Education

Gap Co-Founder Doris Fisher Is Bankrolling the Charter School Agenda – And Pouring Dark Money Into CA Politics

Born Doris Feigenbaum in 1931 in New York, Fisher and her husband struck modern-day gold in San Francisco when they founded the first Gap store there in 1969. By all indications, Doris and her husband, who passed away in 2009, worked hand in hand building the brand — which, like many global retailers, has also faced intense scrutiny for its labor practices.

As co-founder of the Gap, San Francisco-based business leader and philanthropist Doris Fisher boasts a net worth of $2.6 billion, making her the country’s third richest self-made woman, according to Forbes. And she’s focused much of her wealth and resources on building charter schools. She and her late husband Donald donated more than $70 million to the Knowledge is Power Program (KIPP) and helped to personally build the operation into the largest network of charter schools in the country, with 200 schools serving 80,000 students in 20 states. Doris’ son John serves as the chairman of KIPP’s board of directors, and she sits on the board herself.

Doris’ passion for charter schools also fuels her political donations. While not as well-known as other deep-pocketed charter school advocates like Eli Broad and the Walton family (heirs to the Walmart fortune), Fisher and her family have quietly become among the largest political funders of charter school efforts in the country. Having contributed $5.6 million to state political campaigns since 2013, Fisher was recently listed as the second largest political donor in California by the Sacramento Bee – and nearly all of her money now goes to promoting pro-charter school candidates and organizations. While often labelled a Republican, she gives to Democrats and Republicans alike, just as long as they’re supportive of the charter school movement. According to campaign finance reports, so far this election cycle she’s spent more than $3.3 million on the political action committees of charter school advocacy groups EdVoice and the California Charter Schools Association (CCSA), as well as pro-charter candidates. (Christopher Nelson, managing director of the Fishers’ philanthropic organization, sits on the board of CCSA, which, along with EdVoice, declined to comment for this article.)

Fisher’s philanthropic and political efforts are not as straightforward as simply promoting education, however. Recent investigations have found that she’s used dark-money networks to funnel funds into California campaign initiatives that many say targeted teachers and undermined public education. It’s why many education activists worry about the impact her money is having on California politics – and on California schoolchildren.

Fisher’s decision to double down on charter school candidates and political action groups this election season comes at a time of increasing backlash against such schools, which operate largely independently of public school systems but still receive public funding. Last month, the American Civil Liberties Union of Southern California and Public Advocates reported that more than 250 California charter schools – more than one-fifth of the state’s total – violated state law by denying enrollment to low-performing and other potentially undesirable students (the report caused more than 50 of the schools to change or clarify admissions policies, leading the ACLU to remove them from its list). This came after a study of charter school discipline by the UCLA’s Center for Civil Rights Remedies in March that found that charters suspended African-American students and students with disabilities at higher rates than traditional schools. And last year, a report by the Center for Popular Democracy, the Alliance of Californians for Community Empowerment Institute and Public Advocates Inc. concluded that in California alone, charter school fraud and negligence had cost state taxpayers more than $81 million.

It’s why in the last couple months, both the NAACP’s national convention and the Black Lives Matter movement have called for a moratorium on charter school growth, noting that the privatization of the nation’s schools was a major social justice concern. As the NAACP noted in its resolution, which has to be formally approved by the NAACP’s national board, “…weak oversight of charter schools puts students and communities at risk of harm, public funds at risk of being wasted, and further erodes local control of public education.”

And even if some of the charter schools Fisher champions have been a success, she’s secretly supported efforts that critics regard as undermining the success of the public school system and teachers. A recent investigation by California Hedge Clippers, a coalition of community groups and unions, found that Fisher was one of a number of wealthy Californians who in 2012 used a dark money network involving out-of-state organizations linked to the conservative Koch brothers to shield their donations to controversial campaign efforts that year. The money was used to oppose Proposition 30, a tax on high-income Californians to fund public schools and public safety, and support Proposition 32, which, among other things, would have severely limited the ability of organized labor, including teachers unions, to raise money for state and local races.

