The 16 months between the broadcast of home video of the brutal beating of Rodney King by Los Angeles Police Department officers and the resignation of Chief Daryl Gates were marked by gripping tension that broke in the turbulence of the 1992 riots. Calls for Gates’ removal came from across the political left and center of Los Angeles. Voices included Mayor Tom Bradley, a cautious insider; loyal Democrat and future U.S. Secretary of State Warren Christopher; Police Commissioner Stanley Sheinbaum; U.S. Rep. Maxine Waters; and a variety of activists.

As chair of the ACLU Foundation of Southern California from 1987 to 1994, Danny Goldberg had a front-row seat as that coalition put aside its ideological differences to force Gates out.

As chair of the ACLU Foundation of Southern California from 1987 to 1994, Danny Goldberg had a front-row seat as that coalition put aside its ideological differences to force Gates out.

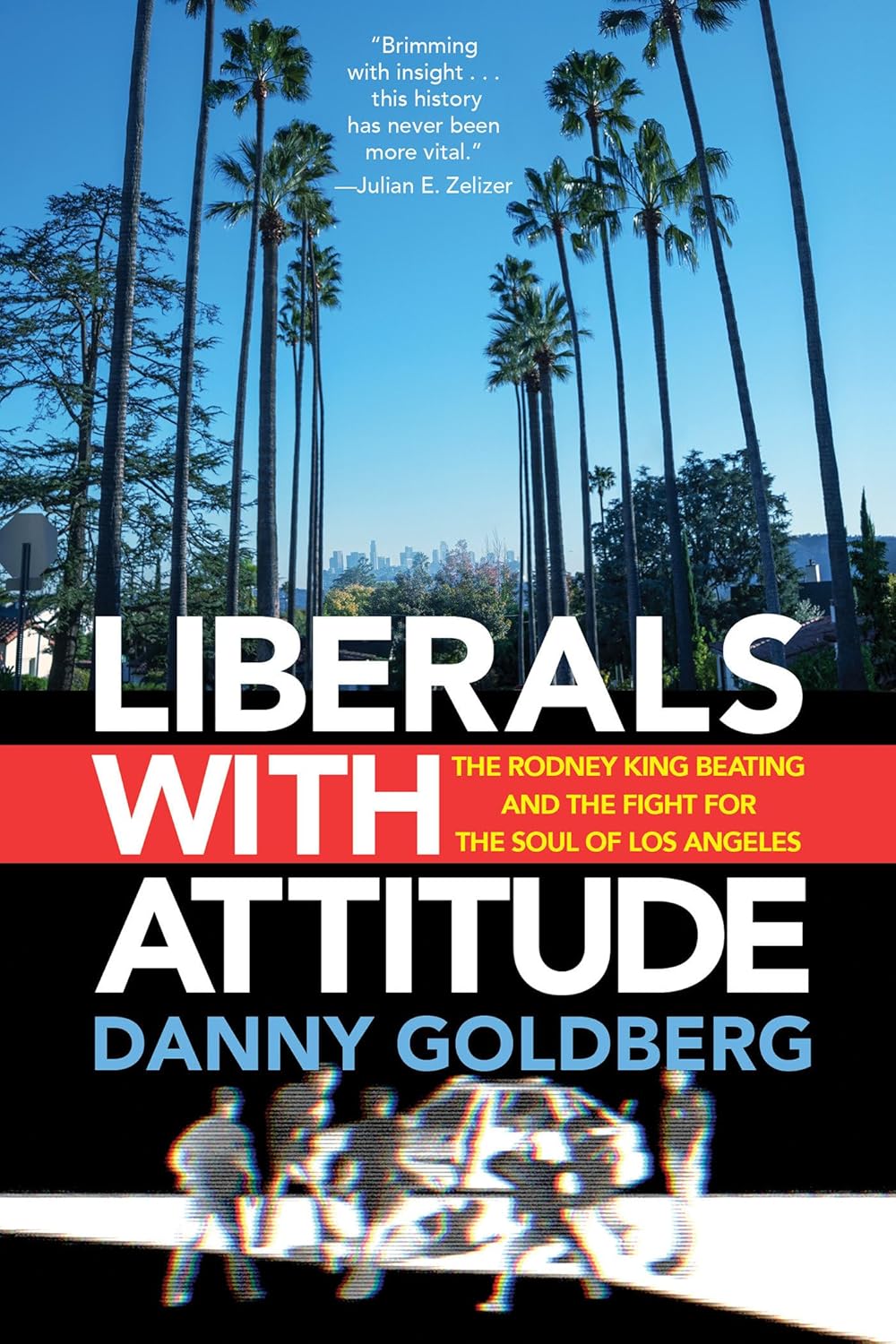

In his latest book, Liberals with Attitude: The Rodney King Beating and the Fight for the Soul of Los Angeles, Goldberg chronicles the ultimately successful effort to make Gates step down and reform the city’s charter to prevent the rise of another chief accountable to no one. Capital & Main spoke with Goldberg about how the lessons of L.A.’s past may serve as a guide at a time when President Donald Trump has been rapidly consolidating power.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Capital & Main: The Los Angeles City Charter in the early 1990s was instrumental in keeping Gates in place. Can you explain how that worked?

Danny Goldberg: At some point in the late 1930s, there was a reform movement in L.A. that was a reaction to corruption in City Hall. And the city charter was amended at that time to make the Los Angeles Police Department virtually autonomous of the rest of city government. It made it virtually impossible to fire the police chief. Certainly the mayor had no authority to do so. And it created a series of obstacles that made it virtually a job for life. And part of the struggle in the city after the Rodney King beating was to amend that city charter to create the same kind of accountability that police departments have in other cities.

