As Anita Wolfe sat in the hallway of a Charleston, West Virginia, county courtroom, waiting to testify against the U.S. government, she thought of her dad, who first started working as a coal miner when he was around 12.

She remembered his wild stories about coal-loading contests and working as a mule boy. But she also remembered his death certificate, which listed black lung and silicosis, two pulmonary diseases related to dust in mines, as contributing factors.

Before she retired, Wolfe launched and ran a mobile clinic through the National Institute For Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) that screened miners at their mines and tried to catch lung diseases early.

Anita Wolfe speaks with Ray Anthony Bartley, a Kentucky coal miner with black lung disease, in 2019. Photo courtesy NIOSH.

In April, as part of the Trump administration’s Department of Government Efficiency initiative, around 90% of NIOSH staff received layoff notices. Many were placed on administrative leave — including the mobile clinic crew, workers who review miners’ test results and researchers trying to prevent these lung diseases in the first place.

Wolfe was in the courthouse to try to get those jobs back. Now, her mobile clinic workers are back, along with all the other workers in the institute’s Respiratory Health Division. But researchers elsewhere in NIOSH who also work on prevention are still slated to be laid off.

To Wolfe, that’s a problem. About a fifth of the coal miners in Central Appalachia have black lung, Wolfe said. And from 1970 to 2016, more than 75,000 died. Nationally, a 2023 NIOSH study found that coal miners are twice as likely to die of lung diseases than nonminers. Wolfe called black lung and silicosis “entirely preventable.”

“It comes down to how much is a life worth,” Wolfe said. “You want more coal, but you don’t care about the coal miners and what’s happening to them.”

* * *

For some coal miners, pausing the black lung programs at the National Institute For Occupational Safety and Health created an immediate problem, because without a stamp of approval from the institute, coal miners can’t access federal “Part 90” benefits that allow them to get reassigned to jobs with less dust exposure.