At the time of the campaign, none of these donations were public. In fact, fellow charter-school advocate Eli Broad publically endorsed Proposition 30 while secretly donating $500,000 to the dark money fund dedicated to defeating it. And Fisher herself had close ties to Governor Jerry Brown, a key proponent of Proposition 30. Brown’s wife Anne Gust Brown worked as chief administrative officer at the Gap until 2005 and is credited with helping to improve the company’s labor standards, and the Fishers were major financial supporters of Brown’s 2014 campaign to pass Proposition 1, the water bond, and Proposition 2, the “rainy day budget” stabilization act.

“I would imagine that it caused some domestic strife,” says Karen Wolfe, a California parent and founder of PSconnect, a community group that advocates for traditional public schools. “[Anne likely] thought she had the Fishers’ support on her husband’s crowning achievement, a tax to finally balance California’s budget and bring the state out of functional bankruptcy. This was absolutely his highest priority.”

In total, according to the Hedge Clippers investigation, Fisher and her sons donated more than $18 million to the dark money group. It wasn’t the only time the Fisher family has worked with political organizations known for concealing their financial supporters. In 2006, current KIPP chairman John Fisher gave $85,000 to All Children Matter, a school-privatization political action group in Ohio that was slapped with a record-setting $5.2 million fine for illegally funneling contributions through out-of-state dark money networks. Instead of paying the fine, All Children Matter shut down and one of its conservative founders launched a new group: the Alliance for School Choice, which in 2011 listed John Fisher as its secretary. And last year, Doris Fisher contributed $750,000 to California Charter School Association Advocates, which funneled such donations to a local committee. The names of individual donors wouldn’t be disclosed until after the election.

Despite the dark money group’s best efforts, Proposition 30 passed and Proposition 32 failed. As a result, according to the Hedge Clippers report, KIPP schools in California that Fisher had long championed received nearly $5 million in Proposition 30 taxpayer funding in the 2013-2014 school year.

“What outrageous hypocrisy that she and her cabal profess to be all about the interests of quality education of low-income communities of color, and yet behind the scenes are undercutting one of the most important policies to fund public education we have seen in decades,” says Amy Schur, state campaign director for the Alliance of Californians for Community Empowerment, part of the Hedge Clipper coalition, which is advocating for the extension of the Proposition 30 tax at the ballot box this November.

To critics, such findings suggest that Fisher and other deep-pocketed advocates currently pumping millions into California politics to promote their charter-school agenda are ignoring the sorts of fundamental financial reforms that could make a difference for struggling schoolchildren but would hurt their bottom lines.

“These people are looking at inequality and saying, ‘These people do not have sufficient education,’ when there are other issues regarding the structure of the economy that would more directly impact the poor,” says Harold Meyerson, executive editor of the American Prospect. “It’s nice the Waltons and the Fisher family are concerned about the poor with regards to the quality of their education, but a more direct way to help them would be to give workers at Walmart and the Gap a raise and to give them more hours.”

Photo via Andybis123 via Wikimedia Commons

Born Doris Feigenbaum in 1931 in New York, Fisher and her husband struck modern-day gold in San Francisco when they founded the first Gap store there in 1969. By all indications, Doris and her husband, who passed away in 2009, worked hand in hand building the brand.

The result was a $16-billion business with more than 3,700 stores worldwide. While Gap Inc. recently received attention for being among the first major brands to voluntarily increase the minimum wage of its U.S. workforce, like many global retailers, it has also faced intense scrutiny for its labor practices, such as the poor working conditions of its factory workers overseas.

Even after the company released “Sourcing Principles and Guidelines” in response to such critiques in 1993, the company was publically cited for factory condition violations six times in the following 14 years. Indeed, just two years after the guidelines were issued, New York Times columnist Bob Herbert offered this withering observation:

“The hundreds of thousands of young (and mostly female) factory workers in Central America who earn next to nothing and often live in squalor have been an absolute boon to American clothing company executives like Donald G. Fisher, the chief executive of the Gap and Banana Republic empire, who lives in splendor and paid himself more than $2 million last year.”

