Labor & Economy

Retirement Board Facing Critical Pension Decision

Within the next 20 years, the number of Californians beyond retirement age will increase by two-thirds, to 12 million. Many of them — half, by some estimates — will have saved less than they need to subsist on after they stop working, leaving them no choice but to either work until the end of their lives if they can, or live out the rest of their years in or near poverty.

Some of those seniors of tomorrow, no doubt, were during their working lives too short-sighted to invest in their employers’ 401(k) plans, or to open Individual Retirement Accounts (IRAs) on their own. Or they might have been struggling to support families, pay back student loans or were so chronically underemployed that saving money for retirement was out of the question.

See Also — Retirement: A California Mirage?

In 2012, state legislators recognized this looming problem of the future elderly poor and wrote the California Secure Choice Retirement Savings Trust Act, establishing a low-cost retirement savings plan for all private-sector workers whose employers don’t already offer one. Authored by Senate Pro Tem Kevin de León (D-Los Angeles) and signed into law by Governor Jerry Brown that September, the bill created a consortium of financial experts from academia, legal firms and insurance companies to evaluate the risks and rewards of a state retirement-savings plan, and to determine how to invest participants’ money.

The consortium issued its report March 17. Among its findings: Of the 6.8 million workers potentially eligible for the state retirement program, 70 to 90 percent would likely participate in a program that deducted as much as five percent of their after-tax income for retirement savings. The program would be “financially viable and self-sustaining,” the analysts concluded, “even under adverse conditions, with poor investment returns.”

The Obama administration has floated a similar retirement-savings proposal, called MyIRA. Like California Secure Choice, it offers people a government-managed, guaranteed savings plan — a low-cost alternative to the traditional IRA. But the federal program suffers from one critical difference: It’s voluntary.

“People would have to make an affirmative decision to join,” says Teresa Ghilarducci, professor of economics at the New School, where she directs the university’s Retirement Equity Lab. “We don’t expect that to do much for participation rates.”

The California program, by contrast, would require employers with five or more workers to automatically enroll their employees, and begin deductions without their employees’ prior consent. “It takes advantage of inertia,” Ghilarducci says.” Workers could opt out, but even if some do, opt-out programs increase participation rates over voluntary programs “by a factor of hundreds.”

The opt-out provision, nevertheless, is also the weakness in California’s program, as is its current exclusion of independent contractors (although the program may extend to them in the future). That’s because the most successful retirement program operates just like health insurance: Everybody’s in. “Social Security would have been a disaster if there was an opt-out,” notes Ghilarducci. “There are just some things that we all need to participate in so we don’t cause a huge cost to ourselves and society. It’s just the price of living in an advanced society where people don’t work until they die.”

This is one of the ways in which the 401(k) program, which the U.S. Congress established in 1978, has failed, Ghilarducci says. In part because the retirement savings scheme has been voluntary, “it has never gone beyond covering half of the workforce.” Fees associated with a commercial program, plus a volatile stock market, have stood in the way of people saving as much as they need. Nor does a 401(k) guarantee a steady flow of income throughout the years – retirees have the option of taking their money in a single lump sum.

“A good retirement system helps people accumulate, invest in a safe and low-cost way, and [then] de-accumulate with a lifelong string of monthly income,” Ghilarducci says. The current system does none of that.

California’s retirement program succeeds in all those ways. Sarah Zimmerman, program director for Retirement Security for All California, thinks it should be attractive even to low-income workers in their late 50s with only eight to 10 years of their working lives to contribute. “They can use it to delay Social Security,” and thus maximize their federal benefits, she says.

But will workers just scraping by on the edge of survival want to spare five percent of their income to save for the future?

“Probably not,” she says. “That’s always the rub with retirement savings. If you’re not paid a living wage, it makes it very difficult to save for retirement. So let’s hope we get to a $15-an-hour minimum wage this year.”

On March 28, the state Retirement Board will vote to decide on the particulars of the California Secure Choice plan. The consortium has presented two options: A “target-date” fund, in which investment risk shifts from high to low as a worker’s retirement day nears, or a pooled IRA plan with a reserve fund, in which investment risk is shared among participants and spread over time.

The target date option is a common investment strategy in 401(k) plans, says Nari Rhee, manager of the Retirement Security Program at the University of California, Berkeley Center for Labor Research and Education. Rhee, who served on the consortium, admits that it entails more risk. “It’s like if you had a 401(k) and retired in 1999, you did well; if you retired in 2001, not so well.” (And you probably shouldn’t have retired in 2008 if you could have avoided it.)

The pooled IRA plan puts everything participants earn over a certain percentage in a given year and deposits the excess in a reserve fund. If returns dip too low in a given year, the reserve fund can be used to level out earnings. “It smooths returns across retirement cohorts,” Rhee says, “to minimize the risk if you retire in a year when the market tanks.”

The pooled investment model was developed at the Center for American Progress, a progressive think tank; because it’s never been done before, it will take more personnel and expertise to get it started. But Ghilarducci strongly recommends that the board adopt it. “They should choose the plan that smooths returns,” she says, “not the one that mimics commercial individual retirement plans. Those plans are too expensive and too risky.”

