Jimmy Wilson, a 49-year-old cook who works at a Detroit bar, is sitting outside on his break and fuming. “This doesn’t affect me at all,” he says, speaking about the Democratic debates streaming on the bar’s TVs. “I still have to go to work in the morning. I still have to pay taxes.”

Wilson’s Corktown neighborhood has been flourishing recently, attracting new shops and townhomes. But he worries that rising prices and new arrivals might push him out of what has historically been a working-class community. And he’s angry that he labors six days a week and doesn’t have more to show for it. “I should have the same opportunity that a kid that grew up in Bloomfield Hills has,” says Wilson, referring to an affluent Detroit suburb.

Does the Democratic Party’s leftward tilt signal a will to finally confront economic inequality?

Most political observers agree that it will take far more than a presidential election to reverse a trend that have been in the works since the 1970s. But advocates see hopeful signs coming from candidates willing to talk about making major changes to an often undemocratic political system, as well as about ambitious economic plans.

A crop of Democratic presidential candidates is pushing policy proposals aimed squarely at America’s Jimmy Wilsons, those who work hard but feel they are not getting their fair share of the pie. And, amid Gatsby-era levels of economic inequality, there are more of them than ever.

But some believe the booming economy is Trump’s to own.

“I’m not sure if the Democrats really want to talk about the economy. They need to talk about leadership,” says longtime political consultant Mario Morrow, finishing up his burger at Clique, a popular diner in downtown Detroit. “If someone did not have a job four years ago and they have a job now, they are better off.”

* * *

Progressive candidates argue that a more transformative economic program is needed to address the daily struggles of Americans and that such policy proposals can offer up a winning strategy in the high-stakes battle to prevent Trump from securing a second term.

On the policy menu of some of the top-tier candidates are populist economic proposals considered radical only four years ago: a wealth tax, breaking up the big banks, tuition-free college and Medicare for All. So, is Jimmy Wilson’s cynicism justified—or does the Democratic Party’s leftward tilt signal that the country is finally ready to tackle economic inequality?

Minority Americans suffer from a staggering wealth gap with whites that

leaves them little to fall back on.

If Americans are better off than they were a decade ago, it doesn’t always feel that way. The recovery from the Great Recession has been slow and uneven, with low-income Americans—many of them Latino, like Wilson, or African-American, like Detroit auto worker Steve Jennings—experiencing fewer of the benefits. As a group, minority Americans suffer from a staggering wealth gap with whites that leaves them little to fall back on.

Jennings earns $13.75 an hour as a materials handler at Kace Logistics, a company that prepares auto parts for assembly. It’s a job that leaves him “sweating, sweating,” even in winter. He’s been there six years and earns $3 per hour less than he did at a previous job, which he says he left after an injury there.

When Jennings goes to the doctor, he faces co-payments of “$50 almost every visit,” even though employees at his firm are represented by the United Auto Workers. “You’re not paying me enough to be buying the cars that I’m making,” says Jennings, who drives a 1997 Oldsmobile Aurora.

Today Jennings dashes out to buy work boots at a mall in nearby Highland Park, the city that birthed the modern assembly line and whose median household income of $15,699 has declined over the past five years. The mall is home to discount stores, a CVS, a payday lender and one of the original Model T factories, now in disrepair.

Things were different for his parents. Even with his father’s single income, “We never went without anything,” he says.