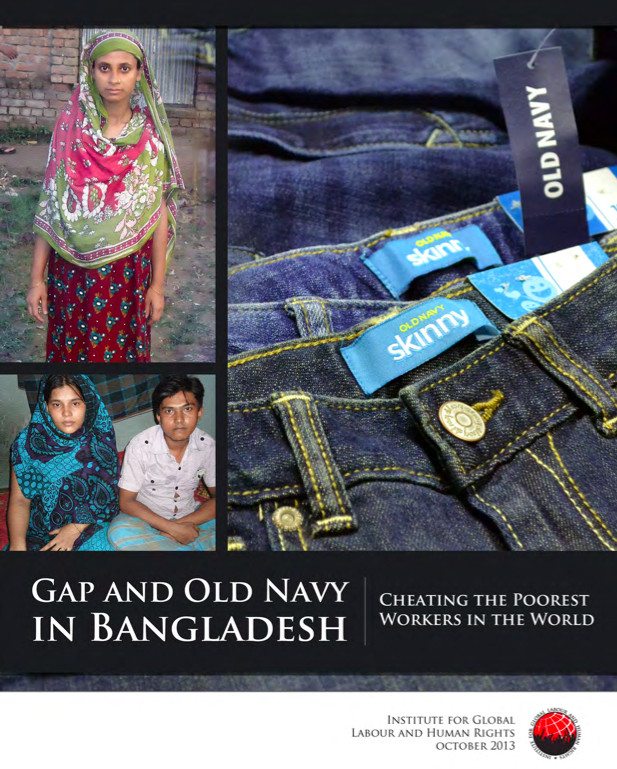

2013 report exposed abusive working conditions in a Bangladeshi factory that made clothes for The Gap.

Stung by the negative publicity, the Gap launched an effort to crack down on labor abuses that won widespread praise. But the problems did not go away. In 2007, the Gap found itself embroiled in a child labor controversy after the British paper The Observer reported that children as young as 10 were working for up to 16 hours a day to make clothes, including items with Gap labels. To contain the damage, the company announced a set of measures to eliminate the use of child labor. But in 2013, The Gap once again made headlines — this time for selling clothes manufactured in a Bangladesh sweatshop where workers were allegedly made to work 100 hours per week and cheated on wages that averaged 20 to 24 cents per hour.

The Fishers’ experiences with the Gap may well have shaped their involvement in education reform, which began in 2000 when they learned about Mike Feinberg and Dave Levin. The two Teach for America alums had launched the first two KIPP charter schools, one in Houston and one in the South Bronx, designed around high expectations, extended school days and performance-driven results. “[The Fishers] liked the notion that careful training and well-constructed, on-the-job experience, as they had done in their company, could produce better school leaders,” says Washington Post education writer Jay Mathews, author of a book on KIPP, Work Hard. Be Nice.

And it’s why when Scott Hamilton, the charter school expert the couple had hired to find education projects, suggested they work to scale up Feinberg and Levin’s program, they agreed, spending $15 million to create the KIPP Foundation to train people on how to launch new KIPP schools. Soon KIPP was spreading across the country the way Gap stores did in malls from coast to coast. Along with donating more money to KIPP, the Fishers also gave money to Teach for America, which became a major source of KIPP’s teachers. “[Don] used what he learned in growing Gap Inc. to show us what we could do in public education, and tens of thousands of children have benefited from his commitment and generosity,” notes KIPP Foundation CEO Richard Barth in Donald Fisher’s Gap biography.

KIPP is considered by many experts to be a success story. “You can make good arguments that many charters are disappointing, but not KIPP,” says Matthews. “It is the most studied charter school system by far, and all of those independent studies, particularly a big one by Mathematica, show that KIPP raises achievement significantly higher than regular schools for similar kids in similar neighborhoods, even in a randomized study.”

But not everyone is thrilled by KIPP’s approach. In 2012, a study led by Julian Vasquez Heilig, then faculty in the University of Texas at Austin College of Education’s Department of Educational Administration, found that despite KIPP’s claims that 88 to 90 percent of their students went to college, black high school students were much more likely to leave KIPP and other urban charter schools in Texas than they were to leave traditional urban public schools. And in New York City, the other place where KIPP got its start, math teacher and education blogger Gary Rubinstein found that in 2012-2013, the three KIPP schools that have kindergartens posted lower 3rd grade test scores than two-thirds of the other charter schools in the city. And despite KIPP’s public standing, it’s not always transparent about its operations. Earlier this year the Center for Media and Democracy found that the organization claimed information about its graduation and matriculation rates, student performance results and how it would spend taxpayer dollars was “proprietary,” leading the U.S. Department of Education to redact this information from KIPP application documents before they were released to the public.

