Latest News

Commission Considers Freedom From Police Brutality a Human Right

A report on systemic racist police violence against Blacks in the United States is expected by the end of March.

In the aftermath of the death of George Floyd on May 25, 2020, and the ensuing worldwide protests, the American Civil Liberties Union in collaboration with Human Rights Network, the United Nations special rapporteur on Racism, Gay McDougall of the U.N. Committee on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination and others sent an appeal to the United Nations high commissioner for human rights asking for a special session of the U.N. Human Rights Council (HRC) and a commission of inquiry. It was a demand put forth in the name of the families of Black victims of police violence and over 600 advocacy organizations.

On June 19, 2020, a resolution to establish a commission of inquiry, like those that have recently investigated violations in Myanmar, Palestine and Yemen, was considered by the HRC.

The last words of 17-year-old Vincent Truitt to the officers who shot him in the back were, “Why did you shoot me?”

But, as some within the U.N. have noted, the Trump administration swiftly diluted key aspects of the resolution. HRC 43/1, as amended, veered from an in-depth look at the U.S. to a more general focus, and instead of an investigation conducted by a commission of inquiry, the high commissioner for human rights was tasked with preparing an annual report on systemic racism and violations of international human rights law. The first one is due in June.

Advisers to the Special Procedures of the HRC called the resolution “a diluted consensus resolution that would amount to lip service in the face of the urgency of this moment.”

“It’s almost impossible to hold the United States accountable,” says international human rights attorney Kerry McLean. “It won’t submit to the jurisdiction of the International Criminal Court, for example, and there’s only so far you can take matters against the U.S. in the Inter-American system. Though the U.N. as a structure is problematic, you use it in the ways that could potentially benefit you as an activist.”

* * *

Two days after the U.N. quashed hopes for a commission of inquiry, Lennox Hinds, a professor emeritus at Rutgers University, suggested to McLean that the coalition form its own. They could duplicate the familiar U.N. structure, enlist experts to serve as commissioners, hold hearings to give voice to people who’ve been struggling in the streets and courts for decades, document their findings in a rigorous report and deliver it to the high commissioner, Michelle Bachelet, by April 1 for use in her own report due in June.

“We’ve had a meeting with the high commissioner, and we’re hoping for a collaborative relationship and that the Office of the High Commissioner will use our report in hers,” McLean says. “We really want to see stronger language and action from the U.N. We think that the criticism and condemnation would have an impact, because right now the U.S. likes to go around acting like it’s the good guy sheriff of the world. We want to challenge that and hold the U.S. government accountable.”

“An unholy alliance between the prosecutors and the police has to be repaired, and the power of police unions must be confronted.”

— Sir Clare K. Roberts

Hinds and McLean brought in Jeanne Mirer, president of the International Association of Democratic Lawyers. IADL, the National Conference of Black Lawyers, and the National Lawyers Guild convened the International Commission of Inquiry on Systemic Racist Police Violence Against People of African Descent in the United States. With Hinds serving as coordinator, the commission was guided by an 11-member steering committee, and included 12 commissioners and four rapporteurs (to report on the hearings and write up the findings).