* * *

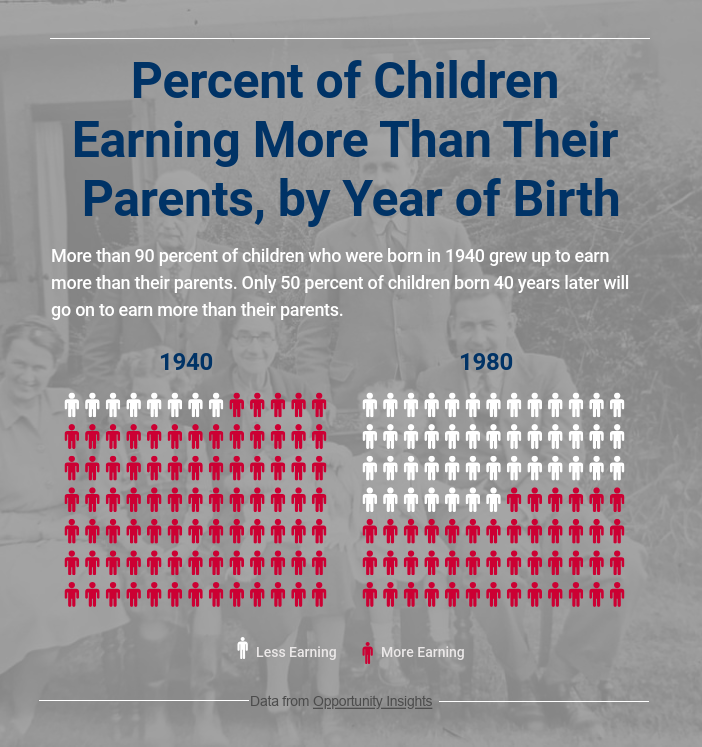

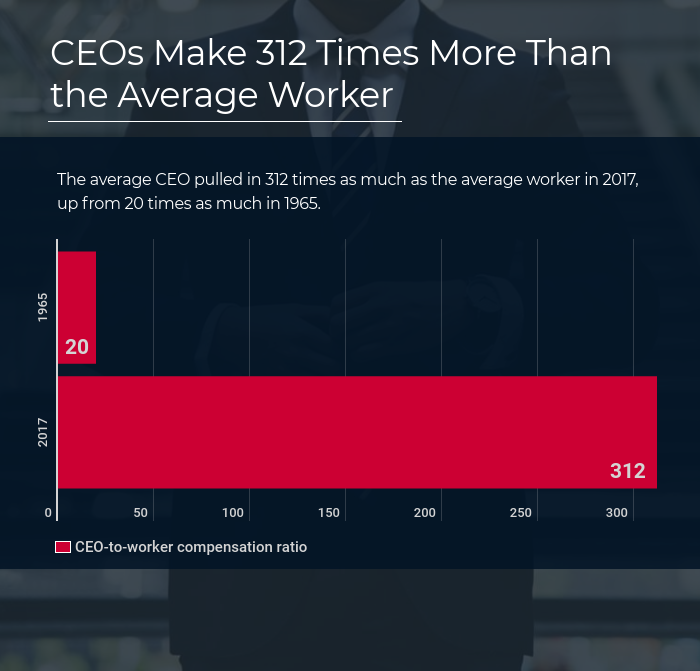

Jennings’ lament touches on a reality felt across the country. Economic mobility is on the decline, according to a Harvard team of researchers led by economist Raj Chetty. More than 90 percent of children who were born in 1940 grew up to earn more than their parents. Only 50 percent of children born 40 years later will go on to earn more than their parents. But the top one percent is doing better than fine: The average CEO pulled in 312 times as much as the average worker in 2017, up from 20 times as much in 1965, according to the Economic Policy Institute.

The rise in economic inequality is a global phenomenon. But it is more extreme in the U.S., where social mobility has been shown to be lower than in other industrialized nations, and where the safety net is weaker and poverty more severe. Even though the U.S. spends more per capita on health care, the system covers fewer people and produces worse outcomes, including lower life expectancy and higher infant mortality rates.

If the United States had experienced the same decline in infant deaths as have other Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development member states since 1960, 300,000 fewer babies would have died over the course of 50 years, according to a recent report.

Moreover, the U.S. has seen life expectancy drop during the past three years, the longest consecutive decrease since a period that included World War I and a concurrent flu pandemic. The grim combination of a rising suicide rate, especially in rural areas, and an epidemic of drug overdoses deserve the blame, say experts, but so may accelerating economic inequality.

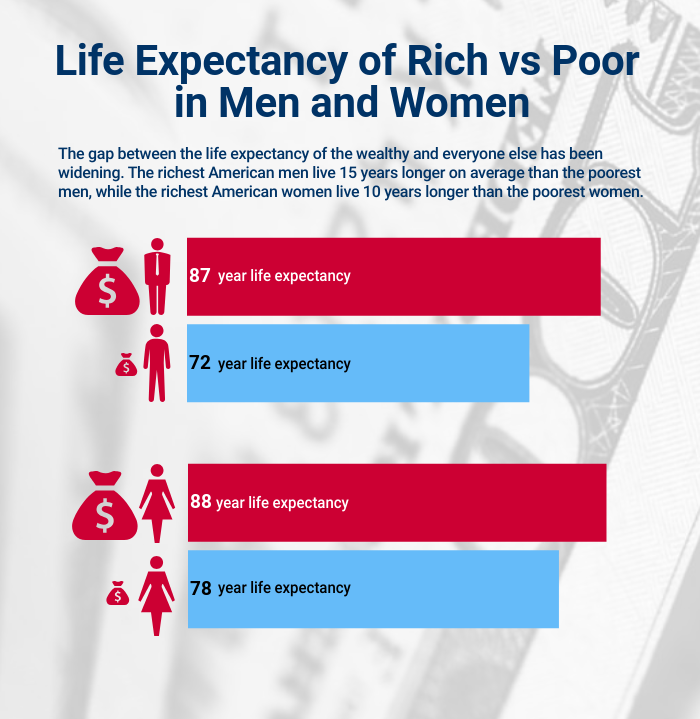

At the same time, the gap between the life expectancy of the wealthy and everyone else has been widening, according to a 2016 study by Chetty published in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

