Labor & Economy

Couch Surfers and Billionaires: On the Sharing Economy

There has been no shortage of ink spilled on the so-called “sharing economy”. To cut through the rhetoric, LAANE’s Jon Zerolnick spoke with Tom Slee, an Ontario-based writer whose work on the intersection of technology, politics, and economics has appeared in The Literary Review of Canada, The New Inquiry, The Guardian, and Jacobin.

Let’s start with some definitions. What is the sharing economy?

Let’s start with some definitions. What is the sharing economy?

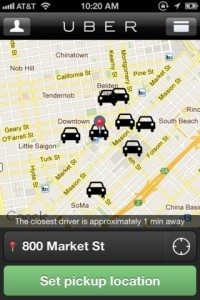

The sharing economy is internet platforms, and more-or-less independent people exchanging real-world goods and services through those platforms. This doesn’t necessarily have anything to do with sharing, but that is the name now.

Some of these platforms started off non-commercial. I’m thinking of things like Couch Surfing, where individuals host each other in their own homes, with no money exchanged; it was a non-profit and provided a coordination service. Then people started saying, “Well, I can share, but I can take a bit of money, too.” So then we end up with Airbnb, and now we really have the whole spectrum, Couch Surfing on one end, and on the other end Uber, the taxi competitor, which has never described itself as part of the sharing economy.

How did you get interested in these sorts of operations?

I’m involved in digital technology, but over the last few years, people – especially Silicon Valley companies – have taken a lot of the democratizing and egalitarian rhetoric around the internet – the rhetoric of openness – and they’ve used that to make money. What annoyed me about that is the betrayal: you’re taking language that I sympathize with, that I identify with, and you’re using it to make a big pile of money.

For instance, Airbnb just closed a funding round for $450 million. On paper, the founders will now be billionaires. And yet they’re using the language of community and the language of sharing. While the sharing economy presents itself as a communitarian movement, the venture capital-funded wing of it is an extension of the harshest of free-market economics into areas of our life that have previously been protected from it.

So who benefits and how?

The people who will do quite well off the sharing economy as it is evolving are consumers. Airbnb is a perfectly fine thing for travelers, and I wouldn’t be surprised if Uber and Lyft managed to offer reasonably good services most of the time. These things naturally work to do low-price, widely-available services, and might well work for consumers in the same way that Wal-Mart offers good things for consumers. They all offer low price, but what’s the cost of that?

Airbnb’s founders, “sharing economy” billionaires.

The biggest [benefits are] going to those who own the platforms. Airbnb now has the biggest valuation of sharing economy companies at $10 billion. The founders own about a third of that, so they’re doing well. Venture capital – those who have invested and bought part ownership of these companies – is going to do very well.

As you note, these practices have been around forever. What’s different about what’s going on now?

With the models that are being pushed now, there’s an opportunity for one company to become a global provider, and that’s where the interest of capital comes in. Airbnb can now be the place to go around the world. There’s a reason that Uber is opening up in country after country. This global ambition is what’s different now.

One potential upside is efficiency: that simple top-level matching that internet platforms do well. However, power inevitably accrues to the owner of the platform. They become influential, and they become able to challenge democratically-made laws and regulations, not only in their home countries, but around the world. And they’re unaccountable.

How do these companies impact standards for workers in the “regular” economy?

If you think of Airbnb as a hospitality company, the costs of running its operation are going to be a lot lower than traditional companies, because they offload a lot of those costs on the people whose apartments are being used. It does drive down the price. If you’ve been trying to make a living at a hotel, then this becomes problematic.

I think the taxi industry is one of the clearest examples. You have [taxi drivers] who are trying to earn a living, and then you have other people who are saying, “Well, I can take a bit less, because I don’t need to earn my whole living at it,” so it puts downward pressure on prices.

Delivery services are vulnerable. Walgreens made an agreement with Task Rabbit to do deliveries as a way of contracting out to even cheaper labor than they have already. So you have a temporary labor force with no rights.

To the extent that these platforms compete with [traditional] ways of offering services, it’s going to be very bad for salaries.

What about standards for the people in the sharing economy?

Uber drivers in the Bay Area and Seattle are now exploring unionization, because they have no protection. All the risk is being pushed down the chain to them. People are going to be increasingly vulnerable. This is probably the single biggest problem.

