Education

Reporting on Hunger in Schools: Let Them Eat “Balance”

Even as the new documentary A Place at the Table highlights in heart-wrenching fashion the plight of 16 million U.S. children who don’t know where their next meal is coming from, some want to end a safety net that for decades has stood between some kids and a slow death from malnutrition – the school meal program. Think starvation can’t happen here, in one of the richest countries on earth? Think again. Not only could U.S. children starve without school meals, but not all that long ago, they did.

Terence Jeffrey, editor in chief of CNSnews.com, argues in an article entitled “Sixty-four Percent of Schoolchildren Fed on Federal Subsidies” that the federal school lunch program is “a weapon liberals employ in their war against the family.” This bizarre idea is based on data he presents which allegedly show a correlation between the increasing number of children eating government subsidized school meals since 1969, and the increasing number of U.S. babies born out of wedlock in the same time period.

Putting aside for a moment the obvious flaw in this reasoning – that correlation does not equal causation – let’s instead focus on the numbers. CNSnews.com bills itself as “a news source for individuals, news organizations and broadcasters who put a higher premium on balance than spin and seek news that’s ignored or under-reported as a result of media bias by omission” (emphasis mine).

This dedication to “balance” makes it hard to fathom why Jeffrey omits vital information which would have helped explicate the numbers he cites.

Since 1946, when the National School Lunch Program began, some students have always paid for their meals, while others have received a free lunch at government expense.

Jeffrey tells us that in the 1968-69 school year, while 19.5 million kids ate a daily school lunch, only about 2.9 million (about one in 6.7) were getting their lunch for free. By 2011-12, 18.7 million of the 31.5 million school cafeteria patrons ate free (about one in 1.7). So yes, more students in school cafeterias today are eating free meals than in 1968-69.

However, Jeffrey neglects to mention that in 1968-69, the National School Lunch Program operated very differently than it does today. In the late 1960s, most Americans believed that there was no hunger in this country, and although some children in some schools were able to get a free lunch, most children in poverty were shut out of the school meal program. In the interest of promoting “balance” over “spin,” let’s take a closer look at that era.

In 1967, a team of doctors did a study of hunger in the Mississippi Delta that shocked the nation when it reported that “We saw homes with children who are lucky to eat one meal a day…We saw children who don’t get to drink milk, don’t get to eat fruit, green vegetables, or meat.…Their parents may be declared ineligible for the food stamp program, even though they have literally nothing.…We do not want to quibble over words, but “malnutrition” is not quite what we found.…They are suffering from hunger and disease and directly or indirectly they are dying from them—which is exactly what “starvation” means.”

A report by the Committee on School Lunch Participation published as Their Daily Bread in April 1968, and quoted on the USDA’s [U.S. Department of Agriculture] Web site, highlighted the fact that, at that time, “whether or not a child is eligible for a free lunch is determined not by any universally accepted formula, but by local decisions about administration and financing which may or may not have anything to do with the need of the individual child. And generally speaking, the greater the need of children from a poor neighborhood, the less the community is able to meet it.”

The report went on to say that “The net result is that the children in the neediest areas must go without an adequate noonday meal at school, or perhaps an inadequate meal at home, or none at all” and blames “inadequate funding at federal, state and local levels with the end result that the children who cannot afford to pay are the losers.”

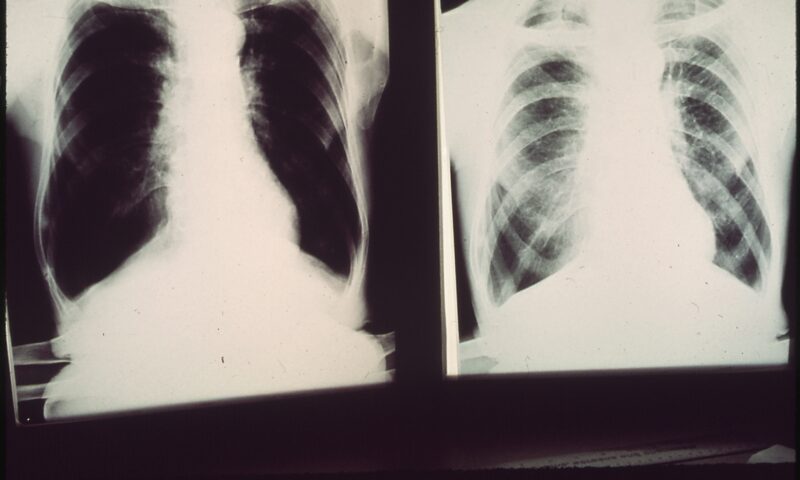

Also in 1968, a report called Hunger USA, by the Citizens’ Board of Inquiry into Hunger and Malnutrition in the United States, found widespread hunger throughout the country, and in May 1968, a television documentary on CBS called Hunger in America focused on American children dying of malnutrition.

One of the most touching scenes in this CBS documentary (which also appeared in the 2010 documentary Lunch Line) motivated the late Senator George McGovern (D-SD) to become a leader in the fight against hunger. The camera focused on a boy perhaps 10 years old, leaning against the wall of his school cafeteria watching the other students eat lunch; the interviewer asks the boy what he gets to eat at school, and the boy says, “Nothing.” When the interviewer asks the boy how he feels watching the others eat, he says he feels ashamed, and when asked why, the boy answers “I don’t have any money.”

Of that scene, McGovern later remarked, “I said to my family that was watching the documentary with me, “You know, it’s not that little boy who should be ashamed, it’s George McGovern, a United States Senator, a member on the Committee on Agriculture.””

By the end of 1969, politicians on both sides of the aisle embraced the idea that hunger could and should be eradicated in the United States. At the December 1969 White House Conference on Food, Nutrition and Health, President Richard Nixon made a “commitment to provide free or reduced-price lunches for every needy child in America.”

Senator McGovern established the Senate Select Committee on Nutrition and Human Needs and, along with his ally in the fight against hunger Senator Robert Dole (R-KS), and the other members of his committee (both Republicans and Democrats), was able to drive changes to the federal school meal programs including changing the funding from a block grant which was insufficient to feed the actual number of students in poverty, to a formula based on family income and applied uniformly across all school districts.

This change, which had the full support of the President, guaranteed government payment to school districts for every meal served to a qualifying student, and is the single most important factor driving the increase in the number of students eating free school lunch since 1969.

A report issued in 1970 to assess progress one year after the White House Conference on Food, Nutrition and Health, found that “from October 1968 to October 1970, the number of children receiving free or reduced-price meals more than doubled. This number will continue to grow through the school year. Free or reduced-price lunches should now be available to all eligible children in schools which participate in the School Lunch Program.”

In other words, more low income students eat free school meals now than in 1969 because now those meals are available to them, whereas before they weren’t.

It’s simply not true that, as Jeffrey would have us believe; parents of poor children in the late 1960s “would frequently visit grocery stores where they would use their own money to buy things like peanut butter and jelly, and bologna and cheese to make lunches for their kids to haul to school in brown paper bags.” The truth is that in the late 1960s, many children living in poverty went hungry at lunch time because their parents had no money for peanut butter or bologna, because their school didn’t have a lunch program, or because there wasn’t enough funding for their school to feed all its poor children.

The number of students eating free school meals has increased not because the poor have abdicated their responsibility to feed their own offspring, but rather because this country now recognizes – as it failed to do in the late 1960s – that poverty exists in America, that it leads to hunger and malnutrition, that hungry children can’t learn, and that the $3 daily cost of a government paid lunch is a pittance compared to what it costs to treat children for hunger-related medical conditions, or to provide extra tutoring to try to bring their academic achievement up to the level of their well-fed peers.

There’s a reason why Jeffrey chose 1969 as his comparison year – it’s because that was the year that President Richard Nixon created the Food and Nutrition Services (FNS) division of the USDA, which oversees school meals, and therefore the 1968-69 school year is the first for which that department provides data. The creation of FNS was one of many very deliberate actions, including the expansion of the Food Stamp program and the establishment of WIC [Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children], taken to combat a crisis of hunger and malnutrition in the U.S. of which the nation had only just become aware; children were literally dying of hunger right here in America, and the expansion of the school lunch program was intended to ensure that these children would receive at least one nutritious daily meal.

The very fact about which Jeffrey is complaining – that six times more kids now eat free school lunch than in 1969 – is proof that this initiative has been successful. More low income students are eating healthy and nutritious school meals today than ever before, and while feeding programs may be just a Band-Aid on the gaping wound of poverty, which do nothing to address poverty’s root causes, eliminating feeding programs would be rubbing dirt into that wound.

Would Jeffrey really prefer that we go back to the 1960s? Not the imaginary 1960s of his dreams, where poor parents went grocery shopping for peanut butter and bologna to make brown bag lunches for their children, but the actual 1960s of the documentary Hunger in America, with its horrifying images of children literally dying from malnutrition? Can any human being not be reduced to tears seeing a hungry 10 year old admit his shame at having no money while he watches his wealthier classmates eat their school lunch?

Like Holocaust deniers, moon-landing conspiracy theorists, those who wear tin foil hats to keep aliens from controlling their brains, and others who stubbornly cling to their own version of reality despite all evidence to the contrary, Jeffrey and his ilk apparently believe that simply by starving poor school children, this country will see its rate of babies born out of wedlock drop. I have just one question for anyone who thinks that the reason why unwed women bear children is so that they can scam a free school lunch: Can I sell you a tin foil hat?

(Dana Woldow has been a school food advocate since 2002 and shares what she has learned at PEACHSF.org. Her post first appeared on BeyondChron and is republished with permission.)

-

Latest NewsJune 17, 2025

Latest NewsJune 17, 2025A Coal Miner’s Daughter Takes on DOGE to Protect Miners’ Health

-

Beyond the BorderJune 10, 2025

Beyond the BorderJune 10, 2025Detained Man Says ICE Isn’t Treating His Colon Cancer

-

Column - State of InequalityJune 5, 2025

Column - State of InequalityJune 5, 2025Budget Cuts Threaten In-Home Assistance Workers and Medi-Cal Recipients

-

Column - State of InequalityJune 12, 2025

Column - State of InequalityJune 12, 2025‘Patients Will Suffer. Patients Will Die.’ Why California’s Rural Hospitals Are Flatlining.

-

Column - California UncoveredJune 18, 2025

Column - California UncoveredJune 18, 2025Can Gov. Gavin Newsom Make Californians Healthier?

-

Featured VideoJune 10, 2025

Featured VideoJune 10, 2025Police Violently Crack Down on L.A. Protests

-

Latest NewsJune 4, 2025

Latest NewsJune 4, 2025Grace Under Fire: Transgender Student Athlete AB Hernandez’s Winning Weekend

-

The SlickJune 6, 2025

The SlickJune 6, 2025Pennsylvania Has Failed Environmental Justice Communities for Years. A New Bill Could Change That.