ILL HARVEST

Falling Through the Cracks

An historic expansion of Medi-Cal for undocumented workers will miss many farmworkers.

Luis Lopez, 50, who has worked the strawberry fields in Santa Maria, California, for the last couple of decades, recently received good news: He was now eligible for full Medi-Cal coverage and had been automatically enrolled in the program by the state.

For the first time since he arrived in this country as an undocumented worker, he could breathe easier knowing he had health care coverage. “I feel lucky,” he said recently.

Lopez is one of the 286,000 undocumented Californians over 50 who recently gained full coverage under Medi-Cal, California’s public health insurance program that services low income individuals. Before the current expansion, most undocumented people in the state could get only restricted Medi-Cal, which only covers emergencies and, in the case of women, services relating to a pregnancy.

This expansion has been a commitment of Gov. Gavin Newsom and represents the work of many legislators past and present, as well as a coalition of community groups, the Health4All Coalition, that worked on it for more than a decade.

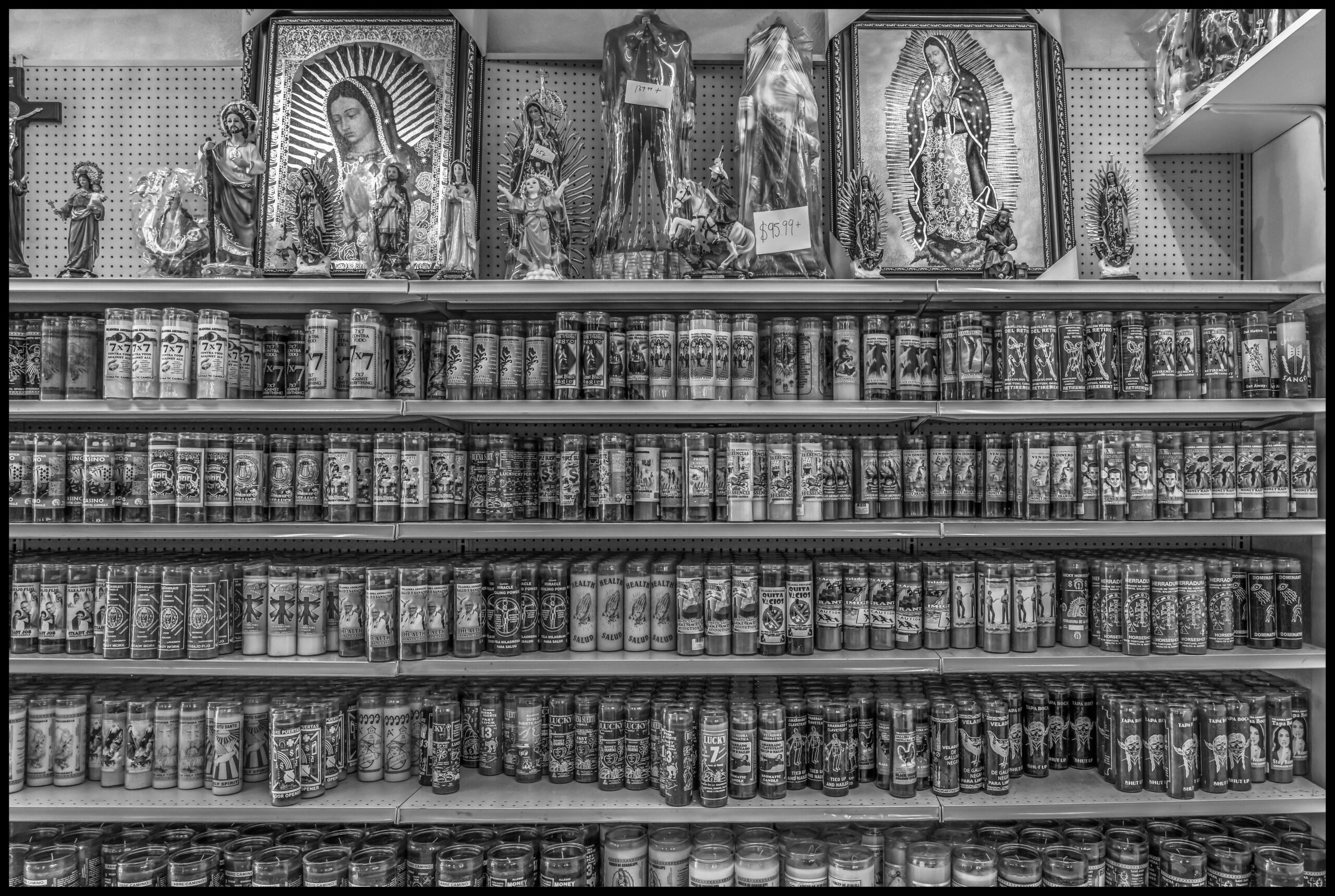

Before this coverage reached him, Lopez had avoided private or public clinics due to the potential cost; he talks about regularly using the local botánica to buy pharmaceuticals brought from Mexico.