In our current political moment, the Trump administration is dismantling government structure and concentrating power in the president under the so-called unitary executive theory. Coalition building between centrists and leftist Democrats with help from local media drove the engine to remove Gates. Is there a similar strategy to be employed with Trump?

Well, obviously, there are many, many differences between a national situation in 2025, ’26, and a basically local situation in L.A. in the early ’90s. The technology is different, politics are different, the nature of the respective offices are different. The echo that to me is very vivid between the period I write about and now is how public opinion works relative to crime, fear of crime, and how that can be exploited to the detriment of racial minorities and how to overcome that fear on the part of progressive leaders.

Tom Hayden said that movements succeed when they can persuade moderate Machiavellians. And Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. similarly said the biggest obstacle to progress was what he called moderate whites who basically looked the other way. So the challenge today is the same as what I write about in the sense of: In order to oppose racist authoritarian impulses, there needs to be a coalition between the movements and the moderates. And those are the lessons that I think are applicable, because public opinion still matters. It’s never been a real democracy. It’s certainly not a real democracy now, but public opinion still has power.

Are there any parallels to be drawn between the brutality shown by federal agents against Latinos under the guise of immigration enforcement and the violence that we’ve seen from the LAPD, specifically what you’re writing about in your book? Many of the tactics that we are seeing used on the immigrant community were pioneered by policing agencies in L.A. and have been in use by those agencies for decades.

There’s no question that the LAPD during the era when Daryl Gates was the chief was the leader in militarization of policing. They had the most helicopters. They had military hardware that they used as battering rams to break into houses where they said there was drug dealing. Sometimes there was, often there wasn’t. And that consciousness of the war on drugs and the dehumanizing of large sections of the population certainly is consistent with dehumanizing immigrants to some part of the society.

The problem wasn’t all LAPD officers. The problem was that there was this code of silence that protected that 1%. When Rodney King was beaten, there were four officers that beat him with metal batons. But 20 other police officers were there too. I bet that there are people who got into ICE thinking it was a good job and a good paycheck, and who’ve had second thoughts about the morality of what they’re doing but are scared to speak up.

Many of the characters challenging Gates in your book are today playing roles where they are maintaining the status quo. Karen Bass, for example, came from a leftist organizing tradition and was vocally critical of police. But as mayor, her policies have included hiring more police officers and paying them more overtime in spite of a looming budget crisis. What do you make of that shift?

The mayor of Los Angeles has limited power. You know, unlike in New York, where the mayor has greater institutional power, the power by design is diffused between the City Council and the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors. And you know, maybe I’m just overly sentimental. I still give Karen Bass a lot of the benefit of the doubt. I think it’s a very difficult job. I think that hiring police officers is not automatically a bad thing. The problem is, what do they do with their power?

Daryl Gates left the LAPD, but police brutality has continued. And the number of people killed by police nationwide has risen each year since the murder of George Floyd. Do you think that the effort to brand Gates as the face of LAPD violence was a mistake?

You raised a point that really haunted me when I was writing the book, which is, “Did it actually make any difference to get rid of him?” It certainly made a difference at least where you didn’t have the leader publicly saying things that were racist. And they did get rid of some of the most brutal officers. It wasn’t a revolution, it wasn’t a panacea, and there’s still tremendous problems. I do think it made things better. And I think making things better is better than making them worse. It’s hard to fix everything all at once. I think it was incremental progress that’s worth celebrating, because it’s a rare example of any kind of a reform after police violence. Let’s not forget, after George Floyd was murdered, nothing changed nationally. The political system resisted any reform.

What was the biggest lesson that you would want organizers, in this moment of the Trump administration, to learn from what you’ve written about?

I think the main lesson is that people in the center and the left have to work together. It’s worth looking at the specific group of people that came together to reform the LAPD because it was a very wide range ideologically. For example, Mayor Tom Bradley and Maxine Waters were not crazy about each other. Warren Christopher was the epitome of the establishment Democrat. Stanley Sheinbaum was a lefty. But they found common cause in reforming the LAPD.

Let’s be realistic. We know people on the center and the left usually don’t like each other very much. They don’t go to the same parties, they don’t support the same candidates, they have different views of life. But if you’re against fascism, you’ve got to find ways of focusing on specific issues and working with people who you otherwise don’t really like very much.

Copyright 2025 Capital & Main

Latest NewsJanuary 8, 2026

Latest NewsJanuary 8, 2026

The SlickJanuary 12, 2026

The SlickJanuary 12, 2026

Pain & ProfitJanuary 7, 2026

Pain & ProfitJanuary 7, 2026

Latest NewsJanuary 6, 2026

Latest NewsJanuary 6, 2026

Latest NewsJanuary 13, 2026

Latest NewsJanuary 13, 2026

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 8, 2026

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 8, 2026

Column - California UncoveredJanuary 14, 2026

Column - California UncoveredJanuary 14, 2026

Latest NewsJanuary 16, 2026

Latest NewsJanuary 16, 2026

As chair of the ACLU Foundation of Southern California from 1987 to 1994, Danny Goldberg had a front-row seat as that coalition put aside its ideological differences to force Gates out.

As chair of the ACLU Foundation of Southern California from 1987 to 1994, Danny Goldberg had a front-row seat as that coalition put aside its ideological differences to force Gates out.