Immigration officials in Minnesota arrested more than 100 refugees and sent many of them to Texas detention centers where they faced long interviews to once again prove they qualified for protection when the U.S. resettled them.

Thanks to a judge’s order, the federal government must now release them.

“Families in Minnesota are eagerly awaiting the return of their loved ones,” said Stephanie Gee, senior director of U.S. legal services with the International Refugee Assistance Project, a resettlement agency that brought the class action lawsuit.

“It’s a big victory for us, and a huge relief for everyone involved.”

She noted that the organization is watching to see if the Trump administration complies with the judge’s order. The judge gave the administration five days to release those covered by the lawsuit, making the deadline Feb. 3.

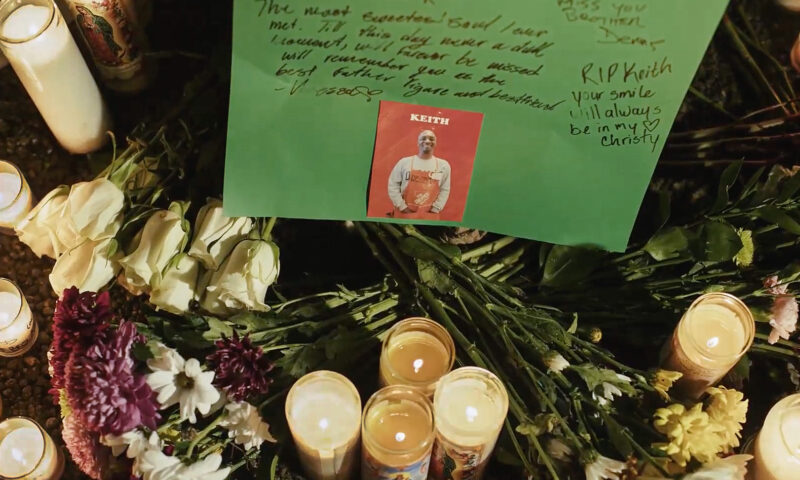

In early January, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services announced Operation PARRIS to reexamine refugee claims of people recently resettled in Minnesota, saying that the agency was looking for cases of fraud. The decision came as protests escalated in Minnesota over immigration officials’ presence — and their killing of two U.S. citizens, Renee Good and Alex Pretti.

Last week, a federal judge ordered the Trump administration to stop detaining refugees resettled in the state, issuing a temporary restraining order less than a week after a refugee resettlement agency filed a class action lawsuit. The judge also ordered Immigration and Customs Enforcement to release those it had detained.

District Judge John R. Tunheim said the program marked a “stark shift” in the government’s treatment of refugees.

“The stories of terror and trauma recounted by Named Plaintiffs in their Amended Petition make this harm impossible to ignore,” Tunheim wrote in the order temporarily blocking the operation.

The departments of Homeland Security and Justice did not respond to requests for comment from Capital & Main. ICE also did not respond.

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services responded via email, quoting its own press release about the launch of the operation in saying that Minnesota is “ground zero for the war on fraud.”

The agency did not respond to questions about evidence of fraud and did not provide any evidence or examples in its press release.

Gee said that because refugees have already lived through terrifying ordeals — in many cases wrongful detention or torture at the hands of their government in their homelands — the sudden arrests have been intensely retraumatizing.

“The U.S. government made promises to them when they resettled them as refugees. The whole point of processing them through that program was to provide permanent safety and stability,” Gee said. “To see this exact population be treated this way has been really horrific.”

U.S. law defines a refugee as someone who fled their country because of persecution based on race, nationality, religion, political opinion or membership in a social group, such as the LGBTQ+ community. They wait in third countries to be screened and vetted through a process that often takes years. U.S. officials screen those who end up getting resettled in the United States.

Once approved, they fly to the U.S. using interest-free loans from the government, and refugee resettlement agencies receive them and help them get to know their new homes. The U.S. government provides short-term stipends to help them get on their feet.

Upon arrival, they are immediately eligible to work and they have visas allowing them to be in the U.S., but they must wait one year to apply for permanent residency, or green cards.

Under Operation PARRIS, immigration officials targeted refugees who had not yet received their green cards. According to a court document filed in the lawsuit, President Donald Trump’s travel ban froze green card processing for many of the refugees targeted by the operation.

Gee said some of those arrested appeared to have been targeted in their homes or through “call in letters” that ask the refugees to go to appointments at ICE offices while others seemed to have been racially profiled on the streets in Minnesota.

Many were taken to Camp East Montana at Fort Bliss in Texas, where three people have died in the span of six weeks, before ICE transferred the refugees to a detention facility in Houston, Gee said.

The arrested refugees are from across the globe, Gee said, and among them are many from Minnesota’s Somali community, which has faced particular targeting by Trump. The complaint filed on behalf of the refugees in court offered examples of Trump’s “racialized smears” of Somali and Somali American Minnesotans, including when he referred to them collectively as “garbage.”

The complaint called the operation’s detention of refugees “a Kafakaesque deprivation of their liberty.”

“They have been forced to endure the indignities of being handcuffed and shackled in chains for prolonged periods, causing unnecessary physical pain,” the complaint says. “In detention, they are exposed to harsh conditions and provided no information about why they are being detained or when they will be released.”

According to court documents, one of the plaintiffs, identified as D. Doe, was at home when someone knocked at the door and told him they believed they had struck his car. They described the wrong car, and he told them they were mistaken. They came back and described his car, and when he stepped outside, armed men arrested him.

His wife, identified as M. Doe, begged the officials not to take her husband and tried to show them the couple’s refugee paperwork, but they took him anyway, the complaint says.

Officials sent him in shackles to a detention center in Houston, where officials interrogated him about his refugee case, court records say. Eventually, ICE released him and several others from custody without their documents, and they had to figure out how to get back to Minnesota from Houston.

Even though D. Doe has returned home, his wife still lives in fear.

“She wakes up in the middle of the night in fear and barricades her home in case officers return to arrest her or her family,” the complaint says.

According to court records, another of the named plaintiffs, identified as U.H.A., a refugee who came to the U.S. in 2024, was on his way to work when immigration officials detained him. Even though he was complying with the officials, the document says, they threatened to shoot him if he ran away.

“The officers proceeded to taunt him by telling him not to worry, that he would go home soon — to the country he had fled as a refugee,” the complaint says.

In custody in Texas, he had to sleep on the floor, the document says. Then, ICE flew him back to Minnesota. As of last week, he was still in custody.

His younger brother, identified in court documents as K.A., was driving behind him and has since been so scared by the ordeal that he has not returned home to sleep, choosing instead to sleep where he works. He also hasn’t gone to school or even to the grocery store, court documents say.

As of now, both the program and the lawsuit are specific to Minnesota, but Gee said her organization is concerned that the operation could spread to other states as well. She said she is also worried that the administration will continue to try to target refugees in other ways, even if it can’t detain them.

The judge will hold a hearing on a potential permanent block on the refugee detention program in mid-February.

Copyright 2026 Capital & Main

Latest NewsJanuary 8, 2026

Latest NewsJanuary 8, 2026

The SlickJanuary 12, 2026

The SlickJanuary 12, 2026

Pain & ProfitJanuary 7, 2026

Pain & ProfitJanuary 7, 2026

Latest NewsJanuary 6, 2026

Latest NewsJanuary 6, 2026

Latest NewsJanuary 13, 2026

Latest NewsJanuary 13, 2026

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 8, 2026

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 8, 2026

Column - California UncoveredJanuary 14, 2026

Column - California UncoveredJanuary 14, 2026

Latest NewsJanuary 16, 2026

Latest NewsJanuary 16, 2026