Co-published by Newsweek

Editor’s Note: This is the first in a series of United States of Inequality stories to examine the track records of leading presidential candidates on issues affecting income distribution and social mobility.

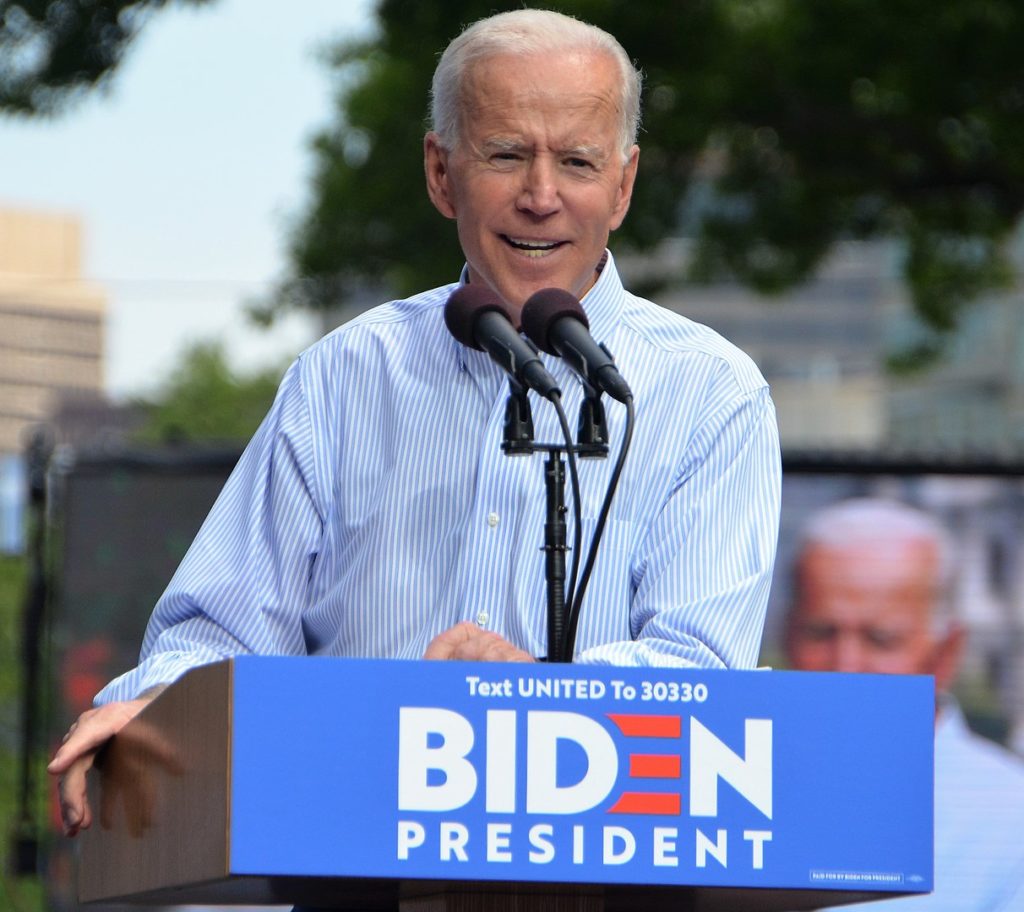

Union support is a bigger prize than ever for Democratic Party presidential candidates in 2020. It comes with cash and ground troops who can connect face to face with voters and get them to the polls on Election Day. A self-proclaimed “union man,” former Vice President Joe Biden has counted on labor throughout his more than 40 years in the U.S. Senate and in the White House.

Biden has consistently voted for minimum-wage increases and in 2007 he cast a vote for the Employee Free Choice Act, which would have allowed workers to unionize if a majority of a company’s employees declared their support for a union by signing cards, instead of being required to hold drawn-out election campaigns.

He’s won an early endorsement from the 300,000-member International Association of Fire Fighters and has long claimed the mantle of “Middle-Class Joe.” But today Biden can’t take labor backing for granted. Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren on Biden’s left, and even Cory Booker, Amy Klobuchar and Pete Buttigieg, in the center, have not only voiced full-throated pro-union stances, they got a jump on Biden by announcing detailed plans to help workers organize unions – thus raising the standard for what it means to be pro-labor.