“I just got the flu recently, and I paid $40 for four shots of eucalyptus at the local store; it’s better than paying $400,” he says, referring to a common treatment in Mexico for respiratory infections, the injectable cough medicine Eucaliptine. “But if the illness is serious, one runs a risk.”

The recent Medi-Cal expansion is good news for people like Lopez. But even after the full expansion occurs in January of 2024, to include undocumented farmworkers between 26 and 49 years old, advocates and researchers warn that there will still be a big gap due to income eligibility.

Lopez said he is aware that he was eligible thanks to his family of five. With his income of $2,500 per month, he needed at least two dependents to be able to get coverage for himself.

Farmworker Luis Lopez.

“I have four dependents; if it weren’t because of that … I would supposedly make too much to get it,” he said, adding that his wages “barely cover the rent.”

Others haven’t been that lucky. Thirty-two-year-old Sara Renteria, a date-packing worker in the Coachella Valley, said her dad, a farmworker in Mecca, California, was told he did not qualify for the benefit.

“He tried to get it but didn’t qualify,” she said. “He is 51 years old and makes minimum wage — which in California is $14 an hour. He makes about $600 per week and sometimes works on Saturdays.”

Eligibility for Medi-Cal is based on the federal poverty guideline. For an adult to qualify, he or she must make less than 138% of the poverty level. “Which means if you’re an individual making more than about $18,700 a year, you’re out. A family of four is $38,300, and you are out,” said Joel Diringer, a consultant researcher for a study completed this year that concluded that around 40% of farmworkers, many of them undocumented, would be unable to take advantage of the expansion due to income. “Farmworker Health in California,” a study funded by the California Department of Public Health and The California Endowment, and conducted by researchers at the University of California, Merced, surveyed over 1,100 workers and studied health access and utilization.

A previous health coverage expansion implemented after 2014, following the passage of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), did benefit farmworkers, but mostly documented ones, concluded a report released by the Public Policy Institute of California (PPIC) in April of 2022.

“For documented farmworkers there was an increase in 2014, but we didn’t see anything like that for the undocumented ones,” said Paulette Cha, principal author. The report does not include any expansion since 2020. “We don’t know the impact yet.”

Votive candles and religious statues at the Botanica Juquila in Santa Maria.

Being a farmworker is tough, back-bending work. In California, average income for farmworkers is about $500 per week: too much for an individual worker to qualify for Medi-Cal but not adequate given California’s high cost of living, said Cristel Jensen, a staff member for the California Institute for Rural Studies.

“The fact that they are telling farmworkers that they don’t qualify because they make too much money is not a supportive way to tell farmworkers, ‘Your health is our priority, and we want to take care of you.’”

The UC Merced report examined broadly the challenges facing farmworker health and it concluded that policymakers need to further expand access and close the loopholes in access that affect farmworkers.

Some of their challenges are unique to their profession, said Paul Brown, co-author of the report and an economist at UC Merced. “We know from research over time that farmworkers face special problems that other people who are just not documented don’t face necessarily.”

One of those problems is losing Medi-Cal eligibility due to income fluctuations throughout the year, explained Alondra Mendoza, a community health worker or promotora for the Mixteco/Indígena Community Organizing Project.

“In fieldwork, the salary is not something stable. Sometimes the fruit is good, and workers are earning well for a week or several weeks, and then it’s over. That’s where the health system still needs to improve,” she said, noting that increases in income can suddenly put workers over the eligibility threshold.

The UC Merced study has already fueled further research as well as discussion among California policymakers, who increasingly believe they need to reassess the plight of farmworkers if the state is to meet Gov. Newsom’s promise of universal access to health care coverage regardless of immigration status.

Religious statues at the Botanica Juquila in Santa Maria.

Democratic Assemblymember Joaquin Arambula, a former emergency room doctor who represents Fresno and surrounding rural areas, says that one possible solution would be for the federal government to issue a waiver allowing undocumented residents to purchase coverage through the state’s Affordable Care Act marketplace, better known as Covered California.

When the Affordable Care Act was passed in 2010, undocumented residents were left out and unable to purchase coverage though the ACA marketplaces.

Along with state Sen. Maria Elena Durazo (D-Los Angeles), Arambula sponsored the legislation that authorized the various expansions of Medi-Cal during budget negotiations with Gov. Newsom over the last few years.

