Mike Kirakosyan spends his days working in the deep weeds of the health care system. He messages patients that it’s time to schedule their next visit for medications. He juggles calls and emails with providers to coordinate delivery of care. He helps patients fill out often complex medical forms, walks them through lab results, genially chases down those who’ve been away from the doctor for too long.

Kirakosyan, 33, does these things with a single goal in mind: to make sure the patients’ HIV viral loads become and remain undetectable, so low that the people cannot transmit the virus to others in the L.A. area — or beyond.

“This is very much a public health program as well as a patient care program,” says Kirakosyan, a registered nurse. “Making sure that patients are staying healthy, staying undetectable, reduces the rates of transmission in the community.”

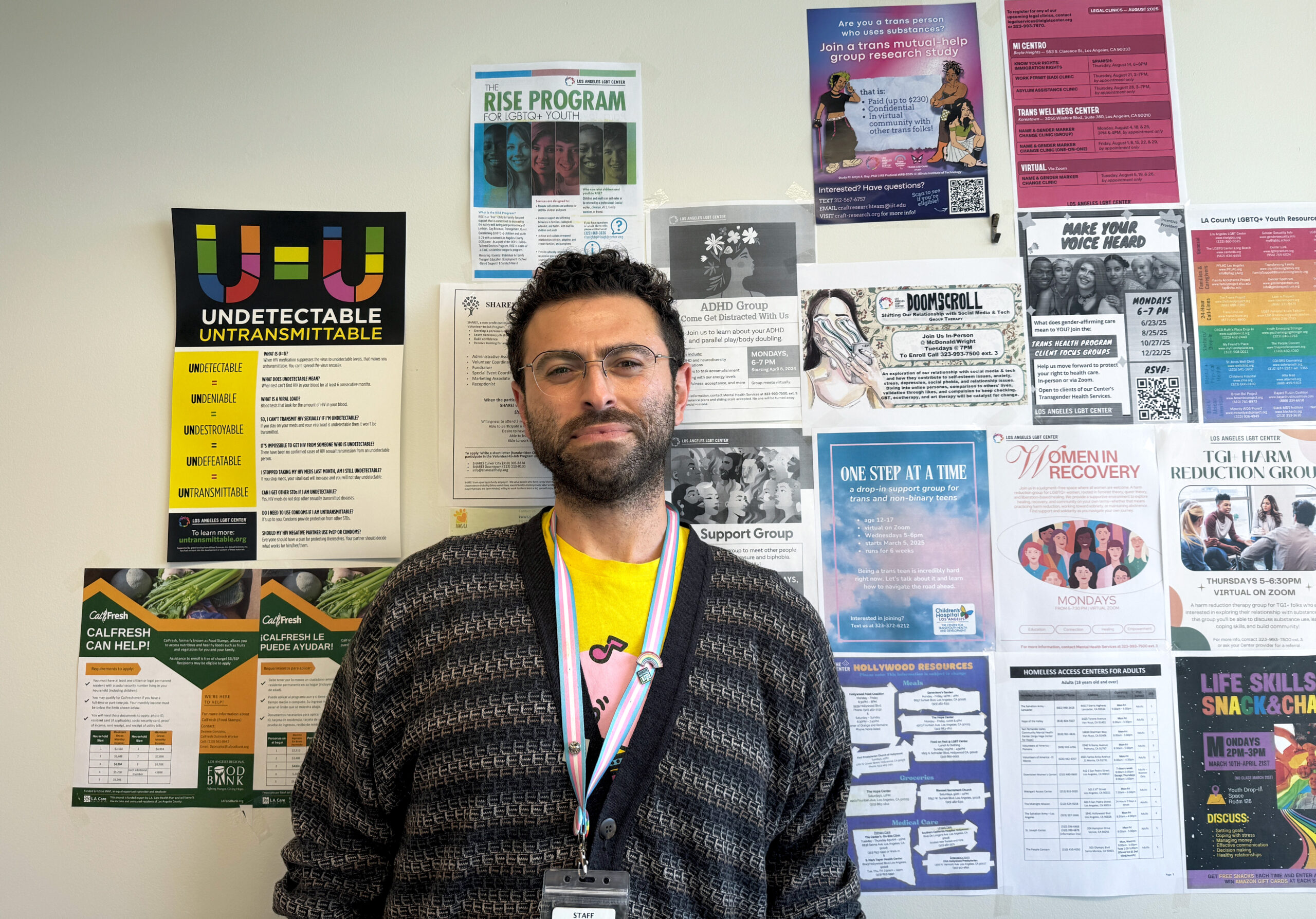

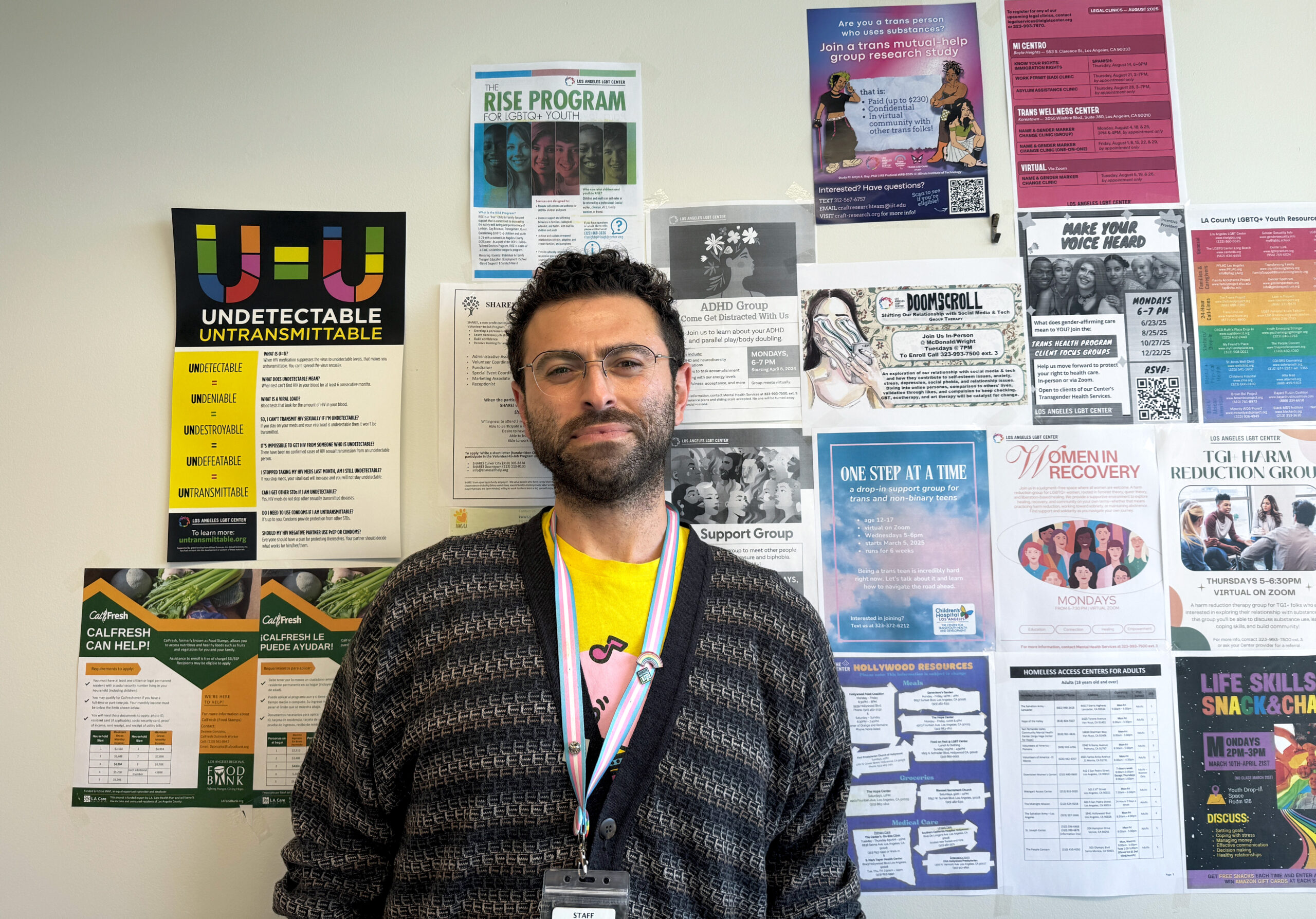

Mike Kirakosyan at the Los Angeles LGBT Center.

It is not a one-person job. Kirakosyan works as part of the Medical Care Coordination team at the Los Angeles LGBT Center, one of several such MCC programs in the area administered through the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health. The MCC program has long been recognized for helping decrease infection rates in L.A. County, increasing quality-of-life years for those living with HIV and remaining cost efficient in the process.

In other words, it’s a success story. It is also facing the most severe strain it has been under since its inception in 2013. The Trump administration’s gutting of federal funding is compromising the county’s ability to run the program at its current scale, leaving the team understaffed and desperately trying to handle ever-greater work loads. Kirakosyan worries for his fellow workers and for himself — but mostly, he worries for his patients.

“These policy changes are murder. I don’t know how else to describe it,” Kirakosyan said. “Patients are going to fall through the cracks. It’s been really discouraging — heartbreaking.”