One other thing that bothers me is a rhetoric the companies all use around the idea of “extra money.” As in, “it’s not a job, it’s just a bit of extra money.” Once you say “extra money,” it’s like, “Oh, we don’t need rules and regulations, because it’s just extra money.” This is the same rhetoric that was used back in the 60s around women’s jobs. There wasn’t equal pay for equal work, because “it’s not a real job, it’s just extra money.” Using the phrase “extra money” is a slippery way to undermine employment standards, and to undermine things that unions and progressive politicians have fought for for a long time. Any low-paying job is a way to earn “extra money.” There’s no such thing as “extra money.”

What about government regulations that protect consumers and taxpayers?

We all have multiple roles that we play in society: we’re all consumers, we’re all workers, and we’re all citizens. The area that’s going to get most hammered here is our role as citizens.

There is a reason that city after city has some regulation around rental accommodations and tourism, and there’s not one big cartel around the world that’s organized that. Each city makes its own rules, and they differ from place to place. But everyone has found it necessary to have some rules: you have to balance out the market exchange side from the citizenship side.

You have the tax issue that’s being fought at the moment with Airbnb, you have the zoning question, you have landlord-tenant issues, there may be housing co-op agreements. You have all of these questions around what happens to the place where you live, and how it affects the rest of the community. Airbnb is trying to push aside as many of those questions as possible and focus only on the exchange, the market side of this. The danger is what happens to the rest of those concerns, and our role as citizens.

This is local democracy that is being challenged. In Seattle, sharing economy companies are funding an effort to repeal recent regulations. When you have this cynical voice from Silicon Valley saying “Oh, City Hall is corrupt” – which is what they end up saying – that’s an anti-democratic position they’re pushing. They are undermining democracy. There needs to be a lot of pushback on that.

Is there a way to achieve the communitarian benefits without the social costs?

I think there is. It comes down to two things. One is that venture capital is a real problem for the sharing economy. Once you’ve got large-scale capital involved, you have incentives that lead to problems. Venture capital demands a return, right? That means growth becomes the number one priority. And the demand for growth works against a number of the ideals that are used to promote [the sector]. Let’s take the idea that the sharing economy is sustainable, which has a big appeal to a lot of people in the green movements: sharing rather than buying, that’s a good thing. But that’s not how it works once you get into the venture capital mode.

To take an example, Zip Car was an early internet car sharing company. Then Zip Car got sold to Avis, and their goal, all of a sudden, is growth. So what do they end up doing? They go to university students and say “You don’t qualify to buy a car on your own, but you can access a car through us, because you can share it with other people.” Instead of being an alternative to owning, the venture capital people turn the service into a gateway drug to consumption. The goal of Zip Car is to get more cars on the road, as long as they’re Zip Cars. The goal of all of these entities is to grow the number of transactions, and all other considerations get pushed aside.

And two, micro-entrepreneurialism is a problem. That’s the Silicon Valley sharing economy phrase of the day: “You can make a living at this, you can make money from this.”

There’s a lot of ride-sharing services around, and probably the best one is the French outfit called BlaBlaCar. This is mainly people driving from city to city, not intra-city taxi services. It’s spreading throughout Europe. All you can charge for the journey is less than the cost of the journey. Now you don’t have the regulatory problems, because no one is making money off this, they’re just defraying costs. You don’t have the taxation problems. You avoid all of this. The BlaBlaCar example shows that you can do something useful as long as, yes, there’s money being exchanged, but no one is making money.

Note: All links have been added by C&M.

-

Latest NewsApril 8, 2024

Latest NewsApril 8, 2024Report: Banks Should Set Stricter Climate Goals for Agriculture Clients

-

Latest NewsApril 22, 2024

Latest NewsApril 22, 2024Oil Companies Must Set Aside More Money to Plug Wells, a New Rule Says. But It Won’t Be Enough.

-

Striking BackMarch 25, 2024

Striking BackMarch 25, 2024Unionizing Planned Parenthood

-

California UncoveredApril 9, 2024

California UncoveredApril 9, 2024700,000 Undocumented Californians Recently Became Eligible for Medi-Cal. Many May Be Afraid to Sign Up.

-

Feet to the FireApril 22, 2024

Feet to the FireApril 22, 2024Regional U.S. Banks Sharply Expand Lending to Oil and Gas Projects

-

Class WarMarch 26, 2024

Class WarMarch 26, 2024‘They Don’t Want to Teach Black History’

-

Latest NewsApril 10, 2024

Latest NewsApril 10, 2024The Transatlantic Battle to Stop Methane Gas Exports From South Texas

-

Latest NewsMarch 27, 2024

Latest NewsMarch 27, 2024Street Artists Say Graffiti on Abandoned L.A. High-Rises Is Disruptive, Divisive Art