For the past six months, Pastors LaKeith and Jerice Kenebrew have been reporting to work at Hillside Tabernacle Church, one of 11 houses of worship damaged or destroyed in the Eaton fire.

The blaze, which erupted late on Jan. 7, spread quickly — engulfing nearby homes and businesses in Altadena, a foothill community of Los Angeles’ San Gabriel Mountains.

Now, on any given day, the Kenebrews juggle visits to the church from workers and contractors while navigating the long process of rebuilding their home, one of more than 9,000 structures destroyed in the fire.

The Kenebrews’ ability to minister to their congregation is now limited. Before the fire, the couple held community events and multiple services a week at the church. Now, only Sunday services remain — and those are livestreamed from a rented studio tucked in an industrial park in Duarte, a city located about 12 miles east of their damaged church. Congregants who are fire survivors are now scattered throughout the county.

Pastor LaKeith Kenebrew delivers a sermon to congregants of the Hillside Tabernacle Church at a rented studio in Duarte in July.

Lu Jones holds her Bible during a Hillside Tabernacle Church service in Duarte.

From offices inside a church that lacks power and an internet connection, Jerice Kenebrew calls members of the congregation individually and posts encouraging affirmations on the church’s Facebook page. “I let them know that we’re here. They can call any time,” she said.

But on Sunday afternoons in their rented studio, their week takes a joyful turn as congregants clap, sway and pray through a service, enlivened by a percussionist, two synthesizers and Jerice Kenebrew’s powerful singing voice. Near the end of a June service, LaKeith Kenebrew, dressed in a white tunic, pointed congregants to legal and recovery resources — then returned to a message of resilience. “We have been devastated,” he said, “but God has given grace to us.”

The Kenebrews are fighting to keep a community of more than 150 congregants together after the January wildfires, which destroyed the home they shared with their 24-year-old son and displaced Jerice Kenebrew’s parents, who also lost their Altadena home in the fire.

This family’s story of loss is repeated across the region, with tens of thousands of homes destroyed in the Eaton fire and the Palisades fire, which erupted along the coast on the same day. For Black families like the Kenebrews, the disaster also threatens a deep-rooted presence in Altadena and raises questions about the future of a historically Black community in Southern California.

Pastor Jerice Kenebrew, center, speaks to members of the congregation following Sunday service.

Frances Harris, Jerice Kenebrew’s 76-year-old mother, is an elegant woman with a quiet, dignified presence. It is through her parents that the idea for this church was born. Hillside Tabernacle initially opened in a storefront just up the street in 1967. In the late 1980s, the church moved into its current building — a former post office on Fair Oaks Boulevard, sold off by private owners as Black families moved in and white residents left. Frances Harris remembers the sellers calling the area “ghetto.”

In 1999, Frances and her husband Jerry Harris took over leadership of the church. Like his wife, Jerry Harris had deep roots in the community. He attended Pasadena public schools, including John Muir High School, baseball legend Jackie Robinson’s alma mater. Jerry Harris would later become the Pasadena Department of Water and Power’s first Black cable splicer, a job that involves installing high voltage electrical cables underground. Their four-bedroom house became a gathering place for the family.

Despite all they had built, the Harrises had no insurance when their home burned in January. They blame their mortgage servicer for failing to pay their premium after being forced onto the California FAIR Plan, the state’s so-called insurer of last resort. Their original insurer had dropped them months earlier due to fire risk. The Harrises are suing their mortgage servicer, as well as Southern California Edison, whose equipment may have sparked the blaze.

In early July, six months after the fire, 70% of survivors reported their claims had been delayed, denied or underpaid. For the Harrises, navigating the Federal Emergency Management Agency was an ordeal. “We went to the office at least 20 or 30 times,” Frances said. “I got sciatica from the stress.”

And the family is still coping with the trauma caused by the fire itself. Like about a dozen members of the congregation, Jerry Harris is a veteran. “Just driving through the area will trigger him because it looks like a war zone,” LaKeith Kenebrew said of his father-in-law, who saw combat in Vietnam.

Frances and Jerry Harris stand in the lot of their burned home in Altadena.

Jerice Kenebrew remembers the night of Jan. 7 vividly. “Everything was just red and orange,” she said. She and her husband spent the night driving back and forth into the fire zone in spite of the hurricane force winds, as they tried to save their church. It wasn’t until a week later that she began to question their actions. “I said, what were we thinking, putting our lives at risk so many times?” Jerice Kenebrew remembered.

Their persistence — they visited the church seven times over the course of the night — helped save the structure. “I think the last time we came, the roof was on fire,” Jerice Kenebrew said. “We saw smoke coming out, and we tried to flag down three different fire trucks. Finally, we just jumped in the middle of the street in front of a fire truck and made them stop,” she added.