* * *

Each Medical Care Coordination team consists of a care manager (Kirakosyan’s job), a medical social worker and a licensed vocational nurse. In addition, MCC programs employ retention specialists to help keep patients enrolled.

To Kirakosyan, the team concept works beautifully — and busily. At the L.A. LGBT Center, the MCC program started this year with six such teams of workers, with each team responsible for roughly 1,000 HIV patients.

“Obviously, not all of our patients are high acuity (with severe medical issues),” Kirakosyan said. “But it’s a lot of patients, a lot of messages and calls. Our teams work so well together that it all somehow works.”

But that was before a series of budget shocks rocked the system. In January, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services abruptly stopped its practice of announcing a key AIDS/HIV prevention grant award to the county in a single annual sum. Instead, federal officials began issuing what county officials called “episodic partial notices” of funding through the Ryan White HIV/AIDS program — leaving administrators in the county’s Public Health Division of HIV and STD Programs unsure what a year’s worth of funding would ultimately be.

That chaos was compounded by the end of temporary funding increases from an HIV-directed initiative. That program is administered through the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, a target for severe budget and staffing reductions by Trump’s administration. One-time post-pandemic recovery funds from L.A. County were also depleted.

Then came a second shock: Trump was proposing to eliminate the federal Health Resources and Services Administration, a little known agency that nevertheless awarded more than $12 billion in grants in 2024 to support community health centers and programs, including HIV/AIDS treatment and prevention.

Critically, the HRSA’s workers help manage the myriad projects that fund such endeavors. KFF Health News reported that more than 700 of the agency’s 2,700 employees had left or been fired between February and June. Such a loss of workforce meant the agency would struggle to handle funding requests or distribute money in a timely manner.

In an email, the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health told Capital & Main that it cut staff in its HIV and STD program in response to the budget uncertainty, eliminating 38 contract workers and reassigning 36 full-time employees elsewhere. Ultimately, county officials decided to reduce HIV care and treatment contracts by 30%, which the email described as “fiscally prudent.”

The fallout was swift. The Los Angeles LGBT Center eliminated one of its MCC teams in late spring, meaning that roughly 1,000 patients would have to be absorbed by the remaining five. In August, a second team was eliminated.

* * *

Now, Kirakosyan says, those in the Medical Care Coordination program are taking on dramatically heavier numbers of patients and seeing increased workloads. They’re also looking over their shoulders. “I see myself next on the chopping block,” Kirakosyan said. Some of his co-workers, sensing the same, have begun looking for other jobs.

His primary concern, though, remains his patients — the ones with whom he already works on a regular basis, but also new patients coming his way as the result of the LBGT Center’s reduction in staff.

“The whole point of our program is that there are people who have a really hard time navigating our diseased health care system,” Kirakosyan said. “We help with all that. We also have a medical social worker on every care team, and they provide wraparound services — assisting with housing, food, transportation, things like that. That’s the kind of work that is going to be extremely difficult to pick up the slack for.”

As a result, he says, patients are going to go underserved. Their absences from treatment plans will get noticed later than they should. Retention of patients is likely to suffer. And importantly, Kirakosyan says, his and his co-workers’ ability to develop rapport with the patients is going to become strained by the sheer demands of time.

The Los Angeles LGBT Center is under fire from every direction when it comes to funding, including federal Medicaid cuts and California’s own budget crisis. “They can’t just make up the funding that we are losing for MCC,” Kirakosyan said. So the program loses funding, and people.

“There’s an injectible HIV medicine that we have a lot of patients on,” the nurse said. “It’s generally given every two months. And lately I’ve noticed that patients have been falling through the cracks. We try to reach out to every patient when it’s time to schedule their next injection, but with fewer people to make calls, patients are falling through. They’re missing their injections, and some have to start over with the entire program.

“That means that more people will be out there with an active viral load,” Kirakosyan added. “It raises the risk of transmissions within the community. Having sex is about to get a lot more dangerous than it is right now, and a lot of our patients are scared about what’s going to happen in the future. It’s hard to even know what to tell them.”

Copyright 2025 Capital & Main

The SlickJanuary 12, 2026

The SlickJanuary 12, 2026

Latest NewsJanuary 13, 2026

Latest NewsJanuary 13, 2026

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 22, 2026

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 22, 2026

Column - California UncoveredJanuary 14, 2026

Column - California UncoveredJanuary 14, 2026

Latest NewsJanuary 16, 2026

Latest NewsJanuary 16, 2026

The SlickJanuary 20, 2026

The SlickJanuary 20, 2026

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 15, 2026

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 15, 2026

Latest NewsJanuary 21, 2026

Latest NewsJanuary 21, 2026