Society

Homeless Deaths Are on the Rise: L.A. County Officials Ask Why

California’s homeless crisis has been fueled by gentrification and an affordable housing shortage that is especially acute in such job-rich urban areas as Los Angeles and San Francisco.

Daniel Duarte, described by his sister as “artistic and intelligent,” was one of the 917 homeless people in Los Angeles County who died in 2018.

Like too many homeless people, Duarte, a father of a 2-year-old girl, died violently, shot in what police told reporters was a random, gang-motivated attack while living in a homeless encampment on the Arroyo Seco flood control channel in Northeast Los Angeles. Most homeless people – nearly 60 percent—did not die of natural causes in 2018.

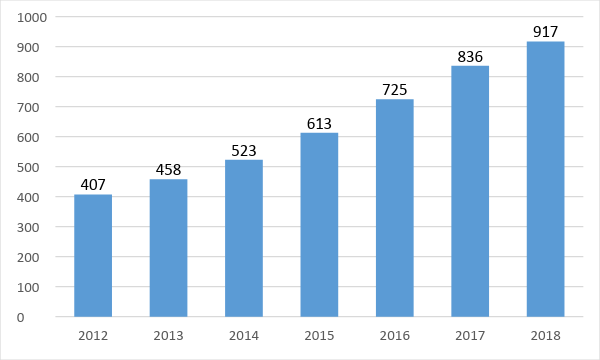

This year’s 10 percent increase in homeless deaths over last year’s is noteworthy because the total number of homeless people in the county declined by four percent between 2017 and 2018.

County officials are trying to understand what is behind the rise in the number and rate of homeless deaths. In 2010, the rate of death for every 10,000 homeless people in the county was 111; last year it was 174.

Key statistics

- Homeless deaths in 2017: 836

- Homeless deaths in 2018: 917

- Number of homeless people in LA County in 2017: 55,048

- Number of homeless people in L.A. County in 2018: 52,765

- Rate of death per 10,000 homeless in 2010: 111

- Rate of death per 10,000 homeless in 2018: 174

All manner of mortality—suicide, deaths from natural causes, homicides, and death by accident—have been increasing over the past six years, according to a presentation the Los Angeles County Department of Medical Examiner-Coroner made to deputies from the offices of the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors earlier this month. The type of death that has seen the biggest rise, however, is accidental death, and the most commonly reported accidental death is a drug overdose.

The rising number of deaths due to drug overdoses may be linked to the national opioid epidemic, although it is too soon to tell for sure, according to Will Nicholas, director of the L.A. County Center for Health Impact Evaluation. He is working to match information available on death certificates issued by the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health with data collected by the coroner’s office. The coroner does not investigate every death in the county, but is more likely to look into deaths in the homeless population, according to Nicholas.

“Homelessness is at crisis levels in L.A., so we’re interested in learning what we can about causes of death among the homeless, so we can better target our health-care resources,” says Nicholas, whose center is part of the L.A. County Department of Public Health.

* * *

California’s homeless crisis has been fueled by gentrification and an affordable housing shortage that is especially acute in such job-rich urban areas as Los Angeles and San Francisco.

The lack of shelter is felt keenly by older people, who, according to Nicholas, are becoming an ever larger part of the homeless population, which may also explain the escalating death rate.

Homeless Deaths Have Been Rising in Los Angeles County

Source: Los Angeles County Coroner’s Office

The oldest homeless Angeleno to die last year was an 87-year-old woman who passed away in a hospital in Pasadena of congestive heart failure, according to the coroner’s database. The youngest: an 8-week-old baby, who perished in his mother’s arms while she was nursing him on a Los Angeles city bus.

Homeless people were 15 times more likely than the general public to be victims of homicides in 2017, according to this month’s coroner’s office presentation. The rate of suicide was more than nine times higher, and the rate of accidental deaths – including drug overdose or alcohol poisoning – was 25 times as high. January is the deadliest month to be homeless, beating out December and July by small margins, according to five years of data analyzed by the coroner’s office. Two-thirds of homeless people were men in 2018, but men accounted for four-fifths of the deaths among the homeless.

Frederick Murphy, a graffiti artist and activist who has been homeless for eight months, can attest to the perils of living on the street. He’s always on his guard and feels as though he’s a target because he is young and has possessions, including the surf board on which he is painting a stylized “God Save LA.” Murphy became homeless after breaking up with his live-in girlfriend, and getting priced out of a downtown loft he shared with two roommates.

“You can’t trust anyone on the street,” says Murphy, who, in his black cap and tapered pants, looks like he could fit in at one of Echo Park’s nearby coffee shops. “I have to keep a knife around, which is not a good thing for me.” Murphy, who says he is on a wait-list for housing, also complains of harassment by police and of having his tent damaged in the recent rains.

Earlier in the day, adds Murphy, who is 31, confronted another homeless man rummaging through his tent, who threw a stick at him. He lifts his shirt and reveals a v-shaped cut on his pale chest.

Half a mile away, in Angelino Heights, the blue and white flowers have wilted on two heart-shaped wreaths laid at the address where a 33-year-old woman was found hanging from a tree in mid-December. Candles had been lit at a gathering about two weeks ago outside a house with broken windows, where people had been squatting, according to Leticia Monreal, a neighbor who was walking her dog. “It’s been like that for years,” Monreal says, referring to squatters. The house is now surrounded by a new-looking chain-link fence that is locked with a padlock.

Copyright Capital & Main

-

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026Amid the Violent Minnesota Raids, ICE Arrests Over 100 Refugees, Ships Many to Texas

-

Featured VideoFebruary 4, 2026

Featured VideoFebruary 4, 2026Protesters Turn to Economic Disruption to Fight ICE

-

The SlickFebruary 2, 2026

The SlickFebruary 2, 2026Colorado May Ask Big Oil to Leave Millions of Dollars in the Ground

-

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 5, 2026

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 5, 2026Lawsuits Push Back on Trump’s Attack on Child Care

-

Column - California UncoveredFebruary 6, 2026

Column - California UncoveredFebruary 6, 2026What It’s Like On the Front Line as Health Care Cuts Start to Hit

-

The SlickFebruary 10, 2026

The SlickFebruary 10, 2026New Mexico Again Debates Greenhouse Gas Reductions as Snow Melts

-

Latest NewsFebruary 12, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 12, 2026Trump Administration ‘Wanted to Use Us as a Trophy,’ Says School Board Member Arrested Over Church Protest

-

Latest NewsFebruary 10, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 10, 2026Louisiana Bets Big on ‘Blue Ammonia.’ Communities Along Cancer Alley Brace for the Cost.