Jerice Kenebrew stood outside her damaged church where signs of destruction surrounded her: the charred remains of the community center once connected to the church, empty lots recently cleared by the Army Corps of Engineers, a liquor store and grocery down the street reduced to rubble. Across the way, a row of duplexes that had housed church members stood as a scorched shell. Some days, she said, she can’t stop crying.

Their son David was safely away from the fire, but still endured a harrowing night. Around 3:30 a.m., his Alexa app began pinging — alerting him to breaking glass as flames consumed the family’s home, less than a mile from the church. From the safety of a friend’s house, he tried frantically to reach his parents, but fire-damaged cell towers made contact impossible. “I think the initial impact really scared him,” Jerice Kenebrew said. “He realized he could have lost his parents that night.”

The Kenebrews’ house and their church are both west of North Lake Avenue in Altadena — a historic redlining boundary that decades ago barred Black residents from buying homes east of the line. The line also gained tragic significance during the fire. While thousands of those living east of the line received evacuation notifications before midnight, Altadena residents living west of the North Lake Avenue did not receive those warnings until 3:25 a.m., four hours after the first reports of fires in the area.

About seven months after the disaster, the reasons behind the failure of Los Angeles County’s electronic alert system remain unclear. In May, Supervisor Kathryn Barger told the Los Angeles Times that it stemmed from a “breakdown in the communication” among county fire, sheriff and emergency management officials — agencies that were jointly responsible for issuing evacuation alerts.

But more recently, the supervisor’s views have evolved, according to Helen Chavez Garcia, her spokesperson. As Barger heard firsthand accounts from members of the command post, she grew less certain that officials could have accurately anticipated the fire’s path. “The ambient weather conditions were just awful,” Chavez Garcia said, adding that the conditions made it difficult to gauge “the directionality of those embers.” She said fuller answers are expected in a quarterly report by an outside consultant that is to be published in late October.

The altar of the fire-damaged Hillside Tabernacle Church now serves as storage for supplies to be distributed to community members in need.

LaKeith Kenebrew radiates warmth both from the pulpit and in the quieter surroundings of his office. But his voice takes on a detectable edge when he describes what he sees as disparate treatment of the heavily Black and Latino parts of Altadena and the more affluent and more heavily white neighborhoods to the East, both during the fire and in its aftermath. “We received a warning to get out [at the time] that my son’s Alexa was saying windows are breaking at your house, which literally means that my house was burning down at the time they were telling us” that the fire was approaching, he said.

Large swaths of West Altadena burned in the Eaton fire, and all but one of the 19 deaths associated with the fire occurred in the heavily Black and Latino neighborhoods west of Lake — which was also the last to burn in the regionwide firestorm. A Los Angeles Times investigation found that the Los Angeles County Fire Department had just one county fire truck in West Altadena at 3:08 a.m. on Jan. 8. The county’s fire chief, Anthony C. Marrone, defended his department’s response in a video shown at a virtual community meeting in late July, saying that the article relied on data that presented an incomplete picture of the number of fire trucks in the area at the time.

In April, sitting in his office, LaKeith Kenebrew praised elected officials — from the state’s governor to congressional leaders to Barger — who he said are helping the community and the church get the support they need. But in early June, he also said he sees an imbalance in how the rebuilding is playing out.

“There’s just a difference,” he said. “Who gets taken care of first? Who has the opportunity to have removal services? Who is still in hotel rooms and fighting to get FEMA and SBA [Small Business Administration] loans, you know, versus those who are already through the process?”

Among the displaced is Robert Sanders, a 72-year-old retiree. In July, he arrived at the rented Duarte studio in a gray pinstripe suit — church ready, despite having spent the night in his 2009 Infiniti.

Six months after the fire, his savings were gone. He was splitting nights between a hotel room in Ontario and his car. FEMA paid for four months of hotel stays before that money ran out, Sanders said. LaKeith Kenebrew helped connect him to a donor who gave him $5,000 — money that vanished quickly after he started paying for his own hotel room.

LaKeith Kenebrew’s sermon that day had ended in a fiery invocation, which he delivered as he stepped away from the podium and moved among those assembled. He urged the congregation to push back against “brokenness of heart, brokenness of spirit, financial oppression — all of those things fighting against you,” with the help of a God he called upon to “destroy every yoke.”

Asked what had inspired him most that day, Sanders replied, “Most everything the pastor said lifted me up,” adding, “The church is my life.”

Robert Sanders passes the collection plate to Jerry and Frances Harris.

But attending church has now become harder. In mid-July, Sanders moved to an apartment in Moreno Valley, 60 miles away. He is not alone in leaving the community. Many Altadena homeowners are selling their parcels, although sales have slowed in recent months as prices have declined. Sanders said he knows 25 or 30 people displaced by the fire. He estimates that only half will return to Altadena.