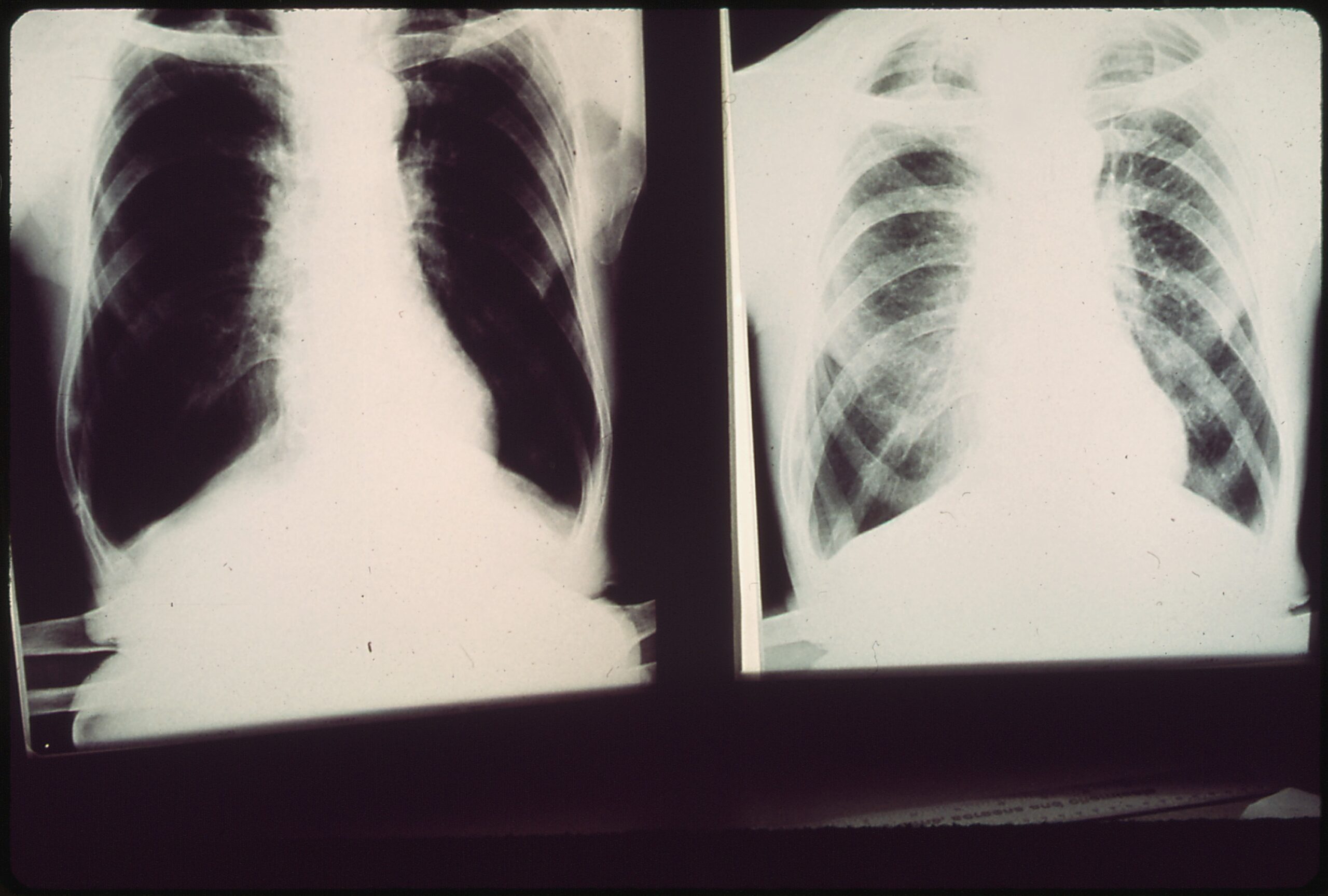

Black lung has no cure, but avoiding dust can stop the disease from getting worse. With the pause, X-rays and medical records now sat in folders, unexamined.

So Wolfe and others began campaigning, collaborating with public health workers and miners to try to get the NIOSH workers back. Wolfe enlisted the support of West Virginia Republican Sen. Shelley Capito, who successfully petitioned to get black lung workers off administrative leave in the short term. Still, that was just a temporary fix.

Sam Petsonk, a lawyer, and Harry Wiley, a coal miner, decided to sue the Department of Health and Human Services, which oversees NIOSH. “To me, he was very courageous for doing that,” Wolfe said of Wiley.

At trial, Wolfe and Wiley were both called to testify, and on May 7, they sat with other witnesses in the courthouse hallway. For hours, the group made small talk about kids and summer vacations, scrupulously following instructions to avoid any chatter about the department’s “reduction in force.”

Anita Wolfe as a child with her father, William Stockett. Photo courtesy Anita Wolfe.

One by one the witnesses entered the courtroom. Wolfe was last. “Everything was going through my head,” she said. She was nervous. But then, she remembered her dad. “I just felt like he was there with me, you know? Kinda egging me on, like, ‘You got this, baby girl.’”

When Wolfe took the stand, she was calm, and described the value of NIOSH’s programs. The defense, she said, “didn’t offer much defense at all.”

After the trial, Wolfe joined Wiley and Petsonk for sandwiches. “They seemed fairly confident that it was gonna be found in favor of the miner,” she said.

A few days later, the judge ruled in Wiley’s favor. Staff at the mobile clinic and the broader National Institute For Occupational Safety and Health Respiratory Health Division got their jobs back for now, although the program is still working to get back up and running. Staff at the institute’s National Personal Protective Technology Lab were also called back; they certify a variety of respirators that help keep miners and other workers safe.

But other institute researchers working to prevent mining-related lung diseases heard nothing.

While researchers in the Respiratory Health Division focus primarily on tracking disease and helping individual miners, researchers at NIOSH’s Pittsburgh and Spokane Mining Research Divisions focus on innovation, developing new tools to prevent disease in the first place.

The judge’s preliminary injunction said the law requires that kind of research. But the injunction did not explicitly put Pittsburgh and Spokane researchers back to work.

The Department of Health and Human Services did un-fire their boss, a statutorily required associate director overseeing the Office of Mine Safety and Health Research. But it did not bring back the hundreds of researchers who report to that administrator.