Last month in downtown Los Angeles, at the “Unions for All Summit” sponsored by the Service Employees International, a sea of SEIU members wearing trademarked purple gear filled the Westin Bonaventure Hotel’s massive San Jose banquet room. From Iowa adjunct professors to New York McDonald’s workers, they described tough living and working conditions, and gave the eight leading Democratic candidates a chance to offer solutions that would help them and their co-workers. (Disclosure: SEIU is a financial supporter of this website.)

Biden was the first to take the stage with his confident, almost cocky grin, lanky frame and thinning silver hair projected close up on monitor screens.

“I am one of those persons who never forgot to say the word ‘union,’” Biden declared.

The first question on stage was a relative softball: How would he help workers organize amid employer opposition? Tseganesh Endegeshet, a recent immigrant from Ethiopia, said she has two jobs to make ends meet and no health insurance. “We haven’t seen your plans yet,” Endegeshet said. “How would you support millions of us to get a union?”

A month after the conference, Biden did get around to unveiling his plan, which includes pledges to ban right-to-work laws, to provide a path for all public-sector employees and domestic and farmworkers to organize, and to repeal a ban on secondary boycotts, which would allow workers to pressure their employers by targeting companies with which the employers do business.

But, before a friendly audience that was hungry for answers, Biden missed the chance to explain how he’d help workers organize amid employer opposition. Biden’s rhetoric was strong, but aside from a promise to raise the minimum wage to $15 per hour, his policy prescriptions were not. Instead, he appeared tone deaf as he asserted that everyone – public and private sector workers alike – “be protected by the NLRB, be part of the entire deal.” The National Labor Relations Board, the federal agency that referees private-sector union elections and bargaining, often gets negative reviews from organized labor in protecting workers’ rights to organize. Biden’s plan now calls for a far tougher NLRB, but he offered the SEIU members no ideas on how he would reform it.

He did, however, announce, “You’re the only ones keeping the barbarians on the other side of the gate and you’ve been getting clobbered.”

But part of the problem Biden may have in lining up labor support is his own coziness with the barbarians – if he defines them as union-busting corporations like Comcast, his fourth-largest donor, whose executives threw a high-dollar fundraiser for him last April and handed over more than $69,000. Or if he was referring to law firms that assist employers with “union avoidance” expertise, like Cozen O’Conner and Ballard Spahr, which have so far raised more than $55,000 and $40,000 for Biden, respectively.

Biden has a solid liberal voting record, but he’s backed policies that have made poor people poorer and more powerless:

- Biden was in the forefront of tough-on-crime policies of the 1980s and ’90s that resulted in epidemic mass incarceration, leaving many of those convicted of nonviolent felonies permanently disenfranchised and unable to support their families. He authored the Violent Crime Control and Enforcement Act of 1994, which allocated $97 billion for new prisons and provided for a federal three-strikes law that helped fill them. Earlier this year, the candidate expressed regret for these law-and-order policies—especially for his role in establishing harsher sentences for crack than for powdered cocaine, penalties that disproportionately punished African-Americans.

- He backed the landmark 1996 Clinton welfare reform bill, the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Act, which trimmed entitlement rolls but increased child-poverty rates. The bill was a key part of the Republicans’ Contract with America, and it has been criticized for pushing welfare recipients into low-wage jobs and fraying the social safety net.

- Biden spearheaded the 2005 Bankruptcy Abuse and Consumer Protection Act, which made declaring bankruptcy cost-prohibitive for the lowest income debtors, leaving many in economic purgatory – unable to pay their debts and rebuild their credit. Banks and credit card companies, like Delaware credit card issuer MBNA, one of Biden’s biggest lifetime financial backers, had clamored for the legislation, arguing that debtors were gaming the system. (MBNA was acquired by Bank of America in 2006). According to University of Pittsburgh economics professor Stefania Albanesi, who studied the bill’s effects, the law offered a solution without a problem. “There was little evidence there was [bankruptcy] abuse,” she said.

