevelt Institute who formerly served as a top adviser to Sen. Elizabeth Warren. Owens – along with her Roosevelt Institute colleague Bharat Ramamurti – are pushing a Fair Wage Guarantee that would allow the $600 unemployment benefit to be used as a wage subsidy for employees heading back to work. This subsidy would then be phased out as the unemployment level fell.

“The fair wage guarantee would raise wages for millions of formerly low-wage workers as they come off unemployment, which produces big long-term gains for them and for our economy,” they wrote in an op-ed published in the New York Times.

Owens said that the guarantee had received support from progressive Democrats concerned about low wages, as well as from more conservative members of the Democratic caucus who are vulnerable to the argument that the pandemic unemployment insurance has created a disincentive to return to work.

By one estimate, one in eight workers have experienced pay cuts during this recession.

Slow wage growth “really inhibited the recovery” from the Great Recession, Owens said in an interview. Higher wages, she explained, would have led consumers to spend more, creating benefits for the economy overall. By one estimate, one in eight workers have experienced pay cuts during this recession.

What Owens is proposing is a tool that Democrats could use in negotiation as Republicans seek to slash benefits during a time of sky-high unemployment.

A more comprehensive overhaul of this 85-year-old unemployment insurance program is also in order, according to Evermore. Her wish list includes making gig workers permanently eligible for unemployment insurance, automatically extending unemployment insurance during recessions to avoid the fights like this one, and making part time unemployment insurance available to workers in every state.

And now is the time, says Evermore. “The only time you can get improvements to unemployment insurance is during a recession. Otherwise people just don’t pay attention. It’s not that exciting a topic.”

Lymus- Sanders, meanwhile, longs to get back to cheering audiences, “being on stage with friends,” and even 17-second costume changes. She agrees that the U.S. system could use a makeover. As a cruise line performer, she is in touch with entertainers from countries across the globe with better functioning systems than what is available to her. “A lot of my friends are in other countries, and they are not stressing like we are,” she says.

Copyright 2020 Capital & Main

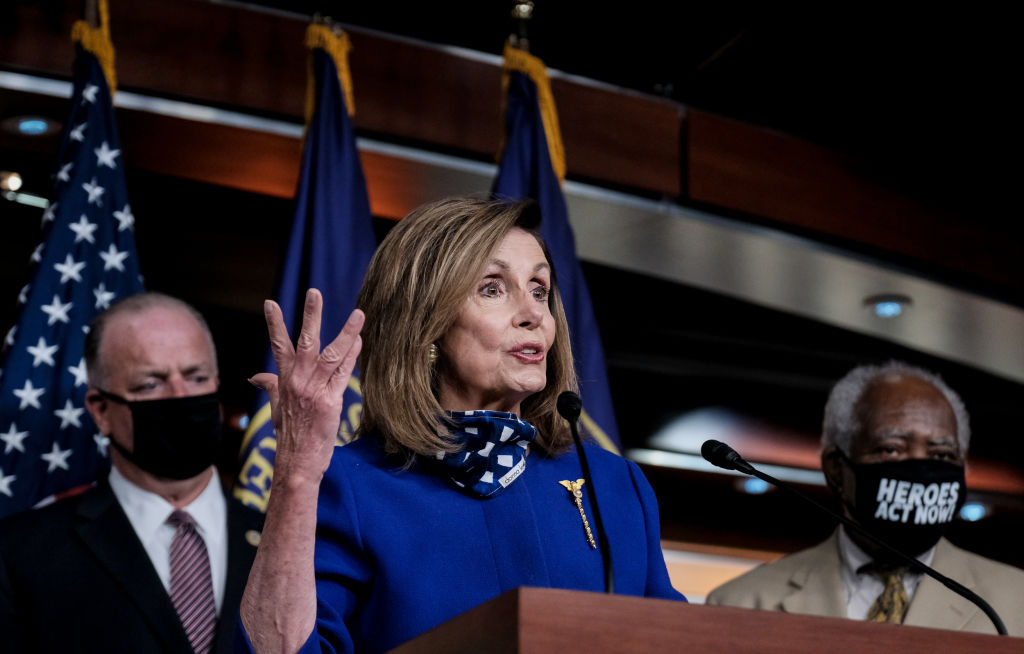

Photo: Nancy Pelosi speaks during a July 24 news conference in Washington, DC, urging the extension of supplemental unemployment benefits. (Michael A. McCoy/Getty Images)