Jerice Kenebrew said in a text that about 30 members of their congregation saw their homes damaged or destroyed by the fires. The Kenebrews are meeting the needs of their scattered congregation by strengthening the church’s online presence, which they initiated during the COVID pandemic. Now “it’s just fine-tuning,” she said.

The Kenebrews and the Harrises remain fortified by their close family ties. The Harrises are now living with a son in Pomona, while the Kenebrews rent an apartment in Monrovia, a 20-minute drive from their church. Still, they gather for dinner every Monday and try to stay attuned to each other’s emotional needs. Jerice Kenebrew is careful not to crowd her parents as they navigate the rebuilding process.

“I’m thankful they’re not bossy,” said Harris, who was sitting nearby. “But they know that if I need them, they’re there. Once in a while, they give a strong opinion, and if I want to reply I will,” she added. “If I get quiet, they know.”

And, there are physical signs of progress. A temporary home — an accessory dwelling unit — is taking shape on the Harrises’ lot. They plan to live there until their home is rebuilt.

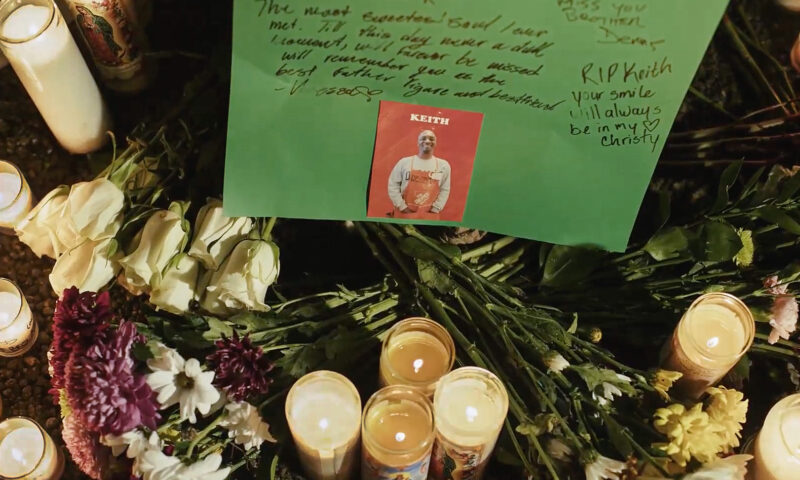

In late July, Hillside Tabernacle Church hosted a service in its parking lot that marked the six-month anniversary of the fire. Over 50 people gathered on folding chairs beneath a canopy tent, including at least 10 church leaders from the fire-affected communities of Altadena and Pasadena. The speakers touched on themes of resilience, community and the centrality of prayer.

Community members gather for an interfaith prayer service commemorating the six-month anniversary of the Eaton fire.

After the service, Kenebrew pointed to more signs of progress. “We’ve had the carpet replaced. We had the drywall replaced. The inside is almost ready,” he said of the building. The Kenebrews anticipate Hillside Tabernacle will reopen as early as September.

Getting their congregants to return is another matter.

The fire halted many of the church’s community outreach efforts — Meals on Wheels, expungement clinics and more. (A shiny new van is serving as a mobile ministry, collecting and distributing supplies to fire survivors.) Some residents are still coping with PTSD from the night of the fire and are reluctant to return to Altadena. Those who had moved away before the fires are even less inclined to come back, said LaKeith Kenebrew.

Jerice Kenebrew does not view the future through rose colored glasses. For some in the community, “The life that they had, it’s not going to return or even be better,” she said. But on that day, in the church parking lot, there were signs of resilience.

After the prayer vigil, local faith leaders — members of the Pasadena-based Clergy Community Coalition, which sponsored the event — lined up for a photo in the Hillside Tabernacle’s parking lot. Some had lost their churches, others ministered to grieving congregations. Still, they smiled brightly for the camera.

The shared trauma, said Jerice Kenebrew, had strengthened the Hillside Tabernacle’s bond with the community it serves. That, she said, is “a bright shining star.”

Copyright 2025 Capital & Main.

All photos by Barbara Davidson.

Latest NewsJanuary 8, 2026

Latest NewsJanuary 8, 2026

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 1, 2026

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 1, 2026

The SlickJanuary 12, 2026

The SlickJanuary 12, 2026

Pain & ProfitJanuary 7, 2026

Pain & ProfitJanuary 7, 2026

Latest NewsJanuary 6, 2026

Latest NewsJanuary 6, 2026

Latest NewsJanuary 13, 2026

Latest NewsJanuary 13, 2026

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 8, 2026

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 8, 2026

Column - California UncoveredJanuary 14, 2026

Column - California UncoveredJanuary 14, 2026