President Bill Clinton declined to sign Biden’s bankruptcy bill in 2000, reportedly after then-Harvard Law School professor Elizabeth Warren persuaded Hillary Clinton it was a bad idea. (Later, as a senator, Hillary Clinton would vote for a similar bill in 2001.) Biden never took much heat for the policy. Albanesi pointed out that two years after it was signed into law, the Great Recession hit, and it was therefore hard to assess the results, including the degree to which banks and credit card issuers might have profited, or the extent that consumers were hurt by the bill.

* * *

Biden is now similarly unlikely to face much scrutiny of his past positions – even those that have placed working people in even more precarious economic straits—noted John Logan, a labor historian at San Francisco State University. “I don’t think things like that receive a lot of attention other than to reinforce the brands of the candidates,” he said, meaning to establish whether they are moderate or progressive Democrats. Instead, labor officials are more likely to look at their own relationships with the candidates and at their current stands on issues.

“[Biden] is a regulation Democrat,” said labor historian Nelson Lichtenstein, a professor at the University of California, Santa Barbara, meaning that Biden’s supported AFL-CIO positions while failing to speak up for workers, where doing so might be politically risky.

Biden’s backers, however, point to his support for repealing Citizens United, the landmark Supreme Court case that allows unlimited spending by corporations, unions and other associations on federal elections, and which has come to symbolize the unbridled political power of a tiny economic elite. Moreover, Biden accumulated a progressive record on taxation in the senate, consistently voting for taxes on the very rich, and against eliminating or cutting inheritance taxes. He won a 100 percent score from Citizens for Tax Justice in 2006, and a failing 11 percent “Big Spender” rating from the conservative National Taxpayer’s Union.

And, unlike Lichtenstein, Jared Bernstein, a prominent progressive who served as Biden’s economic adviser during the Obama administration, claims Biden’s commitment to labor runs deep. Bernstein, who now informally advises candidate Biden, places him squarely in the camp of Sanders, Warren, Booker and Klobuchar, who all believe organized labor’s decline can be reversed, and who think, said Bernstein, that “the power of capital and its ability to block collective bargaining is outlandishly high and needs to be pushed back on … He needs to get into the fray.”

* * *

At the SEIU conference, after a full afternoon of courting by the candidates, Dawn Fitzgerald, a lab worker at Oregon’s Providence Portland Medical Center for 24 years, dismissed Biden as “a corporate money type.” Fitzgerald, who moonlights as a singer in a retro-pop duo and favors Sanders, said she even got a kiss from Cory Booker. “That’s worth a vote,” she joked as she and two co-workers reflected on the day. Then, Fitzgerald quickly ruled out Booker because of his pro-nuclear power stance.

But Fitzgerald, along with Stephanie Shufelt, who checks in patients at the same hospital, and cook Charlene Cox, all agreed with Biden that they were “being clobbered”; they’re hoping that the 2020 election and the union contract they’re fighting for will stop the assault. Both Cox and Shufelt lean toward Sanders or Warren.

“There’s not a person in my department that qualifies to rent an apartment,” Shufelt said, noting that Portland’s average monthly rent is $1,500.

Workers may be hurting more than they have in decades, while their unions are at their weakest. Only about 11 percent of U.S. workers are unionized, but their issues are on the presidential candidates’ agendas, and the labor movement is enjoying a newfound popularity, which is “inversely related to the power and size of unions,” said Nelson Lichtenstein. A general hostility toward once-powerful unions has diminished, he said: “Now they’re weak, so unions have become a kind of metaphor for inequality and wage stagnation.”

Where the SEIU threw its support behind Hillary Clinton more than a year before the 2016 election, now a spokeswoman says the union is not in a hurry to endorse and is instead allowing its members time to listen to the candidates and participate in the process.

Other unions are also hanging back, giving their members opportunities to weigh an unprecedented array of options, signaling that if Biden wants to win significant union support in 2020, he can no longer coast on his previous close ties with organized labor.

Copyright Capital & Main