KIPP has also been criticized for its schools’ tendency to “churn and burn” young teachers because of long, demanding workdays (a third of KIPP teachers left their jobs in the 2012-2013 school year). Similarly, Teach for America, which funnels many of its teachers to KIPP schools, has faced increasing scrutiny for supplanting qualified teaching veterans with poorly trained replacements in struggling communities that are most in need of qualified instructors.

Some critics wonder if the Fishers’ background is in part responsible for such circumstances.

“If you look at the industries where these people made their wealth, you can see why they have this idea that you have to squeeze labor to make your profits,” says Cynthia Liu, founder of K-12 News Network and a charter school critic. “If you have children in India making your clothing, your profit margin is very large. Similarly, if you use automation and low-cost education ‘shock troops’ to minimize the role of teachers, making them the ‘guide on the side rather than the sage on the stage,’ you minimize your education labor costs.”

The result, says Liu, isn’t just poorly trained and overworked teachers, it’s undervalued students. “When charters rely on the churn of an expendable, fungible teaching workforce using scripted curriculum instead of career and authentically-credentialed teachers, it cheapens the learning experience for students and the profession,” she says. “A child’s education isn’t a five dollar T-shirt, it’s an investment in our future collective well-being.”

-

Latest NewsJanuary 8, 2026

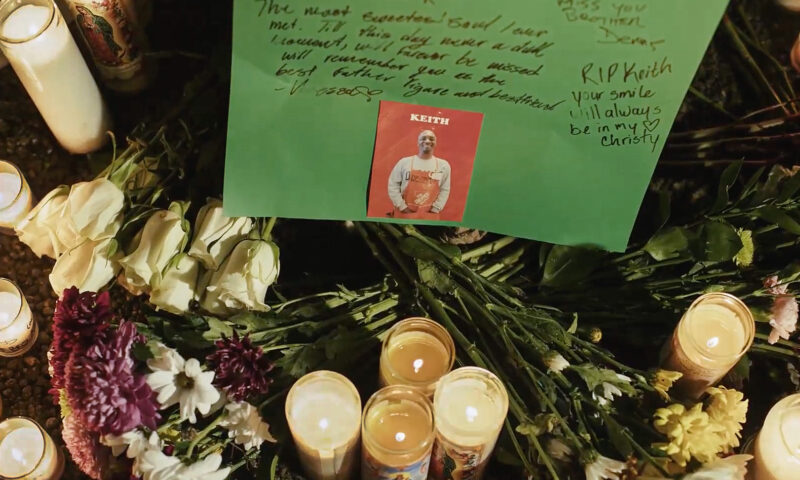

Latest NewsJanuary 8, 2026Why No Charges? Friends, Family of Man Killed by Off-Duty ICE Officer Ask After New Year’s Eve Shooting.

-

Latest NewsDecember 29, 2025

Latest NewsDecember 29, 2025Editor’s Picks: Capital & Main’s Standout Stories of 2025

-

Latest NewsDecember 30, 2025

Latest NewsDecember 30, 2025From Fire to ICE: The Year in Video

-

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 1, 2026

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 1, 2026Still the Golden State?

-

The SlickJanuary 12, 2026

The SlickJanuary 12, 2026Will an Old Pennsylvania Coal Town Get a Reboot From AI?

-

Pain & ProfitJanuary 7, 2026

Pain & ProfitJanuary 7, 2026Trump’s Biggest Inaugural Donor Benefits from Policy Changes That Raise Worker Safety Concerns

-

Latest NewsJanuary 6, 2026

Latest NewsJanuary 6, 2026In a Time of Extreme Peril, Burmese Journalists Tell Stories From the Shadows

-

Latest NewsJanuary 13, 2026

Latest NewsJanuary 13, 2026Straight Out of Project 2025: Trump’s Immigration Plan Was Clear