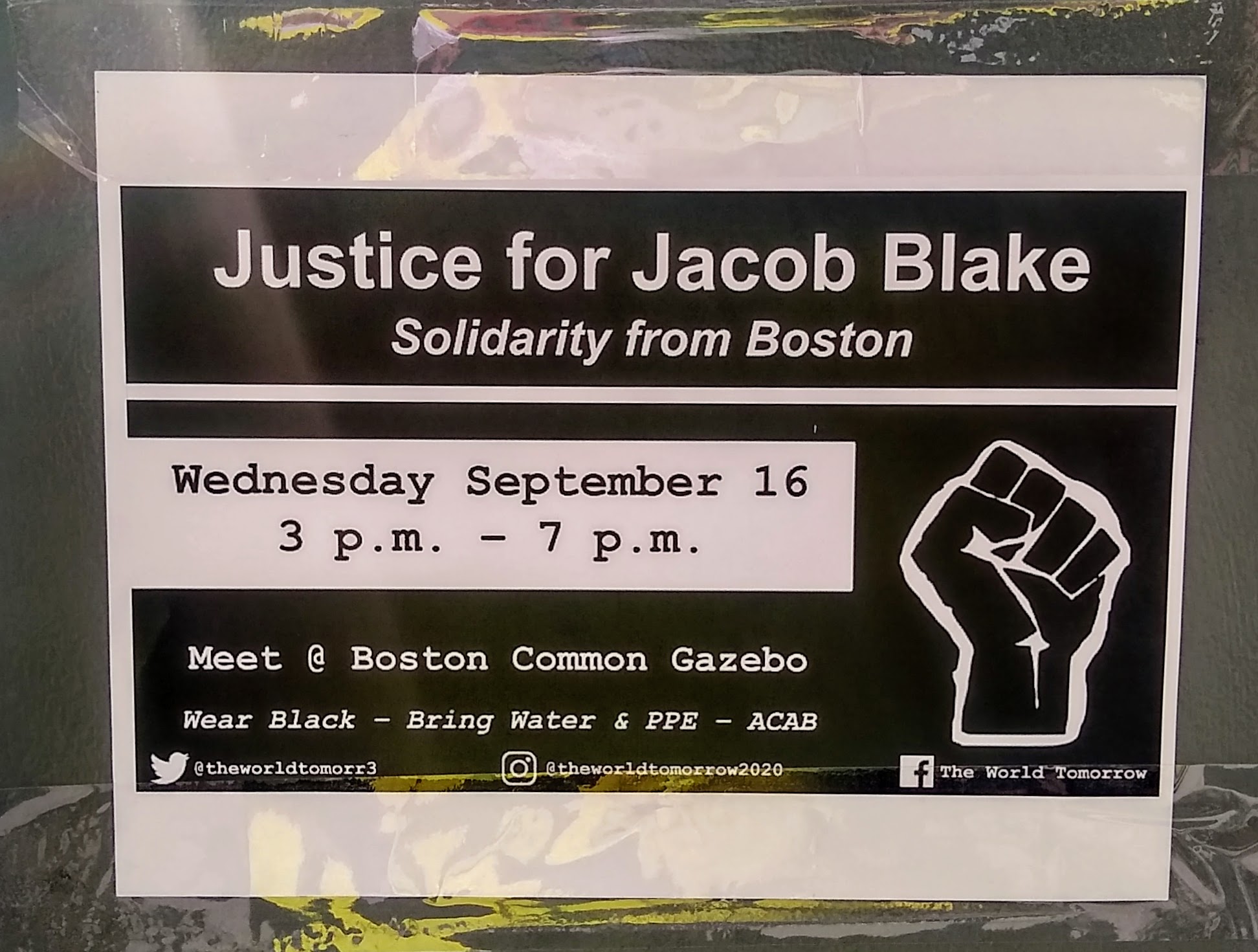

Dozens of families and attorneys offered testimony about what had happened to their loved ones in 44 cases from 2000 to 2020 in online hearings held from Jan. 18 to Feb. 6. Only one of these victims survived his assault: Jacob Blake of Kenosha, Wisconsin, a father of six who was shot in the back seven times in front of his children and is now paralyzed from the waist down.

Rapporteur Horace Campbell says the stakes could not be higher: “There’s a recursive pattern of police violence that we must break, and unless it breaks the society cannot move forward together.”

Campbell, a professor of African American studies and political science at Syracuse University, points to the example of Daniel Prude, who was killed by the police in Rochester, New York—a young man in the throes of psychosis, naked in the snow, who was surrounded by seven officers, cuffed and shrouded with a spit hood in which he suffocated. No criminal charges were brought for his death.

“Even when there was legislation and the attorney general got involved, the police were above the law,” he says. “There need to be more laws and political will put in place to change the nature of policing in this country.”