“He’s new. He hasn’t even met us yet!” said Cassandra Hoebbel, a NIOSH researcher in Pittsburgh and a union steward for the Association of Federal Government Employees.

“A lot of people contacted me and were like, ‘Oh my God, you got your job restored!’” she said. “It’s like, no they’ve only restored a tiny part of it.”

Hoebbel said that mine health and safety research at the institute has been mostly on pause since January due to the Trump administration’s restrictions on funding and travel. For almost five months, researchers have been unable to visit mines to measure dust levels, test new equipment or improve software tools.

That’s a long-term loss for miner health, but it’s a short-term loss as well: NIOSH field work often leads to quick-fix changes by the mine operators the researchers collaborate with. Now, those improvements aren’t happening. External grants for technology development and commercialization were also “terminated for convenience.”

That’s despite the fact that, after a long decline, lung diseases in miners are again on the rise: Black lung cases have been increasing for two decades, according to a 2018 NIOSH study, and severe cases have caught back up to their all-time high. And it’s not just black lung. A 2023 study found that coal miners are dying of a variety of lung diseases at higher rates than in the past. Some are also dying younger.

* * *

“It used to be that people said black lung was an old man’s disease, and that’s not true. We just buried a thirtysomething miner,” Wolfe said.

Many younger miners suffer from lung diseases caused not by coal dust but from quartz dust, officially called respirable crystalline silica. As coal deposits became tapped out, mines went after harder-to-reach coal, generating more quartz dust from the surrounding rock. Modern mining machines may also contribute to the dust.

Silica dust exposure is not unique to coal miners, who represent a small sliver of miners in the U.S. Silicosis is common in miners at all sorts of mines.

While coal workers are eligible for “Part 90” transfers and benefits based on dust exposure, those who mine for sand, rocks, precious metals and other material are not.

For all miners, silica dust protections are decades out of date. After Wolfe’s mobile clinics helped identify new clusters of lung disease, a 2014 rule lowered allowable limits for coal dust exposure. Similar standards lowered limits for silica dust in industries like construction.

The NIOSH mobile screening unit provides miners with free screenings for lung disease. Photo courtesy NIOSH.

But a rule to lower by half the silica dust exposure limit in mines stalled for a decade. The rule finally passed in 2024 — then a 2025 start date was postponed, after pushback from mine operators, who said implementation would be too difficult.

Mine operators objected to a final version of the rule that said it was not enough to implement a check list of “good enough” dust control measures, to give miners masks or to rotate them in and out of dusty areas to reduce their exposure. Instead, the final rule says mines need to actually reduce the hazardous dust.

The rule also mandates silicosis monitoring programs, similar to Wolfe’s black lung monitoring work, but for non-coal miners.

However, the same day President Donald Trump held a press conference promoting the “abandoned” coal industry, the Department of Labor postponed the rule’s upcoming start date for coal mines from April to August. (Stone mines still have until April 2026 to comply.)

Earlier this year, the Department of Labor announced plans to close 34 of the mine enforcement offices that work to hold mine operators accountable for the current silica dust standard. In late May, those plans were reversed.

* * *

Dust is a constant presence in mines, and it lurks in overlooked places. Currently paused National Institute For Occupational Safety and Health research has the potential to improve the dust problem.

Decades ago, government mine safety researchers identified controls that could be used to reduce dust in mines, such as improving ventilation.

But mines have been using those strategies for years, and lung diseases stubbornly persist.

Traditionally, mine inspectors check dust levels a few times a year to confirm compliance. But those checks don’t provide much actionable information about how to make things better. That’s frustrating for mines and for miners. So NIOSH has been working on ways to make dust easier to spot.

Their personal dust monitors already let miners view their own mine dust exposure in real time. Other projects are helping miners make sense of that kind of data.

In 2015, Hoebbel observed field work for an award-winning study by institute researcher Emily Haas that outfitted miners with both a dust monitor and a video camera and then compared the feeds to see why dust levels spiked.

“They had two guys walking side by side,” Hoebbel said. One of their dust monitors “kept going up, up, up — and the other guy was walking right next to him and his was fine.”