Tackling economic inequality—and its potentially lethal effects—will require a “one-two punch,” says Steph Sterling, vice president for advocacy and policy at the Roosevelt Institute, a liberal, D.C.-based think tank. That requires putting a check on increasingly powerful corporations—the Amazons, ExxonMobils and Walmarts—and expanding government’s role where markets fail to provide for the public good.

Senators Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren have in different ways taken that pugilistic approach. Warren has produced a raft of policy initiatives—including putting workers on corporate boards, enacting a wealth tax and antitrust legislation—that are intended to address racial and economic inequality and to curb corporate power.

For years Sanders has made himself Wall Street’s nemesis. Like Warren, he proposes breaking up the large banks, and he wants to hike the estate tax. He has been the leader in promoting Medicare for All and free college, ideas he regularly points out were considered outside the mainstream until only recently.

* * *

Sanders and Warren have company in the form of candidates who have tacked left. Senator Kamala Harris advocates rolling back the Republicans’ 2017 tax cuts and providing tax breaks to the poor and middle class. Other candidates have backed a tax on financial transactions in the stock market and supported a federal jobs guarantee.

But a potentially disruptive reform agenda requires broad public support. Americans are legendary for their individualist streak and, in recent history, for their distrust of the federal government. Polls, however, also show a country that is wary of the size and influence of corporations, and in which large majorities—including low-income Republicans—support increasing the federal minimum wage to $15.

The structure of American political institutions is notorious for giving opponents many ways to stop major change.

What’s more, support for labor unions is at a 15-year high.

Still, with membership about half of what it was in 1983 (the first year for which comparable union data are available), there are simply fewer work boots on the ground to push for more egalitarian economic policies.

And maintaining public support for a reform agenda is not the only challenge. As Pete Buttigieg told the packed and cheering Avalon nightclub in Hollywood last summer, “We’re not the democracy we think we are.” He was addressing supporters and those still shopping for Democratic presidential candidates. Buttigieg singled out the pernicious effects of gerrymandering that allow politicians to pick voters “and not the other way around.”

There are other, less visible roadblocks to enacting a major legislative agenda. The structure of American political institutions, with the division of political power and strong federalism, is notorious for giving opponents many ways to stop major change. And corporate lobbyists’ power and numbers have grown exponentially in recent decades. Even in earlier times, the federal government has often refrained from tackling economic problems. Nearly three decades followed passage of the first state minimum wage before adoption of a national minimum wage in 1938.

Has Trump’s presidency—and the anguish it has caused immigrants, women and others —made space for a more far-reaching progressive policy agenda?

“It does take a long time for this [reform] process to work its way up to the federal level, and sometimes it takes a disaster for big policy changes to actually be made,” says William Franko, a political scientist at West Virginia University and co-author of The New Economic Populism.

Not everyone is pessimistic. “A lot could come of this moment,” says Aimee Allison, founder of She the People, a national network of women of color, which sponsored the first town hall for Democratic presidential candidates. She is among those who say that Trump’s presidency—and the anguish it has caused immigrants, women and others —has made space for a more far-reaching progressive policy agenda. “It’s in this environment,” Allison says, “where ideas of economic change that were looked at as crazy just two years ago are now a part of regular conversation.”

Regardless of whether major progressive reforms can be won in the next few years, there is no downside to discussing proposals that are ambitious enough to address the challenge at hand, says Erik Loomis, a University of Rhode Island historian, who cautions against voters investing too much faith in what one president can do on his or her own.

“The idea that that Democrats can tack moderate and somehow attract voters and create a program is simply a Beltway construction that is completely disconnected from how actual voters operate,” he says.

That’s certainly a red-hot topic of debate among political analysts, some of whom see Biden’s support as a sign that voters desire a return to bipartisanship, centrism and civility. The bigger question is whether skeptics like Jimmy Wilson are justified, or whether the American political system can be harnessed to narrow an economic chasm that has so many struggling to pay bills and some dying years before their time.

Illustration by: Design Urban

Infographics by: Joanne Kim

Copyright Capital & Main