In either case, the consortium report leans heavily toward investing funds in a Roth IRA, as opposed to a traditional IRA. Contributions to a traditional IRA are tax-deductible, but subject to taxes when they’re withdrawn after retirement. Roth IRA contributions aren’t deductible, but they’re paid out tax-free after age 65. That last part matters to more than half of the workers eligible for the retirement plan: Fully 42 percent of eligible workers — those without employer-sponsored retirement plans — are in the zero percent tax bracket, and another 16 percent are in the 10 percent bracket. Tax deductions don’t mean much to them during their working lives.

Higher income workers might opt out of a Roth IRA-based retirement plan, but they also often have more options. If the California proposal caters to low- or middle-income workers, it’s because that’s where the need is.

And there is, Ghilarducci insists, a great need, in California and other states. Without low-cost retirement savings plans available to all, “state and local governments will have to subsidize and pay for poor or near-poor elderly over the next 20 years as the Baby Boom ages.” They will pay out in direct costs — Meals on Wheels, Medi-Cal costs, emergency food and emergency housing for older people. They will pay in hard to quantify but very real indirect ways, such as the cost of forcing elderly people out of their homes because they’re too poor to keep them.

Finally, “there’s a cost to moving away from the values of our society,” Ghilarducci says. “With Social Security we took on the responsibility that we would give workers an easy way to save for themselves for old age. With the tax breaks for an employer plan, we took on the responsibility to have people provide for themselves in old age.

“What California is doing is recognizing that the voluntary, individual-directed, commercial system that sits on top of Social Security, deeply subsidized by federal and state governments, has failed. It’s time to do something about that failure.”

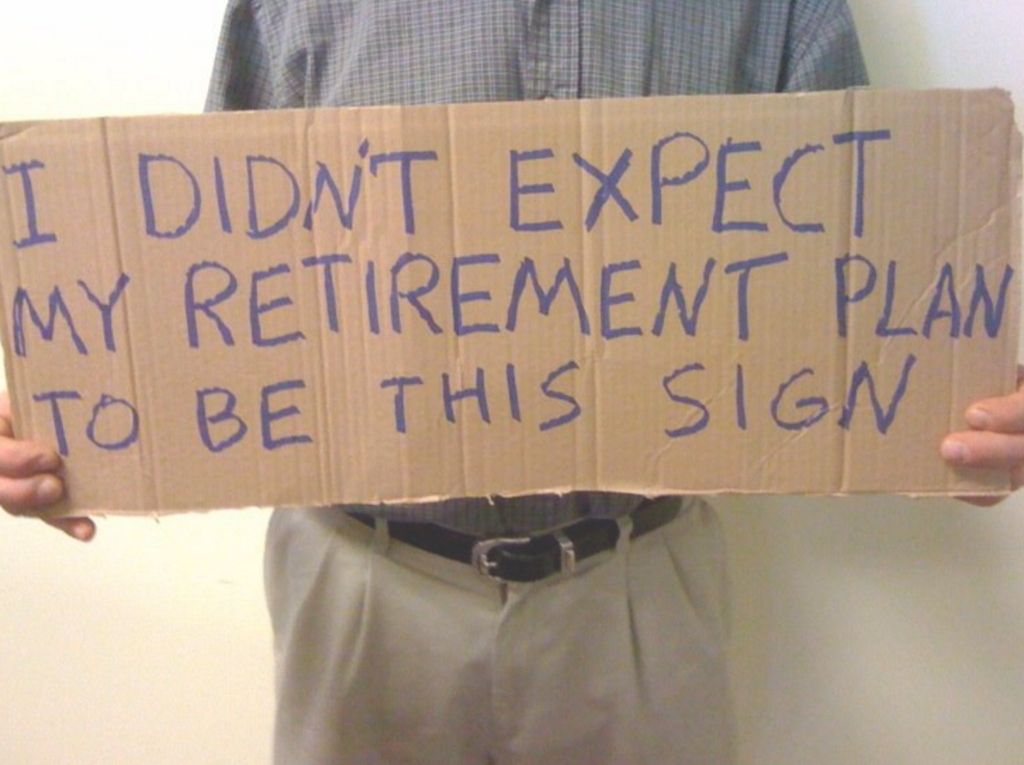

(Photo: “Wikipediuh”)

-

State of InequalityApril 4, 2024

State of InequalityApril 4, 2024No, the New Minimum Wage Won’t Wreck the Fast Food Industry or the Economy

-

State of InequalityApril 18, 2024

State of InequalityApril 18, 2024Critical Audit of California’s Efforts to Reduce Homelessness Has Silver Linings

-

State of InequalityMarch 21, 2024

State of InequalityMarch 21, 2024Nurses Union Says State Watchdog Does Not Adequately Investigate Staffing Crisis

-

Latest NewsApril 5, 2024

Latest NewsApril 5, 2024Economist Michael Reich on Why California Fast-Food Wages Can Rise Without Job Losses and Higher Prices

-

California UncoveredApril 19, 2024

California UncoveredApril 19, 2024Los Angeles’ Black Churches Join National Effort to Support Dementia Patients and Their Families

-

Latest NewsMarch 22, 2024

Latest NewsMarch 22, 2024In Georgia, a Basic Income Program’s Success With Black Women Adds to Growing National Interest

-

Latest NewsApril 8, 2024

Latest NewsApril 8, 2024Report: Banks Should Set Stricter Climate Goals for Agriculture Clients

-

Striking BackMarch 25, 2024

Striking BackMarch 25, 2024Unionizing Planned Parenthood