The Slick

New Mexico’s Gas and Oil Industry Decries Pause on U.S. Drill Leases

But not everyone in the state is rankled by Joe Biden’s executive order.

Last week, with the stroke of a pen, President Joe Biden enacted an indefinite halt to oil and gas leases on federal land across the country. The executive order reflects a broad set of climate change goals the administration has been working on since well before the election. Among the many provisions – including creating a National Climate Task Force and two environmental justice councils and building climate considerations into foreign policy and national security – the order calls for a review of current leasing and permitting practices on federal lands.

“We’re going to review and reset the oil and gas leasing program,” Biden said at the signing ceremony. And he clarified, “We’re not going to ban fracking.”

Industry voices say the new federal ban will crater New Mexico’s economy, drive oil and gas operators out of the state and lead to the loss of more than 60,000 jobs by the end of 2022.

Industry message makers – including those in New Mexico – have decried the move, which affects thousands of acres of federal lands in the state. Half of the state’s current petroleum production comes from federal lands, and taxes on lease sales and oil and gas sales buoy the economy.

Those industry voices say the ban will crater the economy, drive oil and gas operators out of the state and lead to the loss of more than 60,000 jobs by the end of 2022. The Independent Petroleum Association of New Mexico (IPANM) calls it “the equivalent of dropping a bomb on operations.”

The New Mexico Oil and Gas Association (NMOGA) has already started a letter-writing and phone campaign to sway the state’s politicians away from backing the act. The Western Energy Alliance, an oil and gas advocacy group, filed suit in U.S. District Court in Wyoming within hours of the order’s signing.

“New Mexicans lose and foreign imports win,” says NMOGA president Ryan Flynn in a written statement.

“The Biden administration has just empowered countries most hostile to the United States,” declares Jim Winchester, IPANM’s executive director, in a statement.

However, outside the industry, very few agree with the end-time rhetoric.

Erik Schlenker Goodrich, executive director of the Western Environmental Law Center, calls the industry claims “frankly bogus.”

He points out that industry has stockpiled thousands of oil and gas leases and drilling permits already, which means production will continue on millions of acres across New Mexico.

Gov. Lujan Grisham has to thread a political needle as it commits the state to lower greenhouse gas emissions while relying on oil and gas revenues to fund more than a third of the state budget.

Janie Chermak, graduate director and professor of economics at the University of New Mexico, says, “It’s not without concern, but the sky is not falling today, I don’t think.”

Meanwhile, New Mexico Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham is taking a wait-and-see approach. States can ask the federal government for an exemption to the pause, but Lujan Grisham hasn’t said what she plans to do. “Our administration is reviewing these orders to evaluate the scope of the impact they will have on our state,” according to a statement her office released in response to Biden’s executive order.

On the legislative side, Dawn Iglesias, chief economist to the New Mexico Legislative Finance Committee, says, “We’ll be working on this over the next few weeks” to try and estimate future impacts, if any.

The oil and gas industry is responsible for just over half of the state’s greenhouse gas emissions, which contribute to the state’s continuing climate crisis.

The Lujan Grisham administration has to thread a political needle as it commits the state to a dramatic shift toward green energy and lower greenhouse gas emissions while relying on oil and gas revenues to fund more than a third of the state budget. A dip in those revenues at the beginning of the COVID-19 crisis last year threw state government into turmoil and prompted a special session of the Legislature.

Economists have warned for years that lawmakers need to diversify New Mexico’s economy so fluctuations in the industry don’t have dire effects on state operations.

One of her first actions after taking office was issuing an executive order that created a climate change taskforce, required state agencies to evaluate the effects of climate change on their operations and called for a framework to reduce emissions from oil and gas operations, among many other goals.

But at the same time, she has worked with other regional governments in support of a proposed natural gas export terminal in Baja California, Mexico, that would take New Mexican gas to Asia.

The state’s overreliance on oil and gas revenues isn’t new. And economists have warned for years that lawmakers need to diversify the state’s economy so fluctuations in the industry don’t have such dire effects on state operations. In fact, the federal ban could offer the state an opportunity rather than the crisis industry spokespeople claim.

“They have so many things on their plate right now,” Chermak says of the Legislature and the governor’s lukewarm response, “but this is probably a good time to say, ‘If we have a window of opportunity, how do we transition out of it?’”

In her statement, Lujan Grisham says that she will work with the Biden administration to create a long-term energy and environment plan “that, crucially, takes into account the individual circumstances and near-term financial reality of states like ours.”

Meanwhile, the reality for some large oil companies seems to be fairly sanguine. David Hager, executive chairman of Devon Energy, one of the biggest producers in the Permian Basin, says that his company has enough permits on hand to keep drilling for another four years. And it is not alone.