Asking for such a federal waiver to allow farmworkers to buy into Covered California with subsidies is something that former state Sen. Ricardo Lara, one of the champions of removing all exclusions in access to health care, had been considering a few years ago.

But California legislators abandoned their efforts when Donald Trump won the presidential election in 2016, knowing there would not be support for it in Washington, said Arambula.

Another possible way to address this issue is to increase the income levels required to qualify for Medi-Cal, in order to be consistent with the wages and the cost of living in California, said Diringer.

A combination of those two moves “should cover most farmworkers,” he added in an email.

When Lara, the son of undocumented workers and now the insurance commissioner of California, was a state senator, he worked with the Health4All Coalition to introduce SB 1005 in 2014. It would have extended Medi-Cal to everyone under 138% of the poverty level. But the ambitious bill failed to pass, and advocates and policy makers decided to push little by little, said Jose Torres, policy and legislative advocate of Health Access California, part of the coalition, explaining why they pushed the effort in parts.

Various estimates indicate that close to 60% of farmworkers in California are undocumented, and they have no Medicare waiting for them in their golden years. Experts believe farmworker health issues are likely to be exacerbated in the coming years due to public health crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic and climate change, which will manifest in increasingly severe and frequent heat waves and wildfire smoke, among other ill effects.

A Historic Expansion, Long Overdue

Farmworkers are among the most vulnerable populations in California, with some of the highest rates of infection and death from COVID-19. Theirs is one of the riskiest occupations in the state, and presents many barriers that prevent them from accessing good Medi-Cal coverage.

Stories about older farmworkers no longer working who are in ill health and have had no access to health care are common in the farmworking community.

“My former co-worker has been ill, with terrible headaches. Only her husband works now, and they are both undocumented and over 60,” said Francisca Meraz, a farmworker from Thermal, California.

Her friend went to a local clinic and ended up with a $200 bill. “And then the rent is $800, so they had to fall behind,” Francisca said. “I sometimes take her things I find cheap in the market to help out.”

Farmworkers like Meraz´s friend are now eligible for coverage, but whether they know it or feel they can navigate the health care system is quite another story, advocates say.

Herbs for sale at the Botanica Juquila in Santa Maria.

So far, a minority of undocumented farmworkers have benefitted from the Medi-Cal expansion as policy makers decided to implement it over time and by age. Only about a fifth of farmworkers in California are over 50 years old, and a similar proportion is under 26. The majority are between the ages of 26 and 49, and that group won’t get covered until January 2024. This phased expansion will eventually cover more than 1 million low income undocumented workers in the state.

State funds pay for these benefits, given that undocumented workers are not eligible for coverage under federal rules.

In 2019, California became the first state to extend full public medical coverage to all eligible undocumented young adults 18 to 25. Low income children have been covered, regardless of immigration status, since 2016. Illinois, Massachusetts, New York, Oregon and Washington state, plus Washington, D.C., also cover income-eligible children regardless of immigration status.

“We wanted everyone, regardless of documentation, to have coverage,” Health Access California’s Torres said, acknowledging that coverage must be followed by outreach and education about the benefits of coverage and ensuring that access to care is timely.

One big issue moving forward is outreach. “We are working with community organizations, local clinics and safety net providers to have the right flyers and information to share with community members.”

Waiting for Health Care

The entire expansion cannot come soon enough for most undocumented farmworkers in California, who are still not eligible because they fall between the ages of 26 and 49.

Fidel Santos, originally from Oaxaca, works in the strawberry fields in Santa Maria. He is only 38, but COVID hit him hard in 2020 as he kept working through the pandemic, like many of his fellow farmworkers.

“I was pretty bad. My oxygen level came down to 70%,” Santos said. “I didn’t go to the doctor; I just survived with medicine bought at the botanica. I don’t think the people in the botanicas are doctors, but they have their knowledge.”

He says he avoided the local clinics because of the potential cost.

Others tell of the lack of clinics and doctors, long waits that mean loss of a day’s salary, and discriminatory or rude treatment they sometimes endure in the Medi-Cal offices.

Renteria, the date-packing worker in North Shore, next to the Salton Sea in Coachella Valley, talks about trying to get a physical at a clinic in Mecca because both her parents have diabetes, and she fears inheriting that disease.

“I had an appointment at 9 a.m. I arrived 20 minutes early and waited several hours watching people come in and out. I waited four hours, and when I complained, the nurse was very rude. I then saw other people come in and get mistreated as well,” she said.

Assemblymember Arambula says he is aware of the shortages of health care workers in rural areas, such as the Central Valley. “We have half the number per capita than we do in Los Angeles and the Bay Area,” he said. Arambula is pushing locally to create a pathway program with peer mentoring to increase and diversify the workforce.

Getting People to Use the System

Informing people about the benefits and how to use them is the critical job of community health workers, better known in Spanish as promotores. The Mixteco Indigena Community Organizing Project (MICOP), headquartered in Oxnard, has a full-time team of nine promotores and program navigators to do this work every day, said Genevieve Flores-Haro, associate director.

“We do outreach to the community in various ways,” said Flores-Haro. “We have a good relationship with the county human service agency, so they send us the lists of people that were denied previously, and we reach out telling them they can now qualify. Also, our promotores speak English, Spanish and some of them, Mixteco.”

MICOP’s program is called Camino a la Salud (The Road to Health).

Alondra Mendoza, an outreach worker with MICOP, talks with a farmworker outside the Panaderia Susy in Oxnard early in the morning before work.

“We have outreach events in farmers’ markets and such. Also, sometimes we do ‘gran asambleas’ [large meetings] that directly advocate to the agricultural workers offering food and other help, and we have tables there to spread the information and workshops about how to use the Medi-Cal system,” said Nephtali Galicia, communications associate for MICOP.

Promotores call people between 4 and 6 p.m., aiming to reach them after they come back from the fields while respecting their time for dinner and tending to their families, said Juan Carlos Diaz, who speaks Spanish, Mixteco and English.

“Our work is to inform and educate our indigenous migrant community about health, how to access health services, how to demand their rights to access health care,” said Diaz.

One significant barrier is fear. Some call it the “ghost of public charge.”

Luis Lopez, the 50-year-old who just got enrolled in full scope Medi-Cal, already has an appointment for a physical but is wary of doing anything that may jeopardize his petition for legal status. He still wonders whether he should use the benefit at all. “I think I will ask my attorney before I go to my first appointment with the doctor,” he said.

The fear of using public services, common in undocumented communities, grew when then President Trump greatly expanded the types of benefits that can be a liability for people seeking to secure their legal residency in a policy known as “public charge.”

The Biden administration rescinded all of Trump’s policy, but its “ghost” still scares people away from using many services, even if they qualify, said Meredith Van Natta, a medical sociologist and assistant professor of sociology at the University of California, Merced.

Juan Carlos Diaz, an outreach worker with MICOP, talks with a farmworker outside the Panaderia Susy in Oxnard.

“This is still a major issue,” she said. According to immigration experts, enrolling in Medi-Cal does not affect immigration status or processes for immigration status.

Farmworkers have unique needs and challenges; that’s why Noe Paramo, a legislative advocate for the California Rural Legal Assistance Foundation, walked the state Capitol halls to find the money for the UC Merced study.

Paramo explains that advocates learned much more during COVID about why farmworkers are a unique population with their own needs.

“We appreciate the Medi-Cal expansion; it’s historic,” he said. “Now we must make sure that we make it work for farmworkers and their families.”

The data from the recent UC Merced farmworker study will be used to look at policy options to expand coverage specifically for farmworkers. A grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation is funding the effort, said the researchers.

“Now that we have numbers that tell you how many farmworkers may be left out of the Medi-Cal expansion, we will focus on how to fill those gaps to benefit them,” said Joel Diringer, one of the authors of the study.

“Some people in the Governor’s office seem to think the expansion that has been approved will take care of it all. But it won’t.”

All photos by David Bacon.

This series is supported by a grant from the California Health Care Foundation.

-

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026Amid the Violent Minnesota Raids, ICE Arrests Over 100 Refugees, Ships Many to Texas

-

Featured VideoFebruary 4, 2026

Featured VideoFebruary 4, 2026Protesters Turn to Economic Disruption to Fight ICE

-

The SlickFebruary 2, 2026

The SlickFebruary 2, 2026Colorado May Ask Big Oil to Leave Millions of Dollars in the Ground

-

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 5, 2026

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 5, 2026Lawsuits Push Back on Trump’s Attack on Child Care

-

Column - California UncoveredFebruary 6, 2026

Column - California UncoveredFebruary 6, 2026What It’s Like On the Front Line as Health Care Cuts Start to Hit

-

The SlickFebruary 10, 2026

The SlickFebruary 10, 2026New Mexico Again Debates Greenhouse Gas Reductions as Snow Melts

-

Latest NewsFebruary 12, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 12, 2026Trump Administration ‘Wanted to Use Us as a Trophy,’ Says School Board Member Arrested Over Church Protest

-

Latest NewsFebruary 10, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 10, 2026Louisiana Bets Big on ‘Blue Ammonia.’ Communities Along Cancer Alley Brace for the Cost.