* * *

Based on the testimony, Sir Clare K. Roberts, one of the commissioners, expects the rapporteurs will spell out the lack of accountability even in cases where there was a monetary settlement. “The whole system has to be repaired,” he says. “An unholy alliance between the prosecutors and the police has to be repaired, and the power of police unions must be confronted. Qualified immunity has to be abolished.”

Roberts was formerly solicitor general of Antigua and Barbuda, and attorney general of the British Virgin Islands and Montserrat. The Caribbean countries have a direct interest in the cases brought to the commission: 30-year-old Shereese Francis, born in Jamaica, was suffocated in 2012 when four New York Police Dept. officers piled on her torso to handcuff her, causing her to go into cardiac arrest; and 26-year-old Botham Jean from St. Lucia died in 2018 after being shot twice in the chest while eating ice cream on his sofa by an officer who thought he had intruded into her Dallas apartment and not the other way around.

“There’s a recursive pattern of police violence that we must break, and unless it breaks the society cannot move forward together.”

— Professor Horace Campbell, Syracuse University

The officer was charged, tried and sentenced to 10 years but is appealing the verdict; a hearing has been set for April 27.

Roberts decried what he calls a pattern of dehumanization of the victims.

The last words of 17-year-old Vincent Truitt of Cobb County, Georgia, who was killed in 2020 by two bullets in the back, particularly haunt him. The boy cried out:

“Why did you shoot me?”

“That one really got to me,” says Roberts. “There was no rhyme or reason.”

Commissioner Niloufer Bhagwat of India also criticized police treatment of Black victims as less than human. In an email to Capital & Main, she wrote that in many cases “no questions were asked by police officials prior to the use of lethal force; neither was there an on the spot investigation or inquiry; within a few minutes and in some cases even a few seconds, innocent African Americans were shot dead by a hail of bullets.”

Roberts, who has served as a special rapporteur on the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, expects this commission’s report to reflect two central tenets of what has come to be known as “people-centered human rights” discourse, which he finds particularly relevant to this experience:

“Human rights are not granted by country or constitution,” he says. “They’re rights attached to us as human beings that don’t depend on color, race, creed: We are all human beings and as such we have basic human rights and we should be protected.

“Human rights trump sovereignty, so wherever human beings are being ill treated and brutalized, it is the business of the rest of us to see it and make it stop.”

Bhagwat says that now that the political and economic decline of the United States is visible, the international balance of power is changing. “The U.S. is no longer in a position to prevent the truth of the racist violence and atrocities against its own citizens from being known,” she says.

The commission’s report will include recommendations for the Biden administration and Congress that will address impunity.

“We’ve seen police actually do the right thing when dealing with mass shooters: calmly arrest them without breaking a fingernail on the person,” McLean says. “They know what to do; they just don’t want to do it when it comes to certain people. These police officers need to be routinely punished, and then they’ll be afraid to behave the way they behave.”

Copyright 2021 Capital & Main

-

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026Amid the Violent Minnesota Raids, ICE Arrests Over 100 Refugees, Ships Many to Texas

-

Featured VideoFebruary 4, 2026

Featured VideoFebruary 4, 2026Protesters Turn to Economic Disruption to Fight ICE

-

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 5, 2026

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 5, 2026Lawsuits Push Back on Trump’s Attack on Child Care

-

Column - California UncoveredFebruary 6, 2026

Column - California UncoveredFebruary 6, 2026What It’s Like On the Front Line as Health Care Cuts Start to Hit

-

The SlickFebruary 10, 2026

The SlickFebruary 10, 2026New Mexico Again Debates Greenhouse Gas Reductions as Snow Melts

-

Latest NewsFebruary 12, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 12, 2026Trump Administration ‘Wanted to Use Us as a Trophy,’ Says School Board Member Arrested Over Church Protest

-

Latest NewsFebruary 10, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 10, 2026Louisiana Bets Big on ‘Blue Ammonia.’ Communities Along Cancer Alley Brace for the Cost.

-

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 12, 2026

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 12, 2026They’re Organizing to Stop the Next Assault on Immigrant Families