* * *

Aside from the technical knowhow and equipment, drilling on federal lands requires two things: a lease for the rights to the oil and gas under a particular patch of land, and a permit to sink a well there to bring the oil and gas up. As Schlenker Goodrich notes, industry has bought and stockpiled thousands of leases and permits across the West in the past couple of years. According to a fact sheet released by the U.S. Department of Interior on the same day as the presidential order, out of 26 million acres leased to the oil and gas industry, 53% are unused and not yet producing oil or gas.

Furthermore, during the Trump administration, the Interior Department offered up more than 25 million acres of land in mineral rights auctions – something the Interior Department itself now calls a “fire sale” – and only 5.6 million acres sold. So the oil and gas industry wasn’t suffering from a lack of land to drill. By all appearances, it wasn’t interested in more.

The industry already faces a tougher future as major economies across the planet transition away from fossil fuels and toward renewable energy sources.

Schlenker Goodrich says the industry suffers from an “ailing business model.” While there may be a lot of oil and gas in the Permian Basin, drilling for it isn’t cheap. And he calls industry’s fight against a pause on federal leases a “deflection away from their own vulnerabilities and their own fragility of the revenue and economic logic that they’re operating under.”

As Chermak explains, production in the Permian – and elsewhere across the country – rocketed up in the 2000s because petroleum prices rose enough to cover the cost of the expensive fracking technology needed to reach deep oil and gas pockets. That led to a cycle of drill-and-debt that left many companies bankrupt.

* * *

In the meantime, oil and gas operations in New Mexico are unlikely to change for the foreseeable future. The pause on new leases does not affect the thousands of leases and permits that have already been issued, and it doesn’t affect leasing and drilling on millions of acres of private and state lands.

Still, when the idea of a license and drilling pause was first floated by the Biden camp last year, Lujan Grisham said that any final action needs to take into account “the individual circumstances and near-term financial reality of states like ours” – which she repeated in her statement on Wednesday.

While the governor remains noncommittal over what action she might take, Schlenker Goodrich is optimistic that the pause in leases – as the Biden administration reviews the federal leasing process – “should give every New Mexican optimism that the federal government is going to play a very constructive role in New Mexico’s future.”

Copyright 2021 Capital & Main

-

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 22, 2026

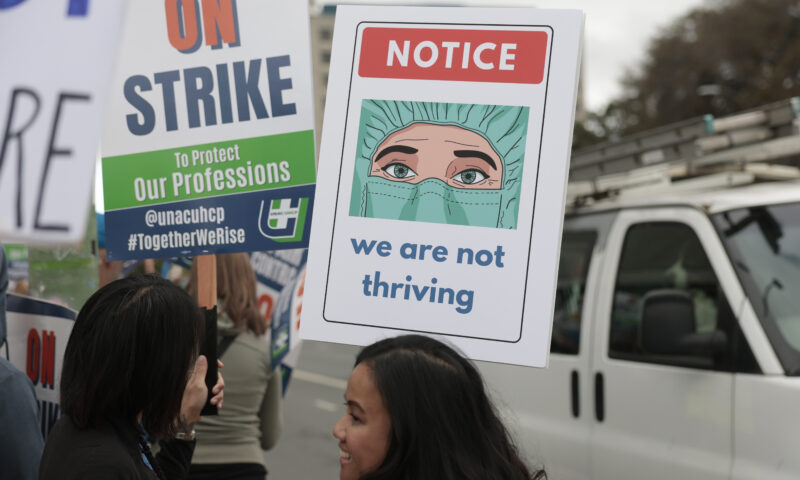

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 22, 2026On Eve of Strike, Kaiser Nurses Sound Alarm on Patient Care

-

The SlickJanuary 20, 2026

The SlickJanuary 20, 2026The Rio Grande Was Once an Inviting River. It’s Now a Militarized Border.

-

Latest NewsJanuary 21, 2026

Latest NewsJanuary 21, 2026Honduran Grandfather Who Died in ICE Custody Told Family He’d Felt Ill For Weeks

-

The SlickJanuary 19, 2026

The SlickJanuary 19, 2026Seven Years on, New Mexico Still Hasn’t Codified Governor’s Climate Goals

-

Latest NewsJanuary 22, 2026

Latest NewsJanuary 22, 2026‘A Fraudulent Scheme’: New Mexico Sues Texas Oil Companies for Walking Away From Their Leaking Wells

-

The SlickJanuary 23, 2026

The SlickJanuary 23, 2026Yes, the Energy Transition Is Coming. But ‘Probably Not’ in Our Lifetime.

-

The SlickJanuary 27, 2026

The SlickJanuary 27, 2026The One Big Beautiful Prediction: The Energy Transition Is Still Alive

-

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 29, 2026

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 29, 2026Are California’s Billionaires Crying Wolf?