The researchers, curious, asked, “When’s the last time you washed your sweatshirt?” Hoebbel said. “He’s like, ‘Oh man, I can’t tell you the last time I washed this thing!’”

Before the study, the participating miners felt confident that wearing masks and following established procedures would keep them safe. Afterwards, they were full of questions about silica exposure. The mine in the study, for its part, replaced cloth vehicle seats and gloves with leather, which is easier to wipe clean.

But attaching monitors to miners, while good for sussing out dirty sweatshirts, is less effective for tracking dirty equipment or faulty ventilation, which may be getting dust on sweatshirts in the first place.

Coal miners in southern West Virginia pose for a picture before heading underground. Photo: Anita Wolfe.

So another institute project used air quality monitors to help mines and miners better understand sources of exposure within mines. In a recently published pilot study, weekly reports of real-time data helped staff at sand mine notice minute by minute shifts in dust at key locations.

As a result, the mine’s industrial hygienist turned some machines on before miners arrived for the day, so they wouldn’t be exposed to an extra burst of dust that spiked when machines were starting up.

A foreman also noticed a dust hot spot near a particular conveyor belt and used parts they had on hand to come up with a fix, reducing dust in the area threefold.

The approach is promising, and NIOSH has a history of creating useful gadgets for miners that are now widely used and often legally required. From October to January, those researchers made several site visits. Then, nothing.

That project is currently paused, along with much of NIOSH’s other research into silica exposure and impacts.

Many dust monitors test general dust levels; teasing out silica in particular means distinguishing one speck of dust from another. So researchers were working to make same-day infrared spectroscopy tests more accurate. Others were developing continuous, real-time silica monitoring tools.

Mining researchers were also collaborating with the NIOSH chemistry team to understand exposures to silica in nano-clay, or particles of clay minerals. But the institute’s analytical chemists are all still facing layoffs. So are the researchers trying to address all the other hazards miners face.

Federal mine safety and health research began in earnest in the 1910s, around the time Anita’s father was born. Back then, hundreds of coal miners died each year in mine explosions.

NIOSH and its predecessors made those incidents rare. But mine risks keep evolving: As mines age, for example, massive sinkholes can appear, and institute researchers have been helping mine operators predict them.

They are also studying ways to keep lithium batteries from exploding, working to understand if a growing number of natural gas wells could leak explosive methane into mines and devising ways to better prepare miners to survive accidents using virtual reality and to prevent accidents involving giant haul trucks.

All of that work is now on pause.

* * *

Wolfe hopes that the Department of Health and Human Services will restore NIOSH researchers voluntarily. A recent Health and Human Services draft budget for 2026 includes stable funding for mining research, even though researchers are not currently working.

In the meantime, the fate of their work could be determined by another court case, this one brought against the Trump administration by plaintiffs including Hoebbel’s union, the American Federation of Government Employees.

It’s among several lawsuits that allege that by cutting funding and staff without authorization, the administration’s DOGE initiative has usurped the powers of Congress.

Many institute layoffs were previously scheduled for June 2. But several days before, a judge issued an injunction putting the layoffs on pause until that case is adjudicated. The Trump administration has appealed that injunction to the U.S. Supreme Court.

At issue is whether Congress has the right to commit to generational goals, like the health of miners, that require stability as executives come and go.

For Wolfe, the answer is obvious. “I always tell people: ‘I’m not gonna argue with you about whether coal is good or bad. But as long as it’s mined and there are coal miners, we need to take care of them.’”

Coal Workers’ Health Surveillance Program and NIOSH stickers adorn a coal miner’s lunch box. Miners collect reflective stickers to put on their equipment. Photo: Anita Wolfe.

Copyright 2025 Capital & Main

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 22, 2026

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 22, 2026

The SlickJanuary 20, 2026

The SlickJanuary 20, 2026

Latest NewsJanuary 21, 2026

Latest NewsJanuary 21, 2026

Latest NewsJanuary 22, 2026

Latest NewsJanuary 22, 2026

The SlickJanuary 23, 2026

The SlickJanuary 23, 2026

The SlickJanuary 27, 2026

The SlickJanuary 27, 2026

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 29, 